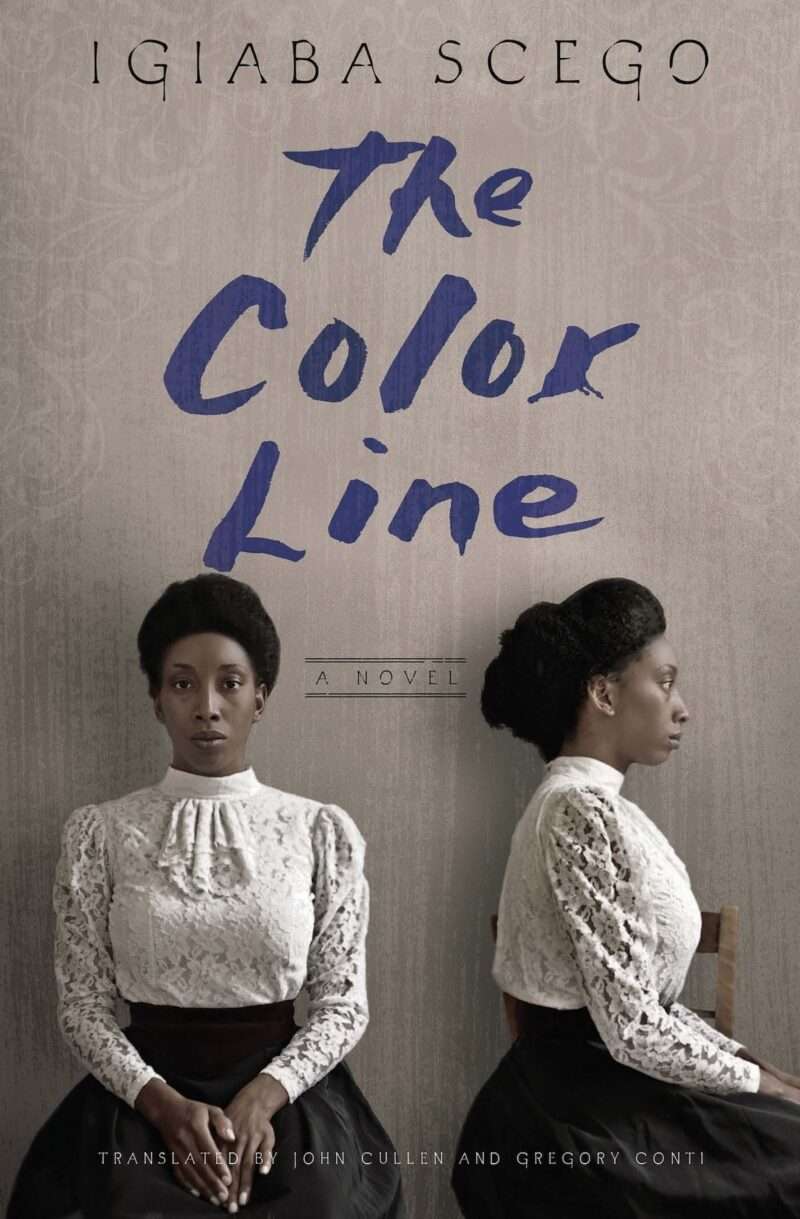

Igiaba Scego’s unputdownable novel, “The Color Line,” familiar and haunting, touches both my artist’s soul and Black art archival spirit. It draws me in with its rich, considerable attention to two marginalized women in their forties existing over one-hundred-years apart. Lafanu Brown, a gifted Chippewa and Haitian expatriate painter lives in nineteenth century Rome. In the present, Leila, a contemporary Somalian curator digs through archives to find the traces of Lafanu’s existence.

Lafanu is a lightly fictionalized depiction of Edmonia Lewis (1844-1907), an African American and Mississauga Ojibwe sculptor from Rensselaer County, New York who lived abroad and stated, “I was practically driven to Rome in order to obtain opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.” Lafanu’s character also incorporates the life of Sarah Parker Remond (1826-1894)— an expatriate lecturer, abolitionist, and activist from Salem, Massachusetts who extensively traveled with Frederick Douglass and her brother Charles Lenox Remond, advocating against slavery and promoting feminism. She moved to Italy, became a physician, and married a Sardinian office worker.

In her book, Scego combines Lewis and Remond’s possible American experiences and does not sugarcoat the challenges of racism, sexism, and classicism. During her upbringing in the Chippewa tribe, Lafanu imagines traveling the world in a similar fashion to her absent Haitian father. Her community always pins Lafanu against Timma, her younger, fairer-skinned sister. Once privileged abolitionist Bathsheba McKenzie sees Lafanu’s promising artist’s skills, Lafanu becomes a protégé taken under the wings of a kind benefactor (with a personal agenda). Lafanu enrolls at Coberlin (a thinly disguised Oberlin), one of the first American colleges accepting her race. The experience proves to be vitriolic as blatant disrespect is piled high on Lafanu. She faces turmoil and disgrace, worsening after an angry mob encounter— which at the time were orchestrations meant to keep segregation thriving.

