Elizabeth Johnson has been writing off and on for Artblog for a dozen years, recently focusing on interviews with Philadelphia gallerists. This year, having doubled down on her painting, she’s stepped back a bit from writing. The output of that renewed drive to ‘get it down on canvas’ can be seen in her one-person show, The Cost of Sleep, gracing the second-floor front gallery of Gross McCleaf Gallery. This seemed like an ideal time to turn the tables, and for Artblog to ask about her creative journey and to give Elizabeth a chance to speak about her work. The conversation has been distilled and edited for continuity and readability.

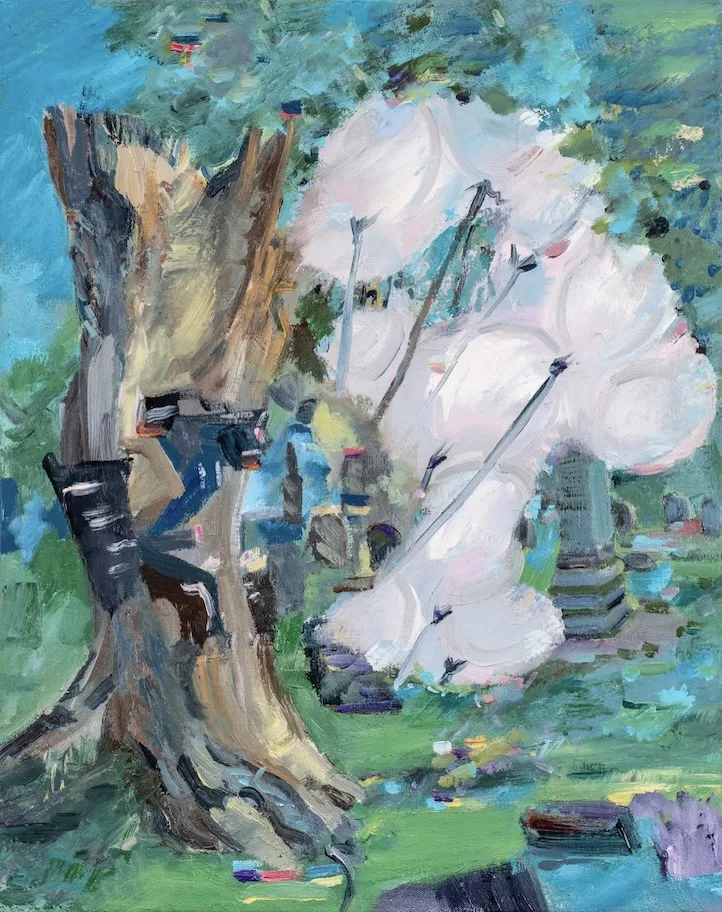

In her paintings, images glide and sway through painterly space. The constant motion mirrors the half-aware way that thoughts and images appear and disappear in our mental landscape. The images all manifest together but defy narrative…purposely refusing to connect in any explicit storyline. According to Elizabeth “I don’t want to have the painting speak to me as a story. If I put objects together that look like they’re going to suggest a narrative, I’ll get rid of one thing and search for a fringe subject…I destroy a lot of what I paint.”

What drives this ‘anti-narrative’ approach? That’s an interesting story in its own right. Elizabeth comments “I come from a family of Irish storytellers, and everybody is always competing to tell their version of reality. I’ve always been quieter, a really good listener. Though I love my family, it’s been aggravating to have all those voices in my head. Everyone is so verbal and opinionated about everything. It’s tiring to be on the receiving end of that for decades. Peace of mind for me is observation and exploring the mysterious, manifesting side of life.”

Building and Erasing

The work we see [at Gross McCleaf] is the result of a long, patient process of building, erasing and exploring, resulting in passages that have a subtle and often delicate, layered quality.

Elizabeth comments “As I’m working I might smear out entire areas; I’m constantly taking a palette knife or a rag, to blur or destroy what’s accumulated to make room for something new. That moment of sacrifice and engaging chance and potential is really a big part of my painting. I love the split second where an image is both developing and dissolving, risking success and failure. How can I repurpose the thing that I’ve destroyed or that didn’t work? I’ll look at my source photographs, choose another image and begin again, building on the canvas’s color or texture.”

