PART ONE: The Venice Biennale

We’ve been to several Venice biennials since 1993, and this year’s strikes us as one of the best we’ve seen. Curator Adriano Pedrosa put together an exhibition that is reasonably coherent and more expansive than most, highlighting artists from around the globe who are not just “likely suspects.” Among them is Jeffrey Gibson, a Choctaw/Cherokee artist, who was chosen by the U.S. for its Pavilion. His installation highlights his native heritage and history through blending traditional and contemporary media. This marks the first time a First Nation artist has been so honored by the U.S., and for that reason the choice has received much media attention in the States.

Wael Shawky’s contribution to the Venice Biennale as Egypt’s representative has received far less attention in the U.S. media, but deserves better, especially given the Philadelphia connection. He received his MFA in 2001 from the University of Pennsylvania, was a visiting professor in 2016.

Shawky was born in Alexandria, Egypt and, after a period in Saudi Arabia, earned a BFA from the University of Alexandria before coming to the University of Pennsylvania in 1999 for his graduate studies. After his faculty stint at Penn he moved back to Alexandria with his family, but still maintains a studio in Fishtown.

Shawky’s film, Drama 1882, was commissioned for the Biennale by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture and the Italian Accademia d’Egitto, and it was an enormous undertaking. Operatic in scope, it involves dozens of performers, a powerful musical score, choreographed dance-like movements, theatrical set design, and elements of animation It was shot on an actual movie sound stage in Cairo. The film masterfully confronts the intricacies of colonialism in a brilliantly layered and nuanced manner.

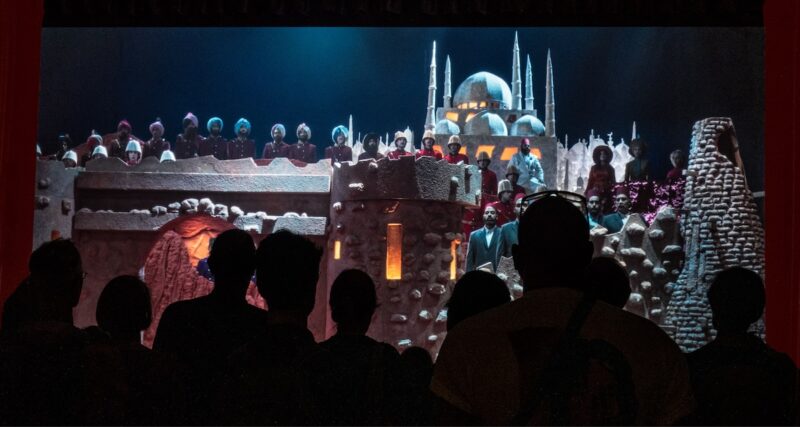

To get to the projected film in the Egyptian pavilion, visitors first enter through heavy, green velvet curtains (and wait for their eyes to adjust from the bright Venetian sunlight to a darkened room). To the left, a series of sculptures made from a range of materials begins to emerge, the largest of which is an eerily striking but enigmatic form. Seemingly fashioned from packed earth (we were unable to find any labels), it resembles a type of hermit crab carrying some sort of domed structure. Its implied motion points towards the projection screen across the room.

A sizable crowd, clustered in front of the wall-sized screen, was transfixed by the operatic performance framed by red velvet curtains. In the film, a cast of characters is set against a surreal backdrop of an imagined multicolored landscape and stylized, ghost-like buildings. The characters are dressed in period clothing from a mix of cultures. They sing to each other in classical Arabic, swaying back and forth in exquisite synchronized motions.

Shawky relies on visual, aural and kinetic seduction to snare his audience. Although the historic figures are identified, the film is not a documentary but more a filmed performance of an opera. and as with Verdi’s Aida, and it doesn’t really matter if a viewer knows the history of Egypt. Rather, it is a poetic work that attempts to explore, in the artist’s own words, “the gaps between fact and myth in history.” Drama 1882 could have been set anywhere on the planet and even in the current year (and renamed Drama 2024). It is a metaphor for the human condition. When a group of voices chants, “we were full of hopes . . . but deceit broke Urabi,” we all understand.

