Josh T Franco, the artist curator of Where I learned to Look: Art from the Yard at the Institute of Contemporary Art, grew up seeing his grandfather build annual, outdoor altars in the garden of his Marfa, TX home. Franco is also an art historian, so was challenged by his town’s proximity to the house, studio, and foundation, Chinati, that Donald Judd established in Marfa, which has turned the small, Southwest Texas town, where the train no longer stopped, into an international, art pilgrimage site.

Franco approached the exhibition as a way of thinking about the relationship between a vernacular art form created by working-class individuals as an extension of their personal, domestic spaces and Donald Judd’s large-scale project of siting his own work and that of artists he respected within and adjacent to his home, studio, re-purposed military buildings and outdoors.

Exhibitions that explore ideas face a high bar for making convincing arguments, and Where I learned is best approached as work by a number of artists whose relationship to vernacular yard art are varied, rather than as a tightly-organized proposition.The artworks will certainly interest a broad audience; they are intriguing, thoughtful, visually arresting and in some cases, great fun. It’s just right for a summer outing.

The exhibition opens with Franco’s installation from which the exhibition takes its name. On the floor is an arrangement of votive candles set on a semi-circular bed of gravel, bordered by tires cut in half to create a decorative edging. It provides entree to his grandfather’s garden, which is the subject of the video projected on the back wall. The video’s overwritten narrative is in both Franco’s voice and that of the Virgin of Guadalupe, to whom his grandfather’s altar is devoted. She compares the response of Franco’s family and friends to her altar with those of the visitors drawn to Marfa by Judd’s work; the family members bring her offerings, she says, while the Chinati pilgrims take photos. Franco himself has a foot in both worlds.

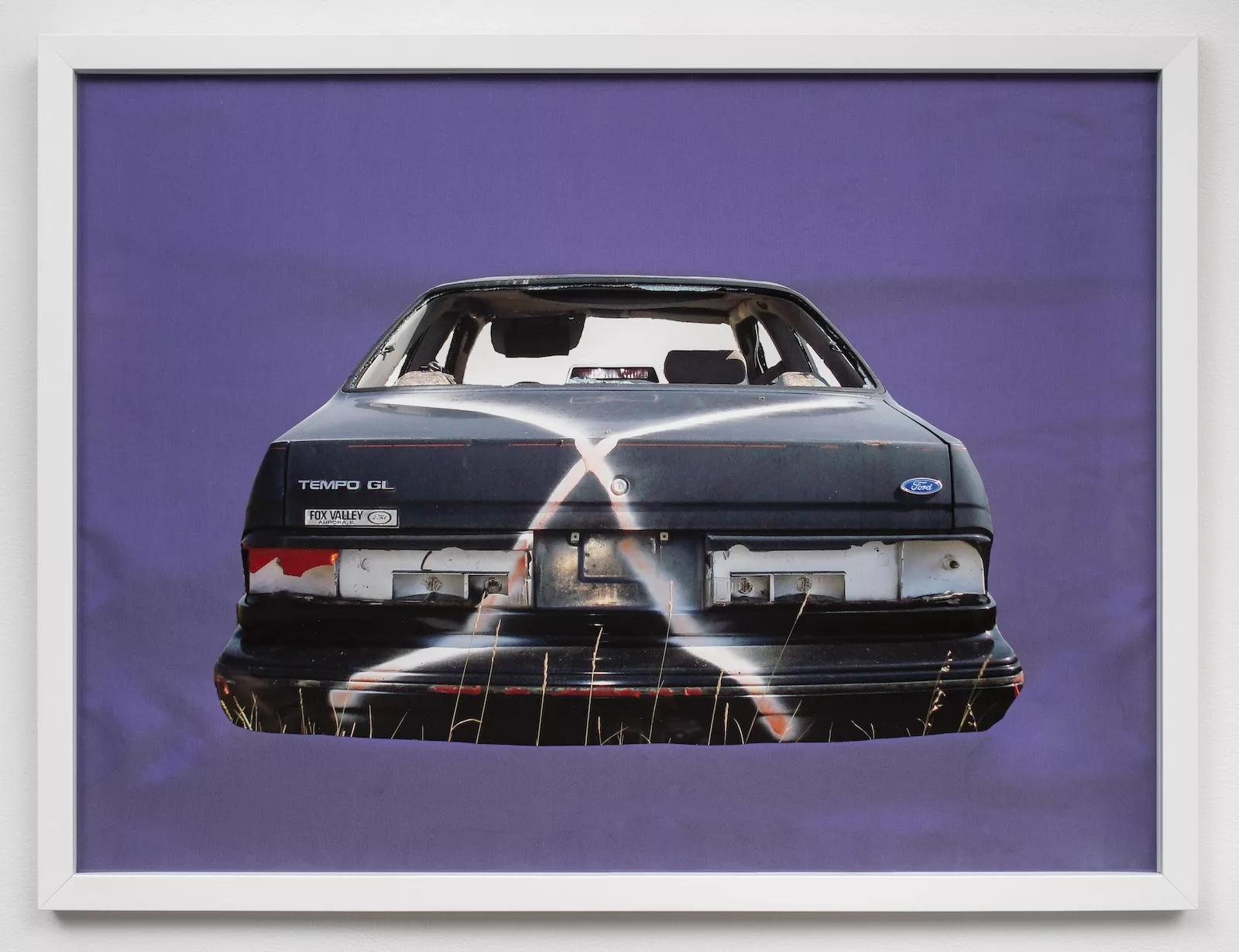

The assembled works by self-taught and academically taught artists fall into various categories. Several, by indigenous artists and artist collectives, deal with ancestral relationship to land, which provides them sustenance, and with their living conditions on that land, which are circumscribed by outsiders. The long film by Brian Jungen and Duane Linklater, “Modest Livelihood” (50 min) contrasts the artists’ careful and respectful subsistence hunting (the title cites a Canadian legal judgment defending their hunting rights) with the spoilage of settler mineral extraction. Wendy Red Star’s series of photographs “Rez Pop K, J, E, G” shows obsolete car models, abandoned on reservations; they have become part of the indigenous environment because they have no value as junk and the communities lack the means to remove them.

