On Thursday evening, January 18, the Barnes Foundation’s exhibition, Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, culminated with a fitting performance by Headlong Dance Theater. In “Horse Woman: Making a World of One’s Own,” dancers Courtney Henry, Saturn Freeman and Jungwoong Kim wound their way through the galleries and the open space of the Annenberg Court in a manner that was both ethereally beautiful and mildly disturbing, aptly mirroring the work of the hard-to-categorize French painter.

Although Marie Laurencin (1883–1956) might have been, as the Barnes’ press release states, “a fixture of the contemporary art scene in prewar Paris,” it has been more than thirty years since there has been a monographic exhibition of her work in the U.S. on this scale. Curators Simonetta Fraquelli and Cindy Kang put together an expansive survey, borrowing pieces from institutions ranging from the Metropolitan Museum in New York to the Centre Pompidou in Paris to the Marie Laurencin Museum in Tokyo.

The Barnes has embarked upon several interdisciplinary art initiatives recently, and combining dance with the visual arts is one of their approaches. This past summer, Brendan Fernandes’ dance piece, “Returning to Before,” was performed as a response to the exhibition, William Edmondson — A Monumental Vision. Unlike the Edmondson show, however, which was essentially mounted in one large gallery, Laurencin’s paintings were distributed throughout a series of interconnected, smaller spaces. This posed a particular challenge for Headlong’s choreographers, David Brick and Norma Porter. Their solution was to have both the individual dancers, or the trio together, wander through the exhibition, rather than present a focused performance.

Brick, who founded Headlong in 1993 along with Andrew Simonet and Amy Smith, put it this way during a panel discussion held in conjunction with the performance, “We developed the work to fit into the museum as a museum functions. We made the work so that as people were visiting the museum they could come across a thing that was happening and never think about it again, or they could follow a dance, and see another dance, see another dance . . .” Just the way viewers look at paintings or sculptures.

This approach worked well, allowing the dancers to respond not only to the physical spaces and the museum goers, but to the artworks on the wall. It also amplified details in Laurencin’s imagery that might have gone unnoticed. In addition, the costumes designed by Maiko Matsushima allowed the dancers’ bodies to mimic both the angularity and gracefulness of the bodies in the paintings, and to enter Laurencin’s private world of “dissolved boundaries” — between human and animal, and between male and female, what Brick calls a space “slyly apart from the approved social mores of the time.”

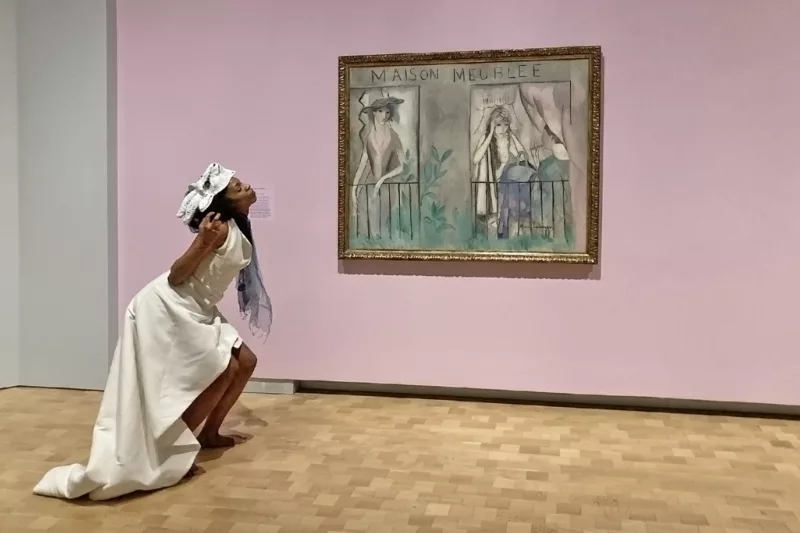

Look at the relationship between Courtney Henry’s gesture and Laurencin’s “The Woman-Horse” (1918) behind her. (Interestingly, no horse appears in the composition, only a gray dog and a pair of blue birds.)

Or notice the Barnes gallery railing, emphasized by Henry’s outstretched arm, and “Spanish Dancers/Danseuses Espagnoles” (1920).