Two University of Pennsylvania art professors whom we contacted, Jackie Tileston and Joshua Mosely, overlapped with Shawky in 2000 when he was an MFA student. According to Tileston, his thesis sculpture, a room-size airplane made out of 2x4s, was a standout. Mosely described Shawky as “phenomenal,” and played a role in inviting him back to Penn to teach.

We didn’t get to see Shawky’s companion exhibition, I Am Hymns of The New Temples at the Museo di Palazzo Grimani. However, Lisson Gallery has posted a great interview with him that discusses both shows.

Entering the Central Pavilion to view Kay WalkingStick’s paintings was a very different experience. The grand, well-lit space houses hundreds of artworks, and trying to find the location of a specific artist is a challenge. Unlike past biennials, there is no longer a printed map. Instead, viewers are expected to navigate via an online site using their phones. We recommend cornering a staff person and asking them for directions!

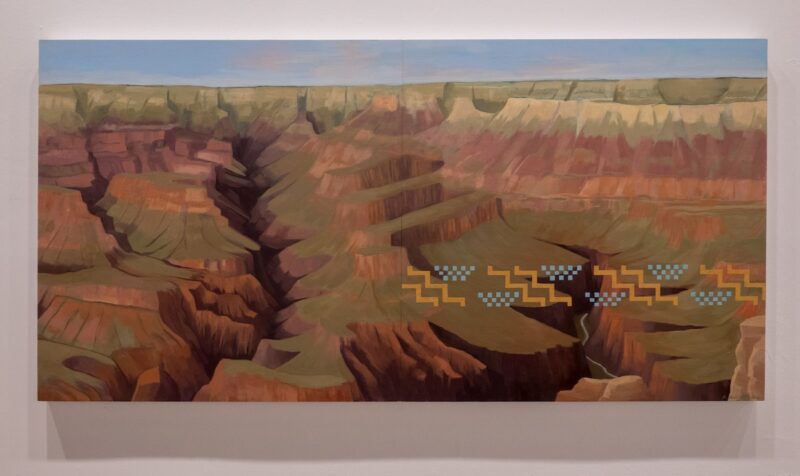

Against this challenging backdrop, arriving at WalkingStick’s exhibition provided a breath of fresh air. Three adjoining walls are graced by a series of beautifully rendered landscape paintings of the Grand Canyon and other lands of the American West, overlaid with the traditional designs of the indigenous people who once inhabited the area or whose remains lie there now. Like Shawky, WalkingStick confronts painful multilayered histories, but she does so in an understated manner requiring quiet contemplation. Her paintings ask us to imagine new modes of coexistence.

WalkingStick’s background itself can be termed an experience in coexistence. Her mother was Scottish-Irish, while her father was Cherokee (and could write and speak his native language). After her parents’ divorce, WalkingStick spent most of her artistic career investigating her cultural heritage. Having been raised largely by a single mom, she has also been a steadfast feminist, having been named an Honorary Vice President of the National Association of Women Artists.

Now a Professor Emerita of Cornell University, WalkingStick is getting the attention she deserves . . . at the age of 89 (vying with Philadelphia’s Anne Minich!).

PART TWO: Verona, Parma, Rome and Sardinia

Verona

We are always on the lookout for new, interesting and/or unusual art venues that might be of interest to Artblog’s readers. Some of these are quite surprising. (See map for the location of Italian cities mentioned below.) While we were in Verona we happened to come across a new art exhibition space in, of all places, an Eataly! (Yes, that “temple of food” that has three locations in downtown Manhattan and branches across Italy and the U.S.– including one coming soon to King of Prussia Mall.) Called Eataly Art House (E.A.R.T.H.), it is a 3,300 square foot professional exhibition space mounting temporary exhibitions of contemporary art, about six a year. It sits above a typical Eataly, with its vast array of gourmet food items and high-end restaurants. Its mission, as stated on their website, is “to create new ways for the public to experience art and a new way of collecting.”

