INTRODUCTION

Michel C. Thorpe, featured in a solo exhibition, Practice Makes Perfect at the Delaware Contemporary, was an acclaimed high school and college basketball player. A relatively young 31 years old, Thorpe holds a degree in photography from Emerson College, Boston, MA, (2016) and today lives in New York City. Although he grew up with a mother and aunt who are respected traditional quilt artists, he did not begin making his own textile works until 2018. Before that, drawing and photography were his mediums. Since he shifted to textiles, he has held several artist residencies and shown his work in group exhibitions at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angele; the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; and the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY. His textile work has been shown in solo exhibitions in galleries and museums from coast to coast.. In addition to his exhibit at the Delaware Contemporary, he will be showing his work this year at the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, MA, and the Hickory Museum of Art, Hickory, NC. In this interview with Susan Isaacs, they discuss several key works in the Delaware Contemporary show.

Susan Isaacs: Michael, what is it that you’re looking for in “Hmm what am I looking for?” and how does the title relate to the image?

Michael C. Thorpe: I’m going to take your question and kind of expand on it. It’s so funny doing interviews. I never really know where they’re going to go. But this is such a fascinating way to start. Because I think the question I’m always thinking about within my art practice is, what am I looking for? What am I doing? What? Why am I making art, you know, and it’s I think, a very tricky question, and a constantly moving target, especially growing up in the age of the post art market boom. I haven’t figured out anything, but the first thing I think about in the art process is how you can use the arts and the creative process to enrich and investigate life itself. That’s the biggest thing I’m constantly looking for, to get into this flow state. Ultimately, I came to believe that my goal was this idea of freedom.

But really, I didn’t understand what that word meant. You know, I think everybody likes to throw it around. But the funny thing I started to realize is, if you’re really free, if you’re literally allowed to do anything you want, you become stagnant, very frightening actually to be totally free.

And the thing I started to recognize in my own practice is freedom is the freedom of thought—where you don’t have to overthink anything. Don’t second guess what you’re doing, and what I started to learn is that by giving myself parameters, giving myself a structure to work with in bodies of work and within specific pieces, I found that freedom that I wanted. So, I entered the art world wanting to do everything, you know, and I still very much do, and I’m still very much actively pursuing that. But I realized that there were too many options, and then I wouldn’t do stuff to my best ability. Then, I started learning about process-based artists. I started learning about instruction-based artists. And it was very fascinating to me to learn that once I started giving myself rules, it allowed me to be even freer.

It’s really parallel to me growing up as an athlete. I didn’t know why I wanted to play basketball. It was something I was good at, and I kept doing it. In basketball, obviously, you have a set of rules. You can’t step out of bounds. You can’t do this, you can’t do that. But within that you can do whatever you want, basically within these set rules. So you’re allowed to not think and just perform and be creative. And that’s so funny and I never realized until recently about the parallels between basketball and art, of that yearning for freedom. But then, understanding that freedom. Once you put it in a structure, you’re allowed to truly breathe free, and not have to think about anything.

To bring you back to this piece [“Hmm what am I looking for?”], I was at this precipice of being over figurative, representational work. I had done a couple of big shows of that. And I’m always wary of doing iterations of the same thing, to quote unquote, develop a style. I’m always very wary of that, because to me, that feels stagnant. And I literally was sitting in my living room, and I had just seen a work by Martin Kippenberger, where he made a picture of a woman out of multiple canvases. And I was like, ‘Oh, that’s so fascinating! That’s literally a quilt. Why have I never done that?’ I made a piece of my living room, so I don’t want to do this again, but this is what’s right in front of me. I decided to create a set of 7 or 8 panels. I started looking around my living room and in each panel I drew something, and it became so much more fascinating to me than just drawing it as an entirety.

So, it’s funny, because I’ve been doing the idea of building these structures. Giving myself parameters long before I could even verbalize it. And this is a great example, because in that moment I was, ‘All right, I want to reinvent something I’ve already done. But how can I make it interesting for myself?”’And that’s a big thing. I guess if we really want to get to the heart of what I’m looking for, it’s that self-satisfaction which is so interesting in today’s world, because it’s real.