Another group of works honor familial and cultural heritage as expressed within the landscape. Photographs show the artist and art historian, David Driskell, in his garden with a bottle tree. Bottle trees reflect African folk beliefs and traditions that Driskell acknowledges he doesn’t subscribe to, but he honors the memory of his ancestors with the tree.

The photographs lead into an extraordinary triple altar by vanessa german, “nothing can separate you from the language you cry in,” which sits upon bases constructed of masses of blue bottles, of the sort Driskell used sparingly. The dazzling upper levels consist of scavenged and assembled decorative objects from domestic interiors (mirror, clock, porcelain birds and figures in period dress, and an abundance of gilded flowers). This accumulation of found objects refers to African power figures and their heritage in African diaspora communities in the U.S. and Caribbean. Allison Janae Hamilton stages performances in the North Florida landscape that refer to African traditional stories, and displays signs and assembles palm branches, in reference to those she has seen on the roadsides of her neighborhood.

Some of the artworks have fun with the idea of personalizing their immediate environment. The most prominent is Clarke Bedford’s extravagantly-decorated VW Bug which is one of six, similarly-appointed vehicles, all drivable, that normally sit outside his equally-decorated house in Maryland. The car is entirely encrusted with scavenged objects that began life as hardware (chain link, gears, springs) or shiny and decorative, primarily domestic items (crystals from chandeliers, mother-of pearl door pulls, silver-plated statuettes, shards of broken mirrors). My favorite is the silver coffee pot sited as a hood ornament; a delightful alternative to the conventional ornaments that advertise speed.

Finnegan Shannon produced a game that involves tossing hoops, as well as two functional cornholes on the ICA’s outdoor terrace; a painted wall at the back has text that suggests the value of having fun. Sitting at the far end of the terrace, the games invite visitors outdoors – which will be more welcome when the heat waves pass. Perhaps the curator is suggesting a relationship between back yard play equipment and yard art.

Back in the gallery, sited between Bedford’s car and a bench by Donald Judd (itself placed in front of a video by the BUSH Gallery (collaborative), Jeff Koons’s “Gazing Ball (Birdbath)” is in danger of being overlooked, which is an irony on multiple fronts. Koons’s work usually attracts all the attention he might want, and he has created work in the spirit of yard art, such as his enormously-popular “Puppy”; but this joke, an expensive artwork that is a plaster copy of a mass-produced item you might buy at Walmart, concerns the opposite, in both subject and execution, of the hand made and individually-driven spirit of yard art.

Several artists are represented with slight works that need more back story than they are given to connect them to the exhibition’s theme. Small, wall-hung pieces by John Outterbridge and Noah Purifoy, who were part of an L.A. African American art community in the 1960s, give little idea of the more public dimension of their work. Purifoy’s art grew out of his experience with Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, the most notable, large-scale vernacular sculpture in the U.S.; although public, the towers align closely with the spirit of yard art. Purifoy used the site for community teaching, and after rebellion in Watts, gathered debris which he turned into “junk art.” He eventually moved into the high desert of Joshua Tree, where he created a large, outdoors environment around his own house. Outterbridge intentionally combined “poor,” scavenged materials to create art that spoke to African material and cultural heritage and African-American experiences of displacement, make-do housing and determined personal expression as seen in yard art. He likened his art made from rags to soul food, made from scraps.

Three photographs from Beverly Buchanan’s archive sit on the wall above a flat display of photographs sent to her that document Tyrone Guthrie’s Heidelberg Project. Guthrie began to clean up abandoned houses and vacant lots in his old neighborhood in Detroit in 1985, and over a period of time he added junk sculpture and worked with local children to turn the entire neighborhood into a space for art.

Buchanan’s sculptural work sited modest stone assemblages that looked like building ruins, on public land and in cemeteries in locations with significance to African American history in rural Georgia. She is best known for small sculpture based on country shacks she had seen in rural, African American communities.

The exhibition also includes works by José Esquivel, Hipolito Polé Hernandez, Donald Moffett, Rubén Ortiz-Torres, and the Painted Screen Society.

If the term “Yard Art” is unfamiliar, outside of ads for pink flamingos and decorative bird feeders, it may be because the work it describes rarely shows up in galleries or museums, and then only in the form of fragments or documentation. A cover article by Gregg Blasdel in “Art in America” in 1968, and an exhibition he co-curated at the Walker Art Center in 1974, gave Yard Art the art form a prominence that it has never regained, despite the greatly increased museum exposure of portable works by individuals beyond the formal art world, who are variously termed “self-taught,” “visionaries,” or “outsiders.” Blasdell wrote about the elaborate environments they built adjacent to their homes. These were expressions of personal vision and imagination; some had a religious motivation. Their execution involved extraordinary amounts of work over years of construction, and included a great deal of scavenged and re-purposed materials by necessity of the artists’ poverty and/or isolation.

Where I learned to Look: Art from the Yard, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania through December 1, 2024

Read other coverage of the ICA’s exhibitions on Artblog.