And, ‘How A Shape Becomes A Memory,’ 2021, Acrylics, Flasche,Molotow markers, colored pencil, water soluble crayon and paper on wood panel 48” x 48” x 2”. Photo credit: Jaime Alvarez

The three artists in the current exhibition at the Fleisher Art Memorial seem at first to be so completely different from one another that I almost despaired of talking about them in one space, before coming to my senses. We have the dream-like surrealism of Joseph Lazaro Rodriguez, the expressionistic graphic designs of Erik Ruin, and the techno-environmental conceptualism of Sean Starowitz. Yet despite the obvious differences, two things, broadly speaking, unite them. For one, they share an underlying stylistic sensibility rooted in 20th/21st century alternative comic book traditions. And for another, they share, I believe, an implicit conviction that the art of our time must in one way or another identify and grapple with our existential dilemmas. In that sense, they really do answer the goal of this year’s jurors, James Britt and Kathleen Eastwood-Riaño, to find artists who “convey compelling narratives about the precarious nature of our existence through our bodies and physical environment.”

Joseph Lazaro Rodriguez may be the most immediately captivating of the three. His Fleisher project, The Currency of Promises, draws on the religious tradition of fabricated votive offerings— objects and paintings that are displayed in tribute to God’s healing powers, and are thus a kind of currency in the spiritual exchange between the Divine Spirit and humans. Rodriguez references his own religious background—in Catholicism and in Santeria—as a Cuban-American, and the works in the show feature paintings and cloth soft sculptures that represent the body part that has been successfully mended.

Rodriguez’s intensely saturated colors draw the viewer’s eye into largely biomorphic forms that seem born from a fusion of Surrealism and Latin American magical realism; but his imagery also has roots closer to home, based on the artist’s prior work as a hospital nurse, specializing in cardiac surgery. Here is a heart in a body cavity; there an indescribable organ hanging loose; there an occasional medical instrument; and everywhere there are legs and feet, the most common currency in the votive tradition.

Rodriguez’s Fleisher show is consistent with the broader range of practice visible on the artist’s website—multimedia pieces, sculptures, and video projections—demonstrating Rodriguez’s characteristic fusion of spiritual themes with a sophisticated incorporation of the idioms of modern art (he’s a PAFA graduate). While drawing on spiritual iconographies, The Currency of Promises stands outside of vernacular practices as a contemporary aesthetic commentary on an ancient religious tradition.

Erik Ruin comes to the Fleisher show with an archive of multimedia work over a period of twenty years, including a history of collaborations in video projection, theater, installation, and art-book production. He is the most overtly political of the Wind Challenge artists, with an affinity for radical utopian traditions, and his Wind Challenge project, Letters from German Exile, is based on three powerful literary texts that are rendered graphically as separate silkscreened books. Their aim, as Ruin puts it, is “to reflect on relevant contemporary themes such as incarceration, the state, the rise of fascism, trauma, survival,” etc.

The whole point, of course, is to consider these abstract themes in terms of how they are embodied aesthetically, and one way to formulate the special challenge in Ruin’s project is to ask, with these three art books, How can you illustrate a powerful text without overpowering it? Is there a necessary balance between word and image?

That balance is perhaps most successful in “Until We Can See Each Other As Free Human Beings,” based on letters written by Rosa Luxemburg while the Marxist revolutionary was imprisoned in Poland for her anti-war activities (1916-18). Here, the letters are represented as drawn script in long enough passages that we can follow the poetic flow of thought. Ruin’s drawings are boldly abstract, yet complementary.

A different relationship between word and image is apparent in Ruin’s version of Bertolt Brecht’s 1939 poem, “To Those Born After.” Brecht’s poem, written in exile from Germany, is the most eloquent of the three texts, conveying the stunned sadness of that apocalyptic moment and its social turmoil. (The poem begins, “To the cities I came in a time of disorder/ That was ruled by hunger.”) Yet as strong as the text is, Ruin’s vibrant silk-screen drawings create a new work separate from the poem, outshining the words by virtue of their color and masterful compositions on each page. It’s the most impressive of his three art books.