I find it hard at times to own up to what makes you satisfied in the arts, because you have so many other opinions and perspectives that are phenomenal. But at the end of the day, you have to remember, you have got to do it for yourself. You really need to find out what pleases you, what makes you interested. What keeps you going? What keeps you going into the studio? What keeps you engaged in the world? I think that’s the thing I’ve learned, and by doing so it’s allowed me to create a vast body of work at such a young age.

Susan: I think it’s fascinating that you were an athlete, but you also grew up with some makers, and your aunt owns a quilt store. Do you use recycled fabrics, or do you purchase new fabrics?

Michael: Well, most of my fabrics are new. In the beginning, a lot of them did come from my aunt’s store. But then it started becoming more impractical as she lives in New Hampshire. I’m in New York City. And her store specifically emphasizes batiks. For the most part, I was more interested in solid fabrics. What ended up happening was, there’s this phenomenal store in Massachusetts, where my immediate family is located, called Fabric Basement, which I consider my paint shop. And it’s very cheap and every color I can ask for.

Susan: You’re basically choosing your fabric as a painter chooses paint colors. For those textile people out there, what’s the machine that you use?

Michael: The machine is called a long arm quilting machine. It’s an oversized sewing machine that moves on the X and Y axis.

Susan: You show the batting. You do not bind the edges. Can you talk about that?

Michael: The exposed batting is to me nothing more than blank canvas. I really do consider the work more like paintings than quilts. But there is this funny anecdote, where I did what I considered my first art piece. I was living with my mom at the time. And obviously my mom is a world class quilter, but vastly different from me where it’s got to be by the book. And when I showed her my first quilt, I was so excited about it. I thought I had made something, and I showed it to her. And she was like, ‘That’s not done,’ and I was like, ‘What are you talking about? It’s very much done.’ And she said, ‘No, you didn’t do the edges. You didn’t put on a binding.’ What? ‘I don’t need to put a binding on.’ It became this very funny riff between us. However, the batting became more of a utilitarian thing because to add the hangers onto the piece, I used white thread, and I would stitch it through the batting, and you would not see it.

