Theatre of the Everyday

by Marianne Bernstein

Limited edition, $60

First edition of 200 / Numbered & signed

Printed in Milan, Italy

ISBN: 9-79-8-218-3231-3

This large format monograph spans the career of Marianne Bernstein over 40 years and creates a tasteful venue for experiencing Bernstein’s photography. Kudos to studio FM milano for their striking design work.

