This tightly focused, exquisite installation of Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes’s masterful series of late aquatint etchings, on view in a gem of a show at The Arthur Ross Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania through January 7, offers a rare opportunity to experience firsthand the work of a brilliant artist at the height of his powers. The show includes 38 first edition prints from The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra) and the Follies or Proverbs (Los Disparates or Los Proverbios). Unfortunately , this work is especially relevant right now because of the current wars in Ukraine and Gaza that seem to echo those that Goya lived through. I confess I was hard-pressed, while viewing works such as “A Heroic Feat! With Dead Men!” that depicts the naked and dismembered bodies of several men hanging on a tree, not to see them as mirror images of similar atrocities revealed in the press this past week regarding the rape, torture, and mutilation of Israeli women by Hamas soldiers on October 7 (not to confuse Hamas here with the majority of Palestinian citizens, also victims of the war). Looking at this work confirms Goya’s kindred sensibility regarding the quotidian experience of war, its specific and yet universal horrors. But what sets Goya’s images apart is not his ostensible subject of war but rather his unflinching insistence on feeling – the primary and deepest aspect of the human condition – as content.

Goya (1746-1828) is often seen as a bridge between the Old Masters and the early Modernists. One can see echoes of Rembrandt’s Biblical scenes in Goya’s strategic use of darks and lights, now mutated from Christian spirituality to suggest Enlightenment reason; in his succinct yet emotionally descriptive lines, so like those in Rembrandt’s spontaneously etched sketches (e.g., “Beggar Leaning on a Stick, Facing Left” (1630) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art); and most movingly in Goya’s haunting depictions of the foibles of human nature that we also find in Rembrandt’s late self-portraits, which Goya takes to the utmost limit in his late Black Paintings, specifically his vision of “Saturn Devouring His Son” (not in this show).

Similarly, we can trace Goya’s influence on later painters: in the romanticism of Delacroix, for example, and especially in Van Gogh’s quest to create “authentic” images born of his experiential understanding of the human condition. In fact, I couldn’t help but see in Goya’s painting “Courtyard with Lunatics” from 1794 (not in the show) a possible precedent for Van Gogh’s painting “Prisoners Exercising” (1890). Both artists depict captivity, but Goya emphasizes Enlightenment values in the men’s individuality and in the open-air setting centered in light, suggesting hope, while Van Gogh creates an infinity loop of indistinguishable men (save for a possible self-portrait) set in a bricked-up prison courtyard where the only light comes from a claustrophobic garish yellow.

Goya is indeed “modern” in this way that he prioritizes feeling as content. One can trace a line from his work that leads through Romanticism even further, inevitably to the Abstract Expressionists, who dispensed with representation altogether and ensconced feeling in gesture. Goya’s work, like theirs, is really about a visceral exploration of the existential conditions of our being. In the context of the current world, we could surely use a more robust awareness and examination of our shared humanity.

Although Goya’s roots were in the Enlightenment, he believed that Art was the product of both reason and imagination, a view that distinguished him from the Neoclassical painters. In 1799, he produced perhaps his most famous etching, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” (not in the show) in a portfolio of prints known as Los Caprichos (Caprices). This image shows a man asleep at his desk – perhaps Goya himself – while fantastical and threatening animals are splayed out behind him. In addition to the title, which he placed on the desk in the image, Goya also wrote a caption that reads, “Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she [imagination] is the mother of the arts and source of their wonders*.” However, by the time of The Disasters of War, roughly 1810-1820, Goya had lived through Napoleon’s invasion of Spain, a long and very bloody war, while serving as court artist to Napoleon’s brother Joseph, the usurper ruler of Spain. Whatever Enlightenment ideals about the nature of man that had previously burned inside him were long extinguished.

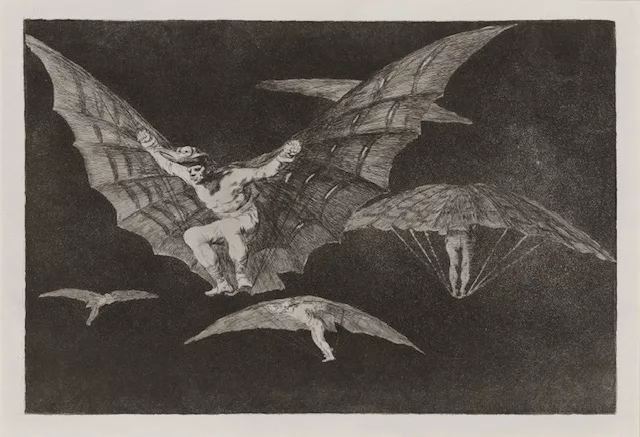

Plate 39 from the series Desastres de la Guerra (Disasters of War)

1810-1814, published 1863, Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased with the SmithKline Beckman Corporation Fund, 1949

Goya’s last portfolio of prints, created from 1815-1823, reflects his increasing anxiety and doubt about the fate of the imagination in the face of diminishing reason. This doubt is most pronounced in the Follies or Proverbs, sometimes called Dreams, and with good reason. In these hallucinogenic nightmarish images, the premise of the carnival – a reversal of the usual norms of society that seeks to subvert authority – is the only logic offered. Many of the Follies images, such as “Disorderly Folly,” depict animals, sometimes as people, sometimes as hybrid man/beast characters, and often with a frighteningly overt sexuality. These strange and grotesque images vacillate uneasily between a dark, black humor and outright terror; their visual language is that of the nightmare, the insane asylum, and hell.

Yet early twentieth-century Surrealists, living under similar circumstances of war as well as rapid industrialization spawned by the Enlightenment, saw in these images not terror but a fecund template for unleashing the freedom of the unconscious.

Goya: Prints from the Arthur Ross Collection, Arthur Ross Gallery, through Jan. 7, 2024. University of Pennsylvania (Housed in the Fisher Fine Arts Library Building), 220 South 34th Street Philadelphia, PA 19104.

End Notes

* Sarah C. Schaefer, “Francisco Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed January 3, 2024.

[For further reading about Goya on Artblog, we recommend Roberta’s 2004 report on a book talk by Robert Hughes about his then-new biography, “Goya.”]