Less successful, I think, is Ruin’s version of Ulrike Meinhof’s “Letter from a Prisoner in the Isolation Wing, June 16, 1972 to February 9, 1973.” Meinhof, a leader of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, was a revolutionary terrorist in prison on charges of murder, and her letter portrays the sufferings she endured while in prison, beginning with the line, “The feeling your head is exploding (the feeling the top of your skull should really tear apart, burst wide open).” In the sample on display, the words are projected onto the page in half a dozen utterances that seem to emanate from a distraught seated figure (accompanied by two doppelgängers), drawn with overwrought lined veins on her arms and legs. Your eye swings between the words and the images, each competing for attention like two kids waving their hands in a classroom.

What’s also problematic is construing Meinhof as a martyr to the State, if that’s the implication. While her letter may have been read by some as an echo of the sufferings of Jews during the Holocaust, we recall that in 1972 the Red Army Faction published Meinhof’s pamphlet, “Lead the Anti-Imperialist Struggle” (Den Antiimperialistischen Kampf Führen!), written during her imprisonment. The essay extravagantly applauds the Palestinian “Operation Wrath of God” terrorist kidnapping during the 1972 Munich Olympics that led to the deaths of eleven Jewish athletes, as Jeffrey Herf has detailed (Undeclared Wars with Israel, Cambridge UP, 2015, 190-93). Ruin’s art book can’t do justice to these complexities.

The third artist in the Wind Challenge is Sean Starowitz, whose work centers on a world mediated not by spiritual powers or messianic politics but by the shimmering screens that dominate our daily consciousness as we struggle with the pernicious relics of our fossil histories. Starowitz has been a practicing public artist for nearly fifteen years, working in Kansas City, Louisville, and Bloomington, where his work revolved around how communities think about their histories, their monuments, and their public spaces. More recently he completed his MFA at Tyler School of Art and Architecture, and his work has focused on the environment and climate change. (See the short video, No One Can Embargo the Sun—on his website— a powerfully ironic montage of film clips, inspired by Jimmy Carter.)

