Under a political zeitgeist agitated by the thralls of Western imperialist history, Power/Play, the new group exhibit at Twelve Gates Arts, investigates which experiences of South Asian children – raised in the arms of propaganda, occupation, and multi-polar media – get to be humanized. Through mixed-media pieces, video installations, paintings, and ceramics, the works careen around the subject and its specific aesthetic in a journey from childhood to adulthood to the complicated, politically charged space in between.

With works by Sophia Balagamwala, Noormah Jamal, Jagdeep Raina, and Hardeep Pandhal, Power/Play is curated by Ambika Trasi. It is an exhibit comprised of artists who all identify with and come from diverse and politically informed South Asian backgrounds, reflected in their practices.

The exhibit as a whole functions is as informative to an audience aware of its milieu as it is to a visitor engaging with the artwork without that foreknowledge. On first impression, the entire exhibit glows with the hues of pinks, baby blues, and yellow, with animated figures whimsically suggesting a more sophisticated sentiment behind their cartoonish exteriors. The artworks’ appearances are childlike not just by coincidence, invoking tender and innocent imagery at first glance, without seeming innately petulant and juvenile.

Balagamwala’s paintings, like in the piece “Boundary Commission,” depict an amalgam of headless or faceless men over meeting tables wearing jubbas and men’s shalwars, the traditional Pakistani tunic garment, or with their hands crossed behind their backs. These images resemble the many headless adults we grew up with in children’s cartoons, like in Powerpuff Girls in the West. In other paintings, in a similar bright palette, Balagamwala experiments with crushed velvet and other materials often dishonored as “informal” for their synthetic and common crafting quality. The artist “ruins them” intentionally with water- and oil-based paint, to make cartoonish faces. In one of her video installations, “Whereabouts Unknown”, the artist uses stop-motion and 2D animation to share an announcement of an artifact stolen during the colonial period being returned to the Karachi museum. Through Balagamwala’s paintings, she envisions a curious and wondrous investigation into the works of Pakistani political processes. Through her gaze, she stirs incitement to political action rather than boredom of these very adult-like happenings.

Raina and Pandhal’s video installations continue to guide a visitor unfamiliar with the symbolism behind the artworks. In Raina’s installation, “Chand Bagh”, a narrator maps the history of a Phulkari Bagh, an elaborate Punjabi women’s shawl that roughly translates to “garden,” comprised of intricate flower embroidery work, dyed with inks or dyes from flowers and vegetables, to depict Punjabi life. In the camera footage, the speaker guides the viewer through kaleidoscopic swatches of generationally safeguarded Phulkari Bagh threatened to be erased from family histories through the passage of inheritances and time. Fantasmic stop motion animation provides more background about the garment, and the viewer gains a history akin to a placid PBS informational special geared toward older audiences and children alike.

Pandhal’s video installation, “Happy Thuggish Paki,” takes a more whimsical tone, with a distinctly British accented voice freestyle rapping about British South Asian stereotypes; about violence and paradigms of terror, over an animated sensationalized PC game of Osama Bin Laden’s Abbottabad bunker with early 2000s anime girl faux ad pop-ups. Both video installations, one art historical and one tongue-in-cheek, toy with the gravity of ancestry and childhood and explore the depths of innocence. Raina’s piece examines the technical qualities of Phulkari Baghs as geometric and anthropological while sharing knowledge, and Pandhal’s piece opens a more satirical door into what it was like to grow up in the early 2000s in a world of early PC games and the Afghanistan War-era anti-South Asian jeers.