For Elizabeth the layered nature of her work has roots in some very earthy early life experiences. She states “I grew up on a farm, we were always cleaning stables. Horses are kept in stalls on clay floors. When you’re mucking stalls, you’re also digging up part of the clay. I’m at home on a filthy, plowed-up surface; painting and farm work share the thrill of sinking tools into rich, tactile material.”

Life Influences

As Elizabeth and I talked about her development as an artist and the influences that have led to this body of work, the other life experiences that forge her current aesthetic began to emerge. Beyond working the earth and growing up in that household of strong-willed narrators, she continued, “Landscape painting was always a big part of my upbringing. Many of my family members are artists. Four cousins, my mom and two aunts all paint. I was lucky to be introduced to drawing and watercolor painting early in life. Picture a group of women sitting around a porch table, painting a lake, eating cookies and drinking tea. They’re all talking at the same time and shushing each other–it was a special kind of chaos that the males of the family fled.”

Elizabeth continued “…When my husband and I lived in San Francisco I didn’t get an MFA but studied the figure for many years at the Mission Cultural Center where I met many friends. I would set up an easel on Ocean Beach in the Sunset District and draw or paint the ocean. That’s when moving water became important. I studied the way waves come toward the shore and break over and over again.”

How she earned a living had yet another influence, forming the way she embraces the surface of a painting. Elizabeth explained “We made our money by hanging wallpaper, which was a high-end business. I developed a keen awareness of how a flat pattern enhances surface architecture. For a time, I made oil paintings that combined figure drawings in wallpaper-like patterns. The paintings in this show are built of five or seven distinct zones that recall a repeated pattern, though each view is different. I’m interested in multiplicity and randomness.”

Our discussion moved on to the topic of dreaming. It appears Elizabeth is almost exclusively a lucid dreamer. The relationship between her dream state and painting is hard to miss. “I’m usually very aware that I’m in the dream. I’m always exploring, I’m always going over hills or going through doorways or looking. I don’t know what I’m looking for, but I’m definitely not yearning for something in particular. I’m moving forward and thinking about what comes next, and that’s really pleasurable for me.”

The “Anti-Influence” of David Salle

Elizabeth also talks about the influence, or perhaps we should say anti-influence of David Salle on her work. This led us to an interesting sideline about how her husband had engaged in a dialogue with the well-known artist. “It’s funny. Matthew, my husband, wrote David Salle, responding to one of his reviews in The New York Review of Books. Salle is an excellent art writer. They wrote back and forth a few times. I still find David Salle’s work difficult to enjoy, but I got so much from looking at his work. I use his idea of random-seeming juxtaposition in my painting.”

What differentiates Elizabeth so strongly from Salle, though, is that in her painting objects don’t work in tension like they do with Salle: instead, they simply co-exist, side by side. And where Salle points us outward to the culture at large, Elizabeth points us to our own internal psyche.

True Freedom

The pursuit of freedom seems to underlie and animate so much of Elizabeth’s art. This understanding crystalized during our conversation when Elizabeth talked about how she prefers landscape to figuration. “My paintings are mental constructions expressing escape from people and their voices. I prefer landscape to portraiture or interiors. I have a deep need to see open vistas, sky, and fields. Every painting in this show includes open areas of abstraction that offer respite from movement and change. Juxtaposing abstraction with recognizable objects signals that you are looking at an imaginary, internal space. To me the paintings feel busy but quiet, but viewers might feel differently.”

As we closed our discussion, Elizabeth recounted how a friend had recently raised an interesting contradiction. “(A friend) asked me, why don’t you only use abstraction? I considered that for a second and I thought, well, I can see why she would say that because she sees that I enjoy abstraction. I didn’t know how to explain the need to include both real and abstract elements to her except by saying that making, breaking and remaking what binds you is extremely cathartic.”

When we look at these paintings and start to trace the influences that have brought Elizabeth to this body of work it all begins to add up: ‘anti-narrative’ use of representation; influence of water and earth; lucid dreaming; and layered surfaces built through cycles of creation and destruction. To see, first hand, how ‘the objects that bind us’ have been set free come see The Cost of Sleep at Gross McCleaf Gallery through March 30. Visit Elizabeth’s website at www.elizabethjohnsonart.com.

For further reading

Pete Sparber’s interview with Sam Connors of Da Vinci Art Alliance

Elizabeth Johnson’s interview with Sara McCorriston of Paradigm Gallery and Studio