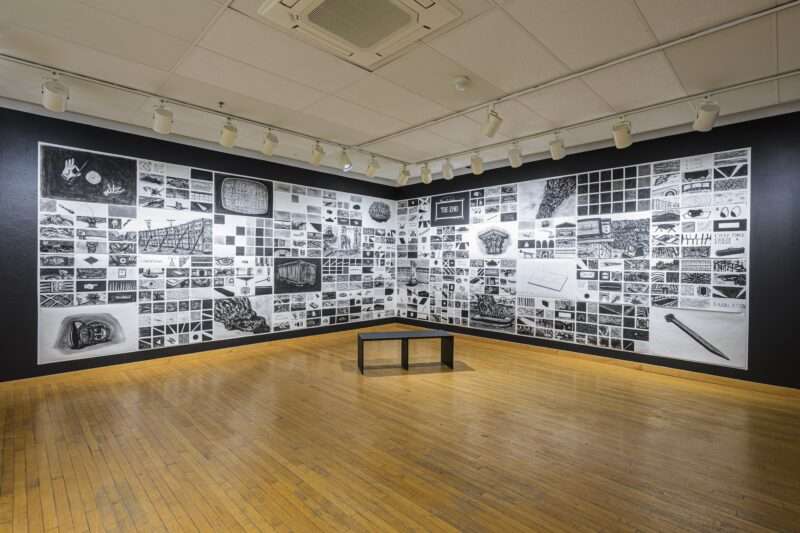

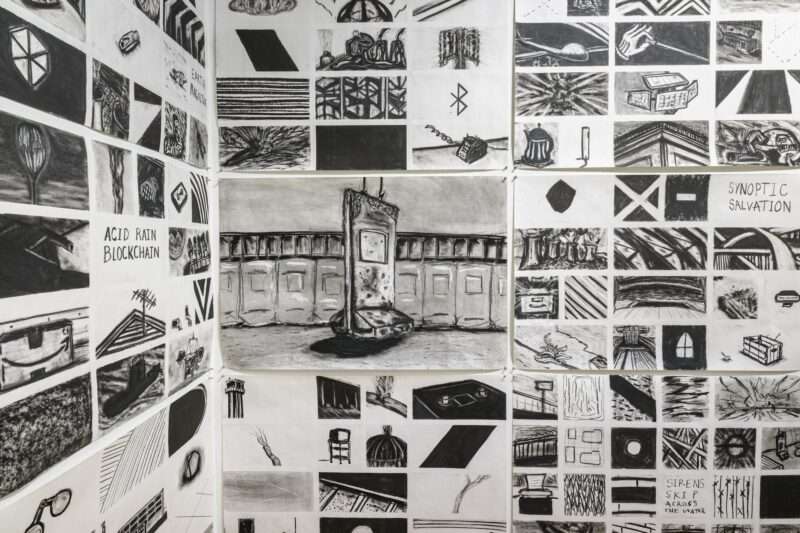

The Fleisher project, Acid Rain Blockchain, is an encyclopedic gathering of images relating to the environment, aiming to raise our consciousness about the way media have structured our understanding of technology’s power over the ecosphere. Acid Rain Blockchain — the title sounds like a punk band—has three elements: a television set with a loop of climate news; an air filtration system using charcoal filters; and, on the L-shaped walls facing the TV, a giant mural comprising a grid of images drawn in charcoal. (Given the renewability of charcoal, the medium here is part of the message.)

In using the grid to organize the mural, Starowitz creates a pattern of sixteen single-image panels mixed into the multi-image panels that occupy most of the mural’s real estate. The large panels feature a seemingly random assortment of things —e.g., a TV screen, a Bremmer Wall, a Corinthian column. Meanwhile the miniature grids seem equally disconnected, though within each grid of 24 mini-images, the drawings are thematically and formally unified— e.g. images of abstract data, architectural details, graphic icons. Every now and then, a phrase will stand out from the grid, teasing us with promised meaning: “BLOT OUT THE SUN”; “SYNTHETIC LANDSCAPES”; “SYNOPTIC SALVATION,” etc. There are hundreds of separate drawings, and the variety of imagery — everyday objects, technological artifacts, signs, symbols, and abstractions — is staggering.

But what does it all mean?

Starowitz invokes cinema and the novel as analogues, but the mural is more open-ended than either, seeming to eschew narrative. Instead, it poses a riddle: How can we liberate ourselves from the techno-universe? I won’t pretend to offer a definitive answer, either to the mural’s meaning or to the riddle, but here are a few things I am picking up: I see in the upper left a large panel drawing in comic book style of a magician’s hands (with echoes throughout the mural), an ironic comment perhaps on our fatal belief in the magic of technology. I see at the bottom of the same column a drawing of a bust of the anachronistic Karl Marx, on its side, seemingly pulled from his pedestal, as if Starowitz is saying that we need to get beyond the relatively simple world of Marx in order to understand the intersecting forces of capitalism, technology, and media that control our lives and the environment in ways that may already be irreversible. And the last large panel is a single long nail — a call to return to basics and rebuild our ruined world? Or is it the final nail in our collective coffin?

The project’s title might express that pessimism, in that a “blockchain” (if I can trust AI) is a term from cryptography that describes a database that is “immutable” once information is entered. I assume that’s what makes it useful in Crypto Land. By calling his work Acid Rain Blockchain Starowitz may be saying that the climate data is itself ominously locked in. If liberating ourselves from the chains of climate change is our goal, then we need to begin with an understanding of the coils and loops (media, technology, fossil fuel) that bind us.

I can’t quite get Topsy out of my head, but it’s surely better to end this review with what Gramsci said, repeating Romain Rolland: “Pessimism of the intellect; optimism of the will.” In our topsy-turvy world, a time of moral, political, and technological upheaval, the Fleisher’s Wind Challenge offers three wildly different assessments of the human condition and three powerful models of what it means to be an artist today.

Wind Challenge Exhibition 2 at the Fleisher Art Memorial, 719 Catharine St., featuring the work of Joseph Lazaro Rodriguez, Erik Ruin, and Sean M. Starowitz, to May 10, 2024.

Read more reviews on Artblog by Miles Orvell.