Guest Post by Chris Funkhouser

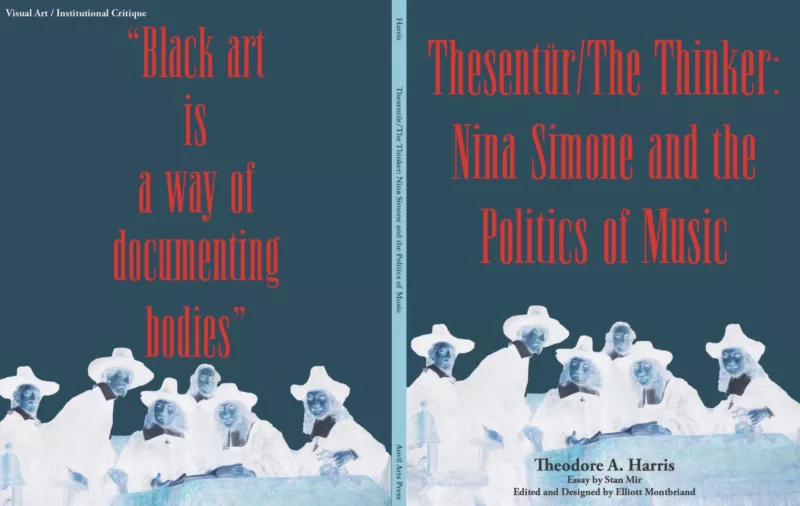

Thesentür/The Thinker: Nina Simone and the Politics of Music is the catalog for a forthcoming exhibition by Theodore A. Harris, scheduled to be displayed at Center for Emerging Artists Gallery, Philadelphia, PA, in November and December, 2024 (opening November 7, 2024). This forty-page book, however, does more than catalog an art show by Harris, whose dynamic, politically-charged collages are highly regarded by everyone who knows them (previous collaborators include Amiri Baraka). In addition to collecting a sampling of Harris’s topical triptychs, including those made after the original exhibition was conceived and approved for display in 2019, the book documents and tells the exhibit’s backstory by way of multiple voices, divulging both the germination of the project, and reasons for cancellation at its initially slated venue. This publication thoroughly succeeds in handsomely documenting a nine-piece mixed-media, site-specific installation designed to be shown in the lobby of the Curtis Institute of Music (Philadelphia), yet accomplishes much more than that.

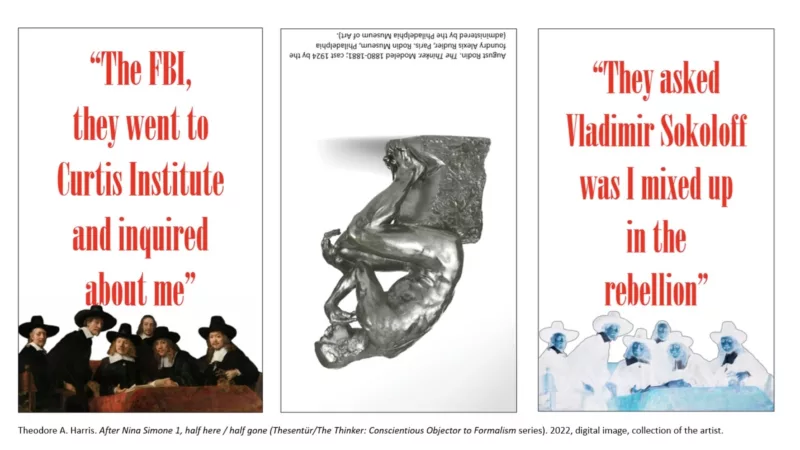

From different voices a narrative is told. Stan Mir offers a contextual essay, “Mixed up in the rebellion”, explaining how and why Harris’s appropriation of a Rembrandt painting becomes the “rhythm section” of the show. Mir observes how Harris’s work stems from a type of disenfranchisement observable throughout history, and how Harris’s aggressive art (at least in as much as it asks us to think), raises multiple questions that are meant to instruct. Harris’s initial exhibition proposal, which charts the exhibit’s domain and purposes (“to activate questions of the inequality marginalized groups deal with in our nation’s orchestras”), as well as a Manifesto regarding Thesentür/The Thinker, are included. The letter Harris received from the Artistic Director of Curtis Institute of Music, explaining why they could no longer host the exhibit, also appears. Through these narratives, a clear picture of Harris’s experience during each phase of the project emerges.