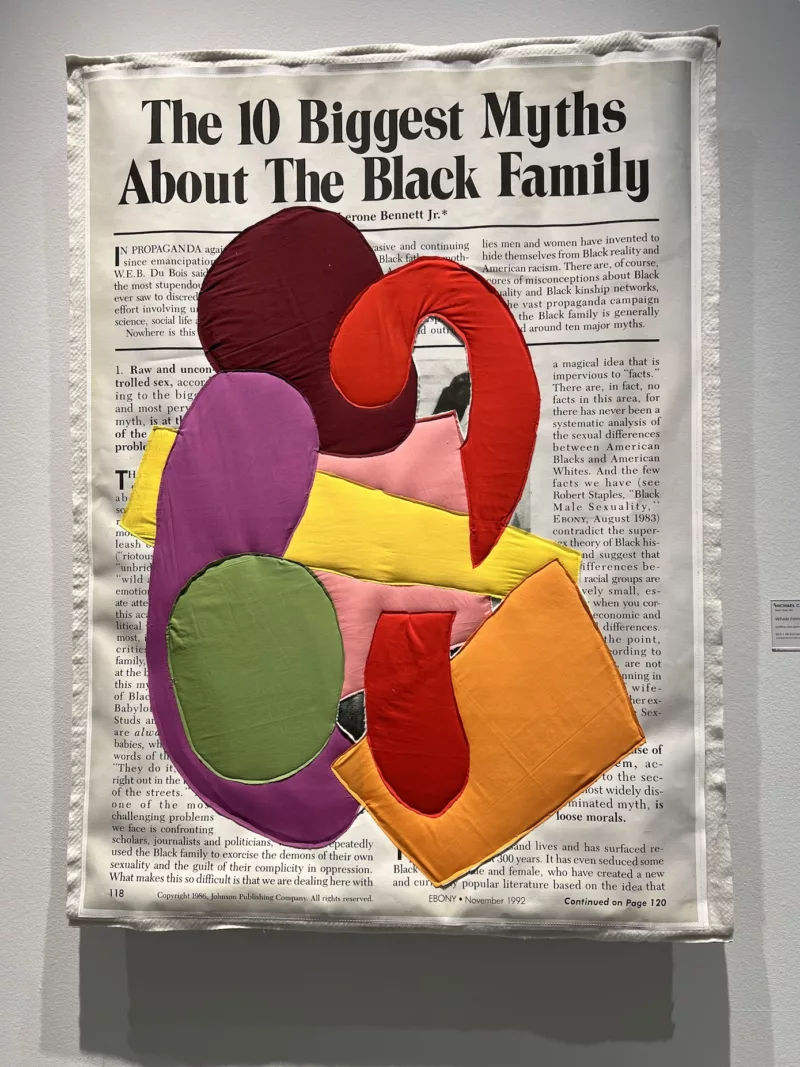

Susan: You employ a fair amount of text in your work. I also can see the photographer in you, as you compose as if looking through a view finder. The color blocking is very painterly. if you could talk a little bit about the title of “Whole Family” and then its form.

Michael: The title is directly related to the form, so we might kill two birds with one stone. Again, it goes back to this fascination of wanting to explore and having impulses and not questioning them and following them. I’ve always been interested in abstract art. For whatever reason I find it beautiful and something I’ve always engaged with. But again, not coming from an academic art background, I thought it was unattainable. And I remember one day thinking, ‘If you want to do it, just do it.’

I was in my sister’s backyard, thinking about the family that I was with right at that moment. There were six of them around me, and I don’t know why but I drew these six figures. Everything with my work starts with a drawing. I’m constantly drawing whatever it is, abstract figurative, columns whatever. At this time, I was also exploring the idea of putting quilted material on top of canvas and printed material — this intersection of photography, printing, and quilting. I also was collecting images with figures that I knew I wanted to make something on them, to replace a figure with one of my figures but more abstract. And this was one of them, and I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I kind of liked that. And I still do. That problem, what am I going to do with this? This is a page out of a magazine, how am I going to make this interesting? And it was one of these funny moments that I didn’t know at the time, but it has definitely influenced the way I work now.

And then I would start putting different things onto this image. And so basically, it was just serendipitous that this thing I drew with my family obviously correlated with the article title, and I was like, ‘Oh, that’s a perfect example.’ So, I just put it in. And then it became one of my first successful, planned abstractions.

Susan: How did you come across the Ebony article?

Michael: I came across it because I got a bunch of old Ebony and Jet magazines for source material. I was exploring this idea of appropriating other materials and printing them out. And I was actually very fascinated because I didn’t grow up with Ebony or Jet, as they were a little bit before my time. It was fascinating to see the articles they actually wrote, because my idea of Ebony was this glowing representation of Black excellence, and that it was all good. It was foolish of me, having this depiction of what Black people were supposed to be. But then I saw that they had articles that I didn’t expect. And so, I found that more fascinating and way more compelling. It added all these levels and layers to the Black identity that, silly me, I never thought would come out of Ebony.

Susan: Tangentially related to this discussion, because I’ve worked with a lot of artists of color and I always ask, how do you want to be referred to in terms of identity?

Michael: See, that’s a very funny thing that I’ve grappled with because I just think of myself as an artist, you know. I think one of the biggest things a lot of my contemporaries deal with is identity within their practice. And I’ve always found it fascinating how artists of color, any marginalized artists, women artists, you know, any artists other than white male artists have to go over these hurdles of just making art. I really try my best not to make any statements with the art. You know, I’m really more curious about the creative process and what artists do to get to the end point. I like to be identified as an artist, you know. I don’t really overthink it. But I very much appreciate you asking me. That’s phenomenal. And I love that courtesy. But yeah, no, I’m just an artist.

But I definitely had this moment of thinking about why I’m making art, because obviously I had this realization that everybody can make art, and I want everybody to make art. But to make the conscious decision to be an artist is a very deliberate act of thinking why you’re making the art, instead of just like making it. I was at that point in my career, which is so funny to always talk about points in my career, because it’s so so short that it’s like I’m talking about last year, you know. But I was at this point where I was very much just making art, being kind of lazy, honestly. I started being more critical of myself.