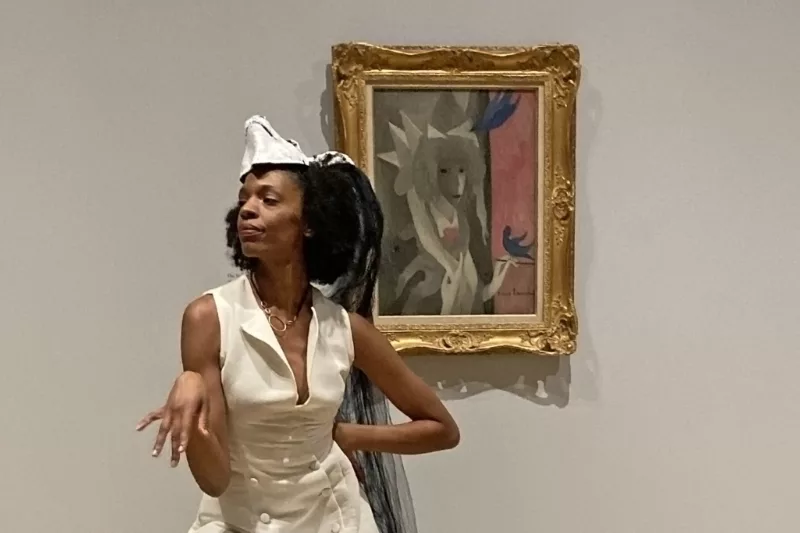

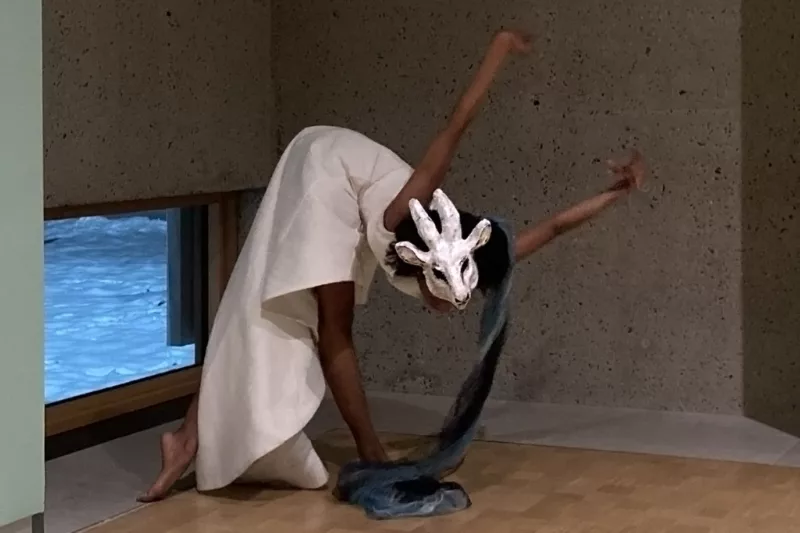

And what type of mammalian hybrid is this? A doe, a deer, a female deer?

The conversation between Headlong and Laurencin mirrors the painter’s own collaboration with dancers. In the 1920s, she was commissioned by Serge Diaghilev to design the sets, curtain and costumes for a Ballets Russes production featuring music by Francis Poulenc and choreography by Bronislava Nijinsky. The title, Les Biches, has multiple meanings; besides a female deer, it can refer to a “kept” young woman or a lesbian. Her curtain design depicts an alternate universe of hybrid beings. In this dance, Henry’s pose evokes similar ambiguity and chaotic movement.

What made this performance successful was a collaborative process that literally reached back through time. As Norma Porter said, it was a “wonderful opportunity to work collaboratively,” not only with the performers and designers, but with the paintings themselves. Maiko Matsushima concurred, noting that being “with the work” was an “amazing starting point.”

Headlong began by approaching Marie Laurencin and politely asking her to dance. Apparently, Marie said yes. Jordan McCree was ready to provide the sound, and the entire company enthusiastically joined in.

[Artblog interviewed David Brick and Andrew Simonet of Headlong Dance Theater for an Artblog Radio podcast in 2012. Listen here.]

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, The Barnes Foundation from Oct. 22, 2023 – Jan. 21, 2024.

Headlong Dance Theater’s performance “Horse Woman: Making a World of One’s Own” occurred on Jan. 18, 2024. Additional images at @headlongphilly.