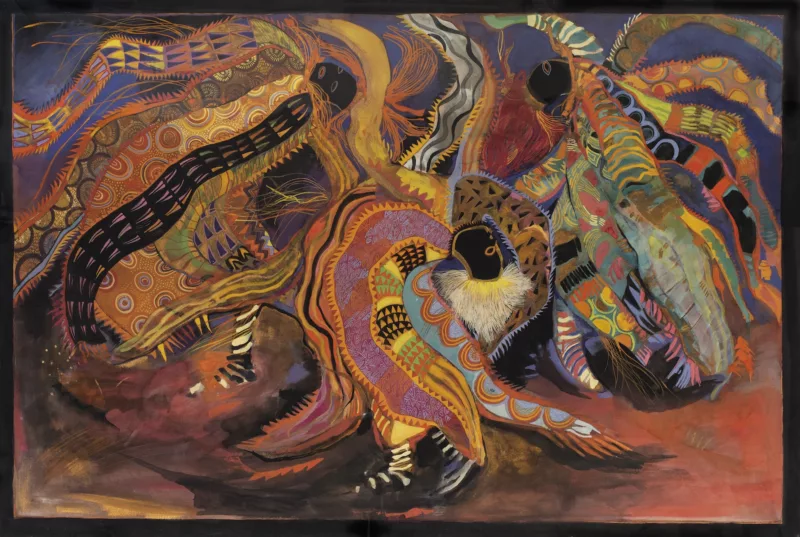

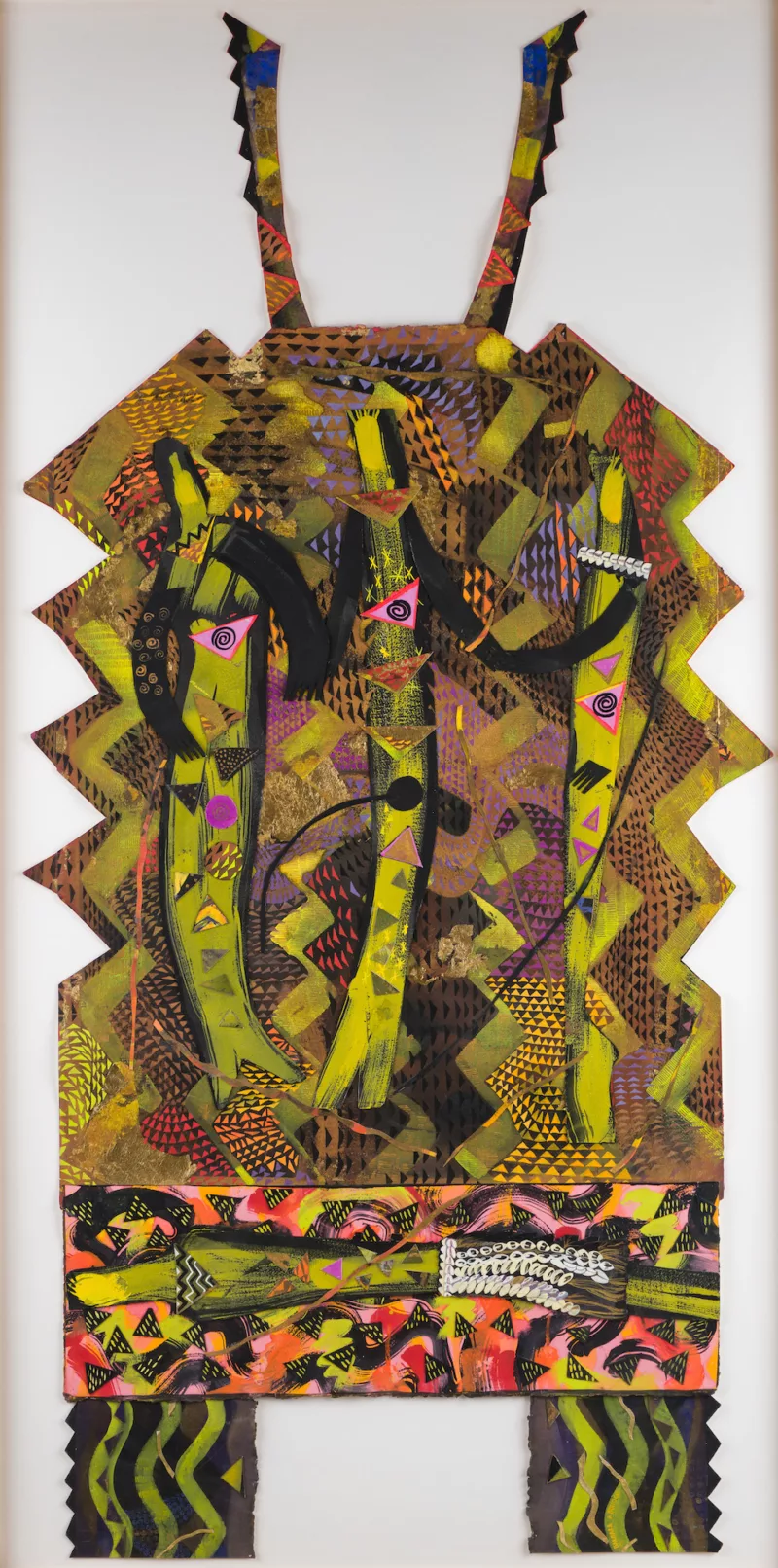

Like many in the Philadelphia art community, I have been an admirer of Barbara Bullock and her work for a long time. Back in 2006, Libby Rosof and I visited Barbara’s studio. We invited ourselves, and Barbara graciously welcomed us. We were curating a show of contemporary Philadelphia art for a small gallery outside of Washington, D.C., H&F Fine Arts, and we knew we wanted Barbara in the show. Barbara’s art is unique, beautiful, generous and focused on the Black experience. In a show with other Philadelphia voices, Barbara’s virtuosic cut paper construction, from the “Chasing After Spirits” series, stood out. It was the star of a star-studded show that also included Nick Lenker, Jayson Musson, Zoe Strauss, Candy Depew, Kip Deeds, Thom Lessner and Jen Packer.

I re-visited Barbara last January, 2023, at her studio in Germantown. It was, as I knew it would be, a tremendous visit, in which she told me more about her art, her journey, her connections to friends and community, her traveling, and the music and dance that are very present for her and present in her art. Black music. Black musicians. African dance. Barbara knew the dancers. And she knew many of the musicians. Barbara is an elder in the Philadelphia arts community. And while she looks back at her life and times, she is always grounded in the present and hopeful for the future.