The two most interesting exhibitions on display were Premio E.ART.H., a group show of 10 artists concerned with sustainability (the artists were selected via a competition sponsored by Illy coffee) and Terre Fragili by Pierluigi Slis (whose collages are reminiscent of the work of former Philadelphia artist Cindy Back, who now lives in Portugal).

The Verona complex is actually a former cold storage warehouse (or frigorifera) built in 1930. We couldn’t help but think of the Crane Building’s Icebox Project Space.

Parma

In the vicinity of Parma (famous for its prosciutto and cheese) we had a truly transcendent art experience in visiting the Fondazione Ettore Guatelli. This museum occupies a complex of buildings that had been the home and farm of the Guatelli family. Ettore was born in 1921 into this family, which had moved onto the farm as sharecroppers but was eventually able to purchase it. He was apparently the frailest among his brothers and thus was allowed to study and, eventually, become a primary school teacher. His passion, though, was the lifestyle and material culture of the rural people of the area, and he began collecting items of all sorts with an eye to preserving them for posterity. He eventually amassed more than 60,000 artifacts including tools, hardware, furniture, toys, clocks and kitchenware. (Think of Henry Mercer on steroids.) What really sets his collection apart, however, is the way he chose to display it. Almost everything is hung on a wall or on the ceiling, in dizzying, repeating patterns of like objects and forms.

The museum is not just a local oddity; it has been lauded by artists, critics, writers and filmmakers such as Christian Boltanski, Vittorio Sgarbi, Roberto Benigni and Bernardo Bertolucci — who borrowed several thousand of Guatelli’s objects to use in the filming of “1900.” It is not easy to visit: there are very limited hours and you must reserve a place in advance because entry is by guided tour only.

Rome

No art visit to Rome would be complete without a stop at the MAXXI (Museum of Art of the 21st Century). Its current, blockbuster show is Ambienti 1956-2010: Environments by Women Artists II. Building upon a project by the Haus der Kunst in Munich, it is a survey of 18 women artists from around the world who were instrumental in creating “immersive works.” (Given that visitors will be walking through often fragile installations, they are required to leave personal belongings in the cloakroom, remove their shoes and wear only socks or museum-provided foot coverings while in the galleries.) Notable works include Aleksandra Kasuba’s massive, walk-through color labyrinth, “Spectral Passage” (1975); Judy Chicago’s “Feather Room” (1966-2023), which managed to distribute individual feathers throughout the museum); Esther Stocker’s op-art, geometric space referencing the German philosopher Gottlob Frege (2004-2024). Of course, architect Zaha Hadid’s MAXXI building itself — a colossal piece of immersive art — is included as one of the 18 featured installations.