Nina Simone, herself amongst the most righteous artistic figures of the past century, fits into this because of the bias she experienced at Curtis in her youth (and after, throughout her career). Her words are the inspiration for two pieces that appear in the catalog (other touchstones in the book include David Hunter, Fred Moten, Robin D.G. Kelly, Rizvana Bradley, Romare Bearden, Katy Siegel, and Baraka). The connection to Simone, whose struggles in the music business/industry due to her polemical, anti-racist orientation, is anything but haphazard (as late as 1997, a bomb threat threatened to cancel a concert of hers I attended in Newark, NJ). Because Simone was forthright, authorities and xenophobes were afraid of her, doing everything possible to impede her success. Fortunately, like those who may have attempted to thwart Harris’s messaging, they failed.

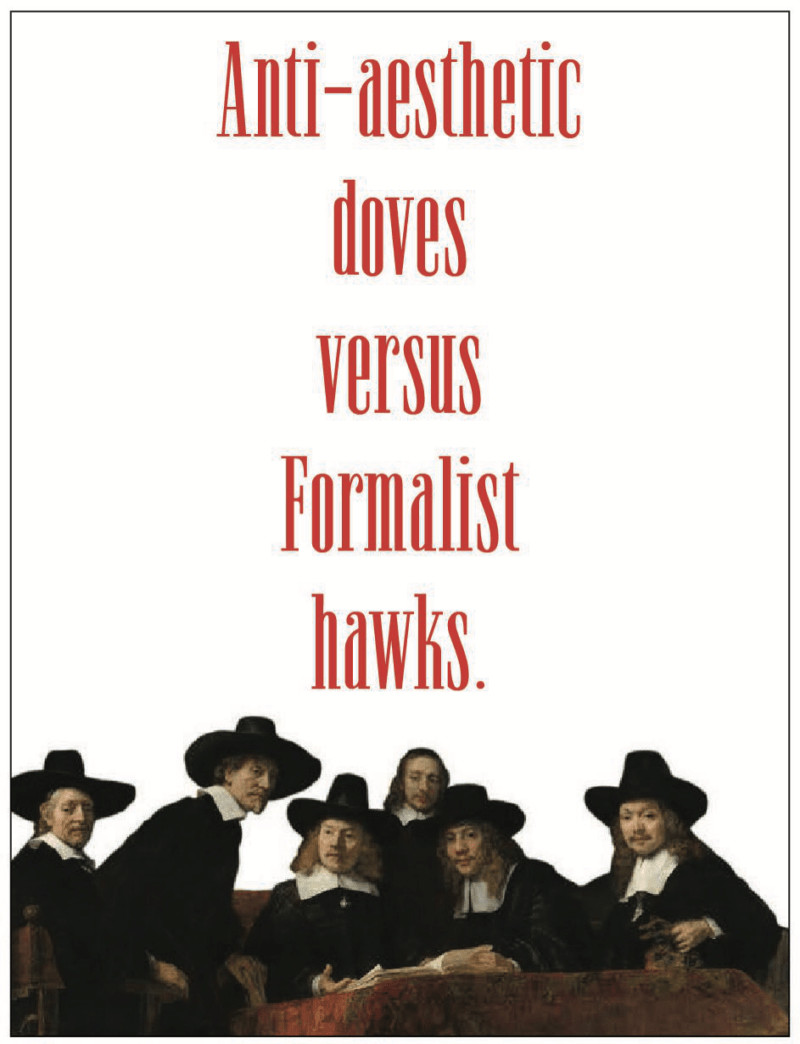

As mentioned above, Harris’s investigation in Thesentür/The Thinker broods on a Rembrandt painting (“Sampling Officials of the Amsterdam Drapers Guild”). Harris then co-opts and graphically resituates the symbolism of Dutch Masters cigar boxes (whose signature image is based on the painting), playing with the iconography and directly appropriating the typeface used on their packaging. This gesture, coupled with the subtitle accompanying all of the works included in Thesentür/The Thinker, “Conscientious Objector to Formalism Series”, firmly establish Harris’s anti-colonial, anti-formalist position. These foundations are extended by Harris’s use of an inverted photo of Rodin’s “The Thinker” at the center of two of his triptychs. This motif, reminiscent of Harris’s earlier compositions built around images of an overturned U.S. Capitol building, signals distress (as with a flag flying upside-down), along with several other possible meanings, such as dominant upside-down thinking perceived by the artist. We are seemingly living in a civilization where thinking deeply, along with thinking in terms of seeing everyone as being equal is not always, or even very often, guaranteed, as indicated by Harris’s recurring inversion of Rodin’s famous icon.

Harris’s work embraces bold “anti-aesthetic” qualities, and is not produced to make all of its viewers feel good. He rightly calls out Handel for, “buying and selling shares in the Royal Africa Company” (p.6) and proclaims more than once, “Clement Greenberg’s forked tongue eats people” (pp. 11, 16)–in the latter case buffering critique with comedy as well as can be. Harris’s “Surgeon General’s Warning” (p. 7) suggests what’s inferred in Harris’s works are not good for the public’s health, even as he knows messages conveyed in his work need to be projected.