Below are excerpts from last January’s sprawling conversation, edited for clarity and length. I’ve put links to more information and reviews of Barbara’s works at the bottom.

Music on her mind

Barbara was friends with Sun Ra, John Gilmore and Marshall Allen of the Arkestra. They used to visit her at her home studio in Germantown. She remembers attending a concert of theirs at McGonagle Hall on the Temple University campus.

“Everyone was seated, and there were no seats left, and we went and sat on the floor in the front. And the next thing, you could hear the drummers. And Sun and his entire Arkestra coming in, walking in procession, coming in procession. And the dancer was in front of them, and she was…it was like an Egyptian thing. And it was awesome. It was. I think he had seven or eight drummers. Wow. It was just powerful.”

Artists and hometown love equates to play for free or make art for free

“I remember John (Gilmore) said, ‘When we were in Philadelphia, they wanted us to perform free.’” He said, ‘When we were in Europe, a thousand people met us at the plane, at the airport.’”

It was very different in Philadelphia. Why? Barbara thought, then said, “Home. hometown. I think it’s hometown. It’s not ownership, but family. Mm-Hmm. You know?” She said it was the same “hometown” philosophy that made people in Philadelphia ask artists to work for free, or to sell their work with a “hometown” discount.

Sun Ra’s Arkestra visits

“Yeah.They would always come to visit me. Oh, it was nice. It was sort of like we were all artists…I think that we all began to communicate with each other.

