In the year 2024, artificial intelligence is a looming specter. The benefits of AI are easy to imagine, but it would require magical thinking to believe that AI won’t significantly harm the fields of journalism, writing, politics and art. Are we strong enough to resist this force? Are we wise enough to embrace its presence?

What our individual role will be in the time of artificial intelligence is a heavy question to tackle, yet that is exactly what Data Nation: Democracy in the Age of A.I. seeks to do. The exhibition is on view at the National Liberty Museum, a location that may be unfamiliar for some and surprising for those who were familiar with the museum in the early aughts. Located on 4th and Chestnut, between the Museum of the American Revolution and the Ben Franklin Museum, National Liberty Museum has been a hub for tourists and learners who are exploring the concept of liberty in modern society. The intricacies of how the NLM was conceived, debuted at the turn of 21st century and flourished in a post-9/11 America could be an entire essay in itself. It will suffice to conclude that in recent years, the museum has reapproached their modus operandi. Recent programs and exhibitions present an updated point of view and give more support towards artists and the local Philadelphia art community.

That brings us to Data Nation, an exhibition that encourages viewers to consider how AI could affect their own liberty and how current technologies both progress and compromise our society. Data Nation is an educational tour through the capabilities of AI and the concerns being raised around its rapid growth. The exhibition is populated with artworks from local creators: Roopa Vasudevan, Emmanuela Soria Ruiz, Jim Strong, and Lane Timothy Speidel. Immersive pieces are also present, one created by Landau Design+Technology in collaboration with the NLM and the other created by Center for Immersive Media at University of the Arts, also in collaboration with the NLM.

The didactics are the central focus of Data Nation; the artworks function as supplemental materials. This is an inverse of the typical contemporary art gallery or museum format, in which wall text offers auxiliary information for the physical works. For a show centered on science, this reversal is effective; viewers are taking in facts and process them through aesthetic experiences.

The standout piece of the exhibition is “The Echo Chamber.” Created by the NLM in partnership with the Center for Immersive Media at University of the Arts, the interactive installation mimics the effects of a digital echo chamber, a manipulation perpetrated by social media platforms in which an individual is constantly presented with opinions similar to their own. In “The Echo Chamber,” animations are projected across the top of a canopy tent. When visitors enter, they encounter a tablet that prompts them to type in a self-held belief. Once they do, the system uses ChatGPT to generate a litany of phrases that replicate the one typed in. These phrases pop up across the top of the tent and are read aloud by artificial voices. For example, typing in “I believe that restrictions need to be placed on AI usage” might initially prompt the text “Restrictions on AI usage are needed.” The number of text bubbles and voices build to an overwhelming crescendo as the generated phrases become more complex. The experience is stunning, and hopefully “The Echo Chamber” can be experienced by the public after the exhibition’s run.

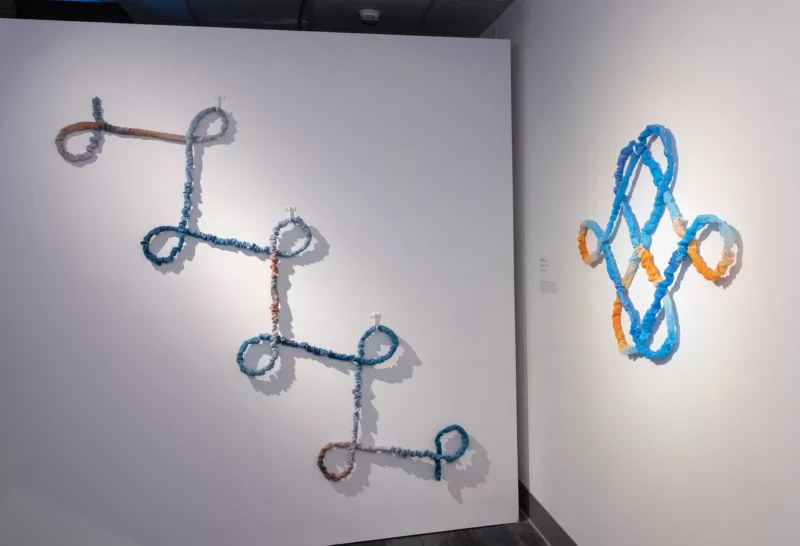

It’s a risk to present traditional artworks next to such a innovative piece because objects feel flat when placed next to screens. Emmanuela Soria Ruiz’s tender textile pieces are described as an intentional antithesis to the digital world. A slow interactivity occurs when viewers gently tug on the fabric to reveal the lettering stitched onto the bunched material. Similarly, Lane Timothy Speidel’s textile works also invite patient interactivity. Behind Speidel’s hanging quilt and wild net of various strings, a tin is affixed to the wall. Lean in close and a soundscape created by the artist can be heard. Jim Strong also presents a hanging sculptural piece incorporating sound; however, it is difficult understand how to activate the mechanics of the piece without clear instruction, which I somehow missed during my two visits.

Roopa Vasudevan presents a body of work that is a bridge between the scholarly and creative. “dataDouble” is presented as a grid of framed portraits. The people depicted are participants who downloaded a browser extension, designed by Vasudevan, that can track internet usage behavior. From this data, the artist created a rubric by which the original photos would be edited. For instance, the level of saturation in the edited image corresponds with the diversity of news sites that the subject would visit. The amount of contrast applied corresponds to search engine usage.

The resulting portraits are a visual metaphor, emphasizing how data companies can have an imperfect, but still fairly accurate, understanding of who someone is based on their online behavior. Vasudevan’s work also exemplifies how algorithms use comparison points for pattern recognition; if a viewer can visually see how some photos are grainier than others, imagine what an advanced computer is able to detect by comparing the world’s data points.

Data Nation represents a fascinating change at the NLM. By focusing more on local and contemporary art, the museum stands to become a new platform for artists, especially at a time when exhibiting opportunities are dwindling. However, the NLM does require a ticket to enter during regular hours and it’s not likely that art viewing audiences will pay for entry and will only attend during special events and receptions. The primary audience will never be the same as the audience for the ICA or Paradigm Gallery, but the NLM stands to cement itself as a platform for artists who wish to have their work showcased to a more mainstream audience. That would be extraordinary to witness.

Data Nation, on view at the National Liberty Museum until March 18.

Read more Artblog coverage by Logan Cryer