Thesentür/The Thinker also contains an extensive “Selected Exhibition History” of Harris’s work. The comprehensive litany it contains reflects the trajectory of, and serves as a broad introduction to, Harris’s work, illustrating a strong supporting structure that exists behind his efforts. This book efficiently and thoroughly portrays a gifted contemporary artist’s labors. If there is anything that could be criticized, it would be that the publication in places seems hastily arranged. I noted some imperfections in the editing and formatting of information, although these attributes may be part of an intended aesthetic. In the end, even if the tome’s production is not flawless, it matters little, as Thesentür/The Thinker’s intentions are clearly communicated, and who cares if a book is not perfect?

Thesentür/The Thinker represents expansive documentation of a relatively small art world incident which has significant implications. The Dutch Masters, in part, make Harris who he is, and offer him something to respond to. Cannibalizing the commercial product’s typeface, playing off its connection with the famous painting, is an important part of the message transmitted. Though not stylistically, the Dutch Masters are inextricably part of the artist and what he says in his reformations of context and possibility throughout this work. Harris’s project here, a type of critical scrapbook of the history of his Thesentür/The Thinker series, emerges as being no less than a scathing critique of art history. Verbally rendered, over and again, are the inequalities African-American artists in all genres have faced; this book is a deep case study on the subject. In Thesentür/The Thinker: Nina Simone and the Politics of Music, Harris invokes Rembrandt, Rodin, Simone, and many others who have mastered the expressive forms they used. In my view, when you draw from and/or reconsider the “masters”–of thought, of form–within your own creative vision, you are more likely to achieve something like mastery yourself. In this instance, at this historical juncture, Harris has certainly done so, and this book portrays a brilliant episode, one instance in the life of a Black Artist. Through it, we see how the artist conceives of, and navigates through, processes and struggles in his own ideas and experience.

—Chris Funkhouser, Staatsburg, NY, 2024

Christopher Funkhouser is a writer, musician, and multimedia artist. Funkhouser teaches at New Jersey Institute of Technology, is a Contributing Editor at PennSound, and hosts the Poet Ray’d Yo program on WGXC in Hudson, NY. Website

Nov. 7-Dec. 20, 2024: Theodore A. Harris, Thesentür/The Thinker: Nina Simone and the Politics of Music, Center for Emerging Visual Artists (CFEVA). Opening Reception: Thursday, Nov. 7; exhibition catalogue available. Website

For more Artblog coverage of Theodore Harris, listen to a 2016 podcast with Jennifer Zarro talking with the artist, The Woodmere 76th Annual is a juried exhibition and Public History Truck.

Further reading:

https://field-journal.com/issue-22/interview-with-theodore-a-harris

https://theodoreharris.weebly.com/

https://asapjournal.com/feature/theodore-a-harris-master-unmasker-of-hidden-histories-john-heon/