“When most of the group came to visit me, and they’re standing outside my door and they’re chanting, ‘Barbara, Space is the Place! Let us in! Spaces is the Place.’ And I’m like, ‘I’m not opening the door until you promise me that you will not say that again.’ And they’re like, ‘We promise.’ So I would open the door, they were coming in, and of course they would say ‘Space is the Place.’ I was like, ‘Okay, I’m not getting that yet. I don’t know.’” (Laughs)

Dancing in the Art Department at Ile Ife, a Model Cities “Mecca”

Barbara loved to dance. And she did dance, with the dancers at Arthur Hall’s Ile Ife Center (now, the Village of Arts and Humanities) sometimes, but as head of the Art Department too, she had much to do. And that became a friction, a friction in what she calls the “Mecca” that was Ile Ife under the Federal Model Cities Program in the early 1970s.

Visit to Haiti with the Arthur Hall dancers

While at Ile Ife, Barbara visited Haiti with the Arthur Hall dancers and got to experience the culture and people and was drawn to the children. “I felt like meeting the children. They were really children. I mean, there was poverty, but they were really children. They weren’t hip like the children here, you know, like the guys who, as soon as their kid can can walk, they get ’em running shoes. You know what I mean?”

She went out to paint once in Haiti and didn’t realize she had set up her paints in a restricted area. “I set up all my painting materials and everything and I’m going to paint. And I had a rifle pointed at me. Wow. A soldier. A soldier in a uniform. He said, ‘You cannot be here.’ He was angry. And I didn’t know that you weren’t allowed to be where I was, and I just collected my things and got up and walked away. But the thing is, Haiti’s beautiful.”

Being called a Philadelphia artist

“Philadelphia is, I don’t know, it’s just home. I always say I’d like to be known as a Philadelphia artist…I’m not a Germantown artist, I’m a Philadelphia artist.”

Covid and the importance of work

Barbara’s brother died during Covid. He lived in Pottstown,PA, and she couldn’t go see him in the hospital and couldn’t go to the funeral because of Covid restrictions. Her cat, Molly, 18 years old, also died during the pandemic. And she cried and cried for the cat, for her brother. And she couldn’t focus on her work.

“I couldn’t do anything. I’m not feeling this. And, and that’s not like me. I mean, my parents are passed. You go through that and you still work. But I couldn’t. And I started thinking like, God, you know, like legacy…It’s for my family, it’s my legacy. I started [researching] on the YouTube. I started looking at Betty Saar’s work. Talking to Martha Jackson. We would talk, and I would look at other artists and I thought about Charles Searles, and I said, God.

“Most of the people that I came through with in the beginning were all fellows. They were all male. That was the era. It was like, these guys, regardless of what was going on with their families, they were working.

She said, “I don’t want to be like that, but I’m going to be like that. I’m going to work. You know. I’m not going to not work. I’m not going to stop. I know a few artists that did. I felt like you have to find another way. And maybe that’s what it was also going to be about.”

After all the thinking about her legacy and doing research, and with her drive to work, she found her way back into the studio.

“I was looking at all these bags that I had with papers in them [left over] from the larger pieces. And I decided I would do portraits….It was that whole thing of continuing to work. Of finding a way to work. Yes. And I started doing portraits, and I never stopped. It would get me up in the morning. It would really. And I thought the papers were so beautiful anyway. And, I think I did over 30. I did a lot of them. And I had started some even before the Covid.”

“It’s a different way of thinking [the portraits with cut papers]. It really was. And at the same time, they’re real. That’s people anyway. That’s who we are — Pieced together. Yeah.”

When no galleries or museums would show your art, Do It Yourself

“In the fifties and the sixties, you are going to know other artists because we were all trying to find places to exhibit, and everybody knows the galleries and the museums were like ‘No.’ Right. And so we had a lot of exhibitions in our own venues. We would figure out venues and sometimes they were in homes.”