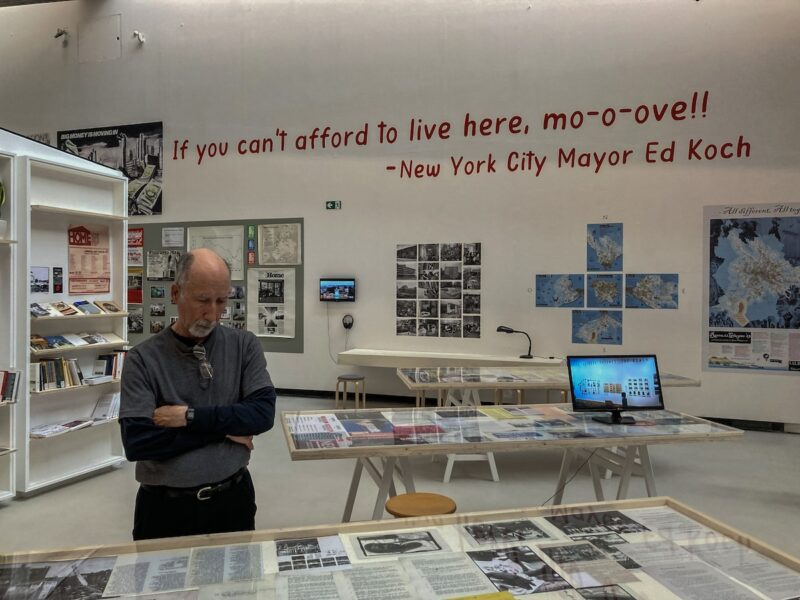

A wonderful surprise was the inclusion of a work by Martha Rosler, “If You Lived Here . . .” (1989 – ongoing). Rosler is a Professor Emerita at Rutgers. True to the artist’s approach, hers was the most direct and politically engaged work in the exhibition. (She collaborated with a number of Rome-based artist-activists in updating it for the MAXXI.)

Sardinia

Finally, Sardinia. In a way, the entire island is a museum with thousands of archeological sites including, most uniquely and most impressively, massive human-made stone structures called nuraghe. Functioning as domiciles, tombs, fortifications and religious sites, they date back to the bronze age. In their scale and their graceful simplicity, these structures outclass any of the earthworks made by contemporary artists like Smithson, Heizer, Judd or Turrell. At some of the sites, they have been partially rebuilt and/or stabilized, allowing visitors to climb up and into them. The Sacred Well of Saint Christina, the Nuraghe Losa and the Necropolis of Sant’Andrea Priu are absolutely humbling.

Humbling as well, is realizing how selectively we artists have been taught. Art history texts have long presented the Venus of Willendorf as “one of the world’s oldest and most important surviving works of art.” Many similar objects have been found in Sardinia, and the national archeological museum in Cagliari estimates their ages to be contemporaneous with, or even older than the famous statuette in Vienna!

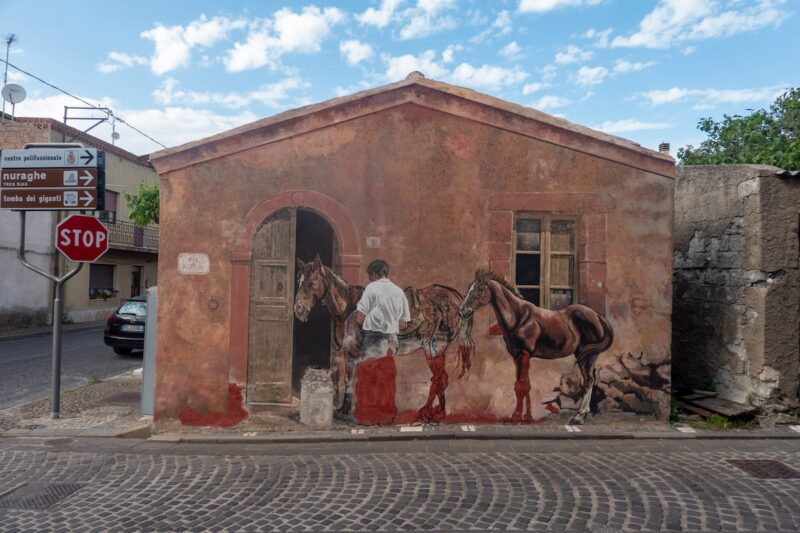

One last destination for us in Sardinia was not an archeological site. It was the small town of Tinnura that has sponsored an impressive public art project featuring dozens of very well painted murals and a beautiful fountain done in tiles whose water flows through the mouths of ceramic zodiac symbols (producing an exuberant sound). The town, of just 268 residents, undertook the project under the guidance of its mayor, who is also a medical doctor. They invited Sardinia’s best-known muralist, Pina Monne (who just happens to live in the town!) to do five murals and then opened it up to other artists. The murals are sensitively done and incorporate the architecture and history of Tinnura, which may now be Sardinia’s foremost mural city. Another parallel with Philadelphia, perhaps?