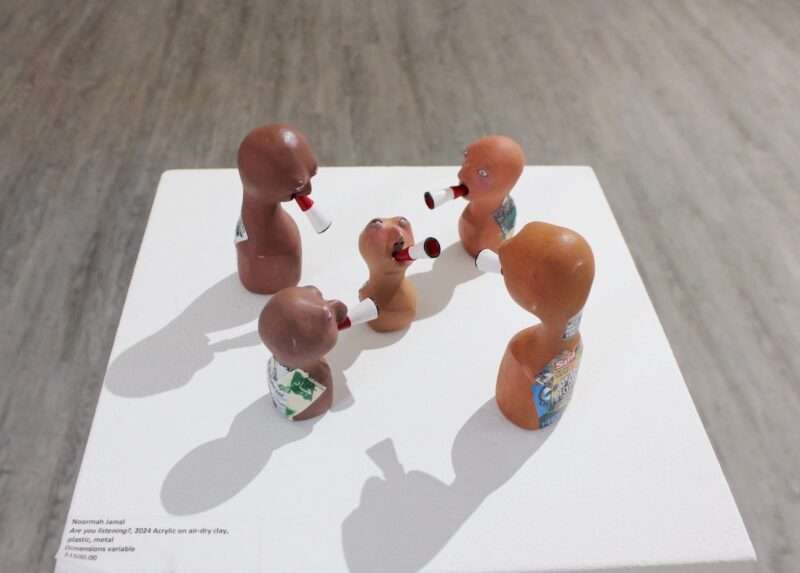

The knowledge and slices of life this exhibit invites the viewer into will stir curiosity and anger equally in the gut of an informed and uninformed viewer. Noormah Jamal’s pieces are emblematic. While also informative and visually stunning, Jamal’s paintings, video installations, and ceramics provide clues about Indian-Pakistani political relations, western imperialism, and South Asian girlhood. In her painting “When at Home”, two red-hued girls with nimbuses of flagrantly short hair gaze into the distance under a short rug. Enveloped with red, white, and blue with some glimmering golds, one girl, with laser-like brushstrokes from her vision, has flames coming from her skull.

Jamal’s work represents South Asian girlhood as chimeric, hairy, and unbecoming, as as creature with the acumen for the colonial and racial violence they have and will face in the future. South Asian girlhood is often for these reasons labeled indigestible for a white Western audience, and Jamal illustrates this concept through the color motifs in her paintings and the feathery, hair-like brushstrokes that make up even the stern unibrow on the older girl in her painting.

In another set of Jamal’s paintings, six stoic newscasters in separate paintings stare forward at the viewer like in an evening broadcast. On second glance, the paintings reveal layers upon layers of their depth: a figure resembling an Indian news anchor is depicted with symbols of conspiracy to reference a recent hoax of a Pakistani spy pigeon in India. A figure with a neutral gaze is surrounded by images of cultural symbolism like a headless fish to allude to the lack of comprehension in news stories. A figure wears a loose hijab. A figure bearing resemblance to Bill O’Reilly fades dark like an old television monitor turning off, the piercing blueness of his eyes a symbol of whiteness and American surveillance. Jamal’s artworks continue to raise questions of the relative ineptitude expected of children versus the political messages, ancestral strife, and the grief that South Asian children and other children have known since birth. Balagamwala’s “Whereabouts Unknown” touches on this same concept, exploring the indoctrination of youth into the colonial narrative of innate power.

As many artists try to reimagine what it felt like to be a child, desperately chasing what they are not afforded in their lives including the tender thrill that is coming of age, Power/Play responds to those Western milestones by guiding the viewer through a journey that argues for the personhood of children. Many South Asian children, through the existence of cantankerous national politics, ominous geopolitics, and racism, are privy to the gravity of their existence by the time they can touch their great-grandmothers’ shawls or grip a paintbrush. Power/Play rivetingly illustrates this concept through an exhibit that is as aesthetically flamboyant as it is educationally daring, putting a curatorial microscope on the deeper systemic issues that make up what it means to be a South Asian child living today while inheriting centuries of violent history. There are many exhibits by South Asian artists that, from their subject matter, sentiment, and subsequent review, are made to educate or enthuse a majority white audience. This is an exhibit, for the same reason, that a visitor can tell was made by a South Asian artist for other South Asians to feel seen and to remember a childhood they have known their whole life.

Power/Play is on view at Twelve Gates Arts until May 18, 2024. Please visit their website for more information on their hours and location.

Read more reviews by Vriddhi Vinay on Artblog.