“The Community Education Center (CEC) in West Philadelphia, we had a lot of exhibitions, and we met there. There were the writers, the musicians, dancers, you know, the artists. We were meeting each other, coming in contact with each other. Yeah. So, if you know one person, then you’re going to know all of her friends.

“We discussed everything – the arts that were happening at the time and what we could do. There was a need. Yeah. There was a great need. We even discussed being an artist or being a Black artist. Because we had to. And I think that was what was happening at that time.”

“Now, it’s international. I mean, the arts are international. And with all of the things that are happening with the hurricanes and all of the horrible things that are happening, [It is changing grant giving]…”grants are given to people who are really going through things a lot. Also, because it’s international. You have artists from all over the world [competing]. It’s not just the United States, not just New York. It’s places that you haven’t even heard of before.”

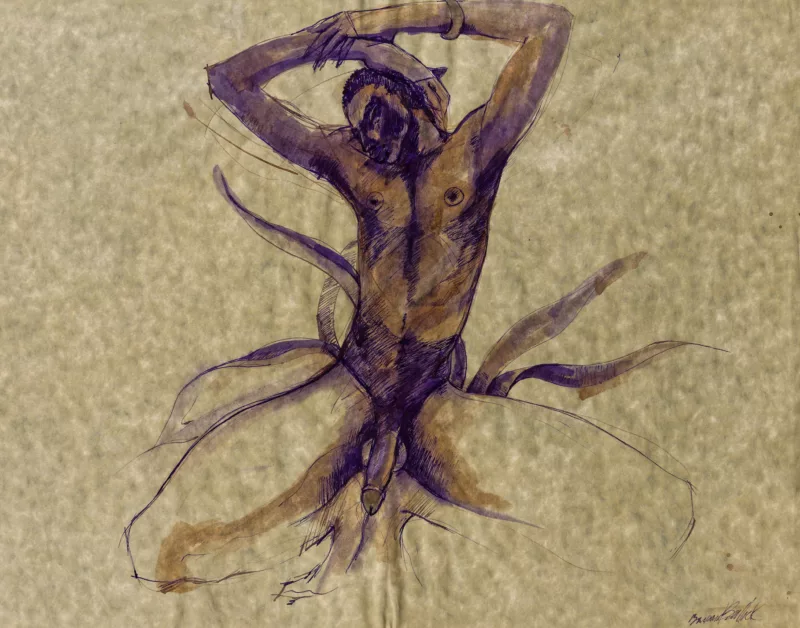

Being young and interested in love and physical love and the erotic series

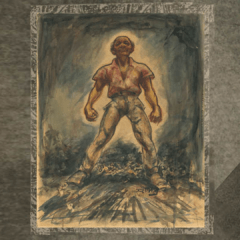

“I started out with large canvases. For some reason they were all at least seven feet, but that was an erotic series, And, I loved doing that. It was right after Model Cities closed. And, Martha Jackson and I, we were talking about what were we going to do, and I said a University asked me to be in an exhibition. I was reading a Japanese book about the warriors and it was all about love and passion and how all of the warriors had to know how to make love and on and on and on, in order to be a warrior, in order to be a strong person. So I’m thinking of what series that I would like to work on, and I know it’s gonna be about love. I’m going to do this because I think this is what the world needs. I’m going to do an erotic series. [And her friends said ‘Oh God!’]

“So if I’m going to do this, I’m doing research. I couldn’t even tell my mother, none of them, because they would’ve wanted to know what I was talking about. And I would go to all the bookstores, I would go into the areas where the guys were. And I would be right in the middle of them reading, and they were looking at me. And God, they had all these [gay sex] books out at that time, because this was definitely before HIV. So I started doing these drawings, and it was just really beautiful. And I was very serious about it.

“And I did all the drawings and all the paintings, and I was studying cultures and things like that. And I took a few of them up to the University. And, if they could have tarred and feathered me…It didn’t work out. It didn’t work out. And all my male friends ditched me. They would not talk to me. They were like, ‘You are a girl. Why are you even doing this?’ And it was just not a good thing.