Although a traumatized Lafanu is eventually booted out and forced to return to an uncomfortable situation, her determination to become an artist topples all else including the famous orator Frederick Bailey (a play on Fredrick Douglass) attempting to seduce her away from her purpose. Her eventual departure to Rome is an escape from American ridicule. Yet, Italy too has those harboring ill will and displeasure regarding her presence.

Still, her talent grants plentiful commissions and modest respect.

Her studio ultimately brings her solace.

“Lafanu herself, even in the frenzy of her professional commitments, from time to time yielded to the nostalgia game and managed to revive with her brushstrokes the rituals of that lost world. She showed no pity in her portraits, however. She remorselessly depicted a society in decay, a society that had not resigned itself yet to the new wind of the nineteenth century…. It was so bizarre for a woman with black skin to be a painter that people wanted to touch such an oddity with their own hands.”

Meanwhile, Leila, a modern-day curator, represents the countless Black women art historians and archivists existing today. A first-generation Italian descendant of parents from Mogadishu, Somalia, Leila studied at Rome’s Università La Sapienza, one of the world’s oldest institutions and the largest in Europe. Leila follows the curatorial footsteps of Dr. Samella Lewis and Dr. Regenia Perry, the first Black women to earn doctorates in art history. She’s committed to uncovering lost Black stories sunken far below the prevalent white art historical canon— Black stories otherwise bound for erasure. For example, talking to a friend near the white marble “Four Moors” Fountain, Leila internalizes the problematic nature of the four chained nude women, refraining from disclosing her discomfort. This conditioning to withhold true feelings mirrors Lafanu’s own passivity. Leila has every right to address the heinous artwork, but it’s far easier to keep those opinions to her research.

“In my profession, I was paid to generate ideas, and so I did, one after another, not always on the subjects I found interesting. But now there was Lafanu… her portraits, her landscapes. A Black woman who had chosen, through the sheer force of her will, to be not just free but a free artist in a time when women in general weren’t free at all….

It’s such a shame that no one knows about Lafanu.”

Leila finds a likeminded comrade in Alexandra, an intelligent, resourceful American professor that Leila meets at a colleague’s wedding. They hit it off tremendously, bonding over the problematic Four Moors Fountain and exchanging research notes on the mysterious Lafanu. They hope to bring the few Lafanu paintings that were rescued to the Venice Biennale. Another affectionate camaraderie that Scego explores with delicate precision is Leila and her twenty-year-old cousin Binti. For seven years, their relationship has been a series of letters, social media messages, and phone calls. Things become perilous when Binti makes the rash decision to travel to Sudan alone. Leila’s desperate search for more information on Lafanu happens alongside Binti’s sudden disappearance. Leila’s duel agony and Binti’s eventual return deliver painful blows. These graphic moments unravel the stark depth of how women’s bodies— instruments of revenge and objectification— remain at war with global patriarchal systems. Yet, as Binti’s family find difficulty in adjusting to her damaged mentality, Leila makes it her business to help.

Scego’s language usage is as detailed as a sophisticated painting, sharp and vivid, incorporating art history and a keen writer’s imagination together. Also, she moves in and out of sequence, taking great liberty with time, creating an interesting rhythm. Italy’s setting is an essential backbone to two people who will never meet. Lafanu’s voice is told in a third person point of view, encouraging us to watch her from the outside, look in on her as she paints. Coincidentally, she is writing a letter to her Italian fiancé, stating that her story can be better told in paint. Whereas on the opposite end, Leila’s first person account divulges her isolations as a curator separated by her poor upbringing and a Muslim religion most do not try to understand.

Moreover, art and art history act as central healing vessels for its revolutionary women characters. Lafanu escapes her volatile past through painting and is celebrated for it. Leila exhausts all resources to obtain a full scope of Lafanu’s artistic life while simultaneously freeing Bintu from painful oppression.

“The Color Line” provides a provocative glimpse into often romanticized Italy. Lafanu and Leila’s stories unveil an unsettling place still steeped in public art that offends them, an unprogressive culture that includes them little by little. They have to fight to carve a notch, some notion of validation and grace. An ideal read for history scholars or painters or complex multi-disciplinarians (artist-scholars do exist), the novel closes on Igiaba Scego’s contextualized endnotes on the Italian statues that compelled her to look into Black artists. These intimate sketches imagine Lafanu and Leila embarking on similar paths, gazing at these chained figures, whispering to the stone ears, “I know how you feel.”

Awarded a translation grant by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, John Cullen and Gregory Conti translated Igiaba Scego’s “The Color Line,” originally published as “La linea del colore.”

Read more by Janyce Denise Glasper on Artblog.

The Color Line

A Novel

by IGIABA SCEGO

Translated by JOHN CULLEN

Translated by GREGORY CONTI

Paperback $19.99

Purchase at Other Press