I always wanted to be an artist. I always wanted to show in a museum, in galleries. It wasn’t like I just wanted to make art. I very deliberately wanted to be an artist, and I thought I was shortchanging myself and people who came before me and people who were coming after me, and I realized the biggest thing I cared about is this idea of expanding what it means to be an artist, and what it means to be a human, because so often I find in our culture, in Western society we are infatuated with compressing people. And it happens in the arts where you see so many artists who become almost brands. And if they make anything else, that’s not what they are supposed to do. And I started to realize that in my own practice, I want to explore all these different themes, all these different materials, whatever, I just want to make art.

But then I realized the bigger purpose of wanting to expand what it means to be an artist and what it means to be a human. We don’t have to choose. We can do both. And there was this beautiful book I started reading on Lorraine O’Grady, where she talks about how you don’t have to choose. You don’t have to be either or. It can be both. And then I learned about Adrian Piper, who just blew my top. This is like my daily reading right now, all about her writings and stuff. And it really started to make me understand what art is about. Personal it is, and how it’s all about expanding instead of compressing. And so that’s what I started to realize where it’s like as much as I do in the terms of expanding myself and my interests and the way I work, and just seeing the world differently.

I also wanted to hopefully, potentially, open doors for other people to see that you don’t have to do one thing, you know, you could do one thing for a little bit, and then change your mind and then go back to it. One of the best pieces of advice I ever got was ‘Your career is nonlinear.’ You could double back, triple back. I’m trying to expand my consciousness of the world and my surroundings. And I think if I can have these strategies in place to attack it, then revisit it. I want to be a professional Newbie, you know, and every time I make work, I want to try to come at it like it’s brand new. Just try to come at it with all my sensibilities and be open to whatever is going to happen.

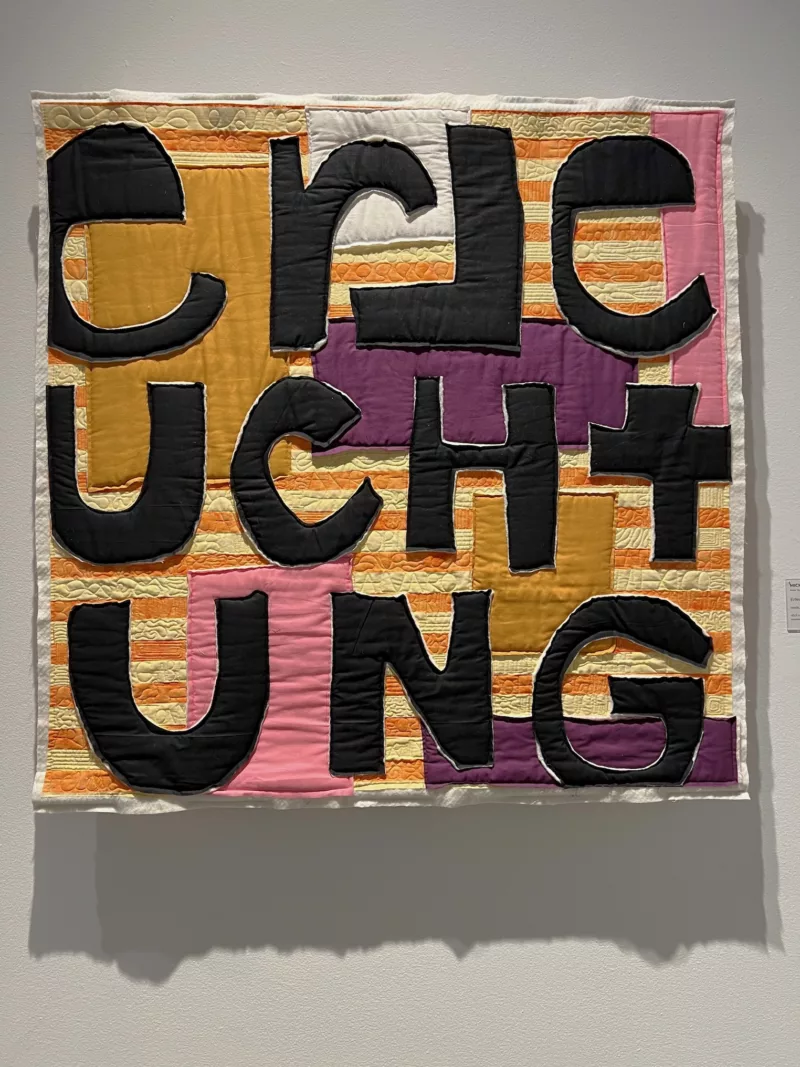

Susan: My German is quite rusty, but I thought, I know that word, Erleuchtung. I looked it up to be sure, and I love it: epiphany, inspiration, illumination. And I think that relates to what you’re talking about in being an artist.

Michael: I got exposed to text in art specifically from works by people like Richard Prince and Christopher Wool. It was so fascinating. I did not grow up going to museums. Even though I feel like I’m versed in art, I didn’t grow up exposed to art in that classical sense. But then, when I started to see stuff that I liked, I would gravitate towards it, so when I started seeing text, it was this visceral response of ‘That’s cool.’ You could do anything on a canvas, and you just decided to put some words on it. I thought that was very cool and modern, so that made me very engaged with it.

Most of my inspiration for art is from art. I never really think of myself as an artist who makes art about art. But I’m definitely an artist who will see something and instantly gravitate towards it, and then I want to do that and not overthink it.

I stumbled upon the word [Erleuchtung] while studying Martin Kippenberger. The funny thing is, I misquoted this word so many times that I decided to make something. I’ll be inspired. I’ll do it and then it’s done, you know. Then I’m moving on. I don’t hold on to things. I’m not attached to the objects as themselves, but for this one I was so much more fascinated in the actual forms. The letters made more than the word. And this is why I love talking to people like yourself, and curators and people invested in the arts because they are interested and they do deep dives that either a), remind me of something that began the work, or b), illuminate something about the work to me that I didn’t think about, because that’s the essence of art for me.

At the end of day, I hope the works start conversations. I don’t know what I’m doing. I’m just going to be upfront that I don’t know what I’m doing. I hope I start conversations. I’m not trying to ask questions because I’m never going to ask the right questions. And I, for sure, don’t know the answers. So, this is a beautiful piece of trying to make something interesting, something sensory, something great to look at. And then, if you feel so obliged to figure out what it means, great. It’s crazy looking at this show through your eyes. A lot of these works are firsts that were successful firsts. I felt this was my first successful word piece, you know, playing with the letters as forms, instead of not trying to make a statement, not trying to be like ‘These are words, and you have to deal with these words.’ And so that’s what’s so cool to see this piece and on top of that it’s always fun to speak one language and then use another language. In art. I always find that very fascinating.

Susan: I think it is a very successful piece, and the underlying abstraction provides a painterly vocabulary, but I really love the word, too—the meaning of it. It might be by accident, or it might not be the first thing that you intended, but that doesn’t mean someone else might not read it differently. I also think there’s a joyousness about your work. It’s not just a joy in terms of color and form, but it’s a joy in terms of outreach to humanity, to people.

Michael: Thank you. That means a lot to me. I think in a lot of ways art has become this insular and privileged thing, and all my North Stars in the arts always talk about no separation between art and life, and that’s what I think about so often. You get lost, especially when you’re doing it at the level I am. You kind of forget that art is this thing that is a tool to navigate the world. And I think that’s the biggest thing I always try to remember on those dog days. And it’s so funny when I say dog days about making art. But you deal with so many of the same problems that everybody deals with, you know. And it’s so amazing to hear that because at the end of the day I’m constantly reminded I’m just exploring my own emotional, mental, physical landscape and expressing it and then hopefully reaching out to people, and hopefully they get something. And so that’s why it’s so amazing to talk to you about it and hear your opinions, and that reminds me what it’s all about.

Michael C. Thorpe, Practice Makes Perfect, Delaware Contemporary, Wilmington, DE, to May, 26, 2024.

For additional reading, we suggest

Many Artblog articles on quilts, quilters and fabric arts