“I was invited to lecture. And it was a group of males, a whole organization of gay males. And they wanted to see all of my drawings of everything that I was doing. And they would ask me questions and I was honest about it. I was like [it was] something I wanted to do. And it had a lot to do with the age that I was. With artists, when you are at a certain age, love is so prominent. All the things you feel, that’s what your work shows.

“But I’m telling you, some of my friends in Philadelphia would not speak to me. Oh, it was hard. And the guys that were at the University, they felt like I was wrong, you know? And they said that I should not have put that up at the University. I said, ‘Okay.’ Well, I kept working and I was selling a lot of this, the smaller drawings. So there was an audience.

The stigma against women artists making erotic art

“I was definitely up against it. I was extremely emotional about it. because I couldn’t understand the way people thought about it. And the anger that they showed me and that they wouldn’t speak to me. And I lost friends.

“And then a year later everybody was doing it.”

Friendship with A. M. Weaver

Barbara was good friends with A.M. Weaver, a writer and curator. They had a sisterly relationship and spoke often by phone, and went to art openings together with others. In 2017-18, Barbara was in an exhibit at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, called Gardens of the Mind: Echoes of the Feminine View. A.M. Weaver was the curator. The exhibition opened shortly before A.M. died. Barbara was especially close to A.M. and when Weaver died, she was caught short, because her friend had shielded her from the true extent of her illness.

“She died. She died during the exhibition, at the end. She would call me every day. Every day she called me. Or if she didn’t, I would call her just to say, ‘Why didn’t you call me?’ And then she would call me. And if I was up in the loft [and the phone was downstairs and Barbara didn’t answer the call], she would say [on the answer machine], ‘I know you hear me, Bullock.’ (Laughs). She would always ask me questions. She was trying to survive, you know, she had this house and everything.

“She wanted to do things. We would talk about jobs and I was like, Your voice, you have such an extraordinary voice. You could be a reader. I said, you should really do that. Sometimes when she would come here, I would have her read a page out of a book, just to hear her voice. And then when I mentioned some other jobs, [on the phone, she would say,] ‘Something’s wrong with the phone.’ And funny, I knew she was dropping the phone but I never knew that she was as sick as she was.

A few months later A.M. Weaver died.

“I said, God, how are we going to do this without her? Yeah. That was really rough. And it was like that, the big hole in your life that you’re never going to… You’re not going to meet that kind of person again.

Barbara has A.M’s voice recorded on her answer machine but, “It is too painful to listen to her voice.”

The Spiritual

“I started to write about it from something that my grandmother had said to me. My grandmother said I was her child who had died. She said she knew this. My aunt, her oldest daughter said this was true. And she said that I was that child that had passed, that I was back again. She believed that. I paid no mind to it at that time.

“I felt like I watched life, like I existed to myself, but not to others. I always felt like everything was going on, and I was watching it. You know how you stand back and you watch others, you don’t always partake or join in, in what others are doing. And sometimes you are like a spirit trying to be like others, to learn to grow until you let this feeling go. When you let this feeling go, you become the person you are supposed to be.

“But you are aware and I’ve always felt there is a strong slave spirit inside of you [a Black person]. I didn’t know it. And when I thought of that for the first time, I thought about my grandfather, who was a free man. And I only knew him on one visit when I was really small because he had passed. And he worked in the mines and he was in a cave in. And, he had brain damage and he would see so many things and I would see the same things that he saw. And my grandmother would say, ‘There both of you are, and I have a problem.’

“Because, he would see. He would take me out on the porch, and he would see these birds, and I would tell him what color they were. And my grandmother was like, ‘Oh God. There are no birds, and there definitely are no blue birds.’ I’d say ‘Yes, there are, but that’s okay.’ So, when I think about the slave spirit, I think there are times in life where I feel like not speaking, and then there are times in life where you have to speak.

For further reading, we suggest:

Woodmere Art Museum Collection

Petrucci Family Foundation Collection

Barbara Bullock: Ubiquitous Presence, List Gallery, Swarthmore College

Artblog appreciation of A.M. Weaver, who was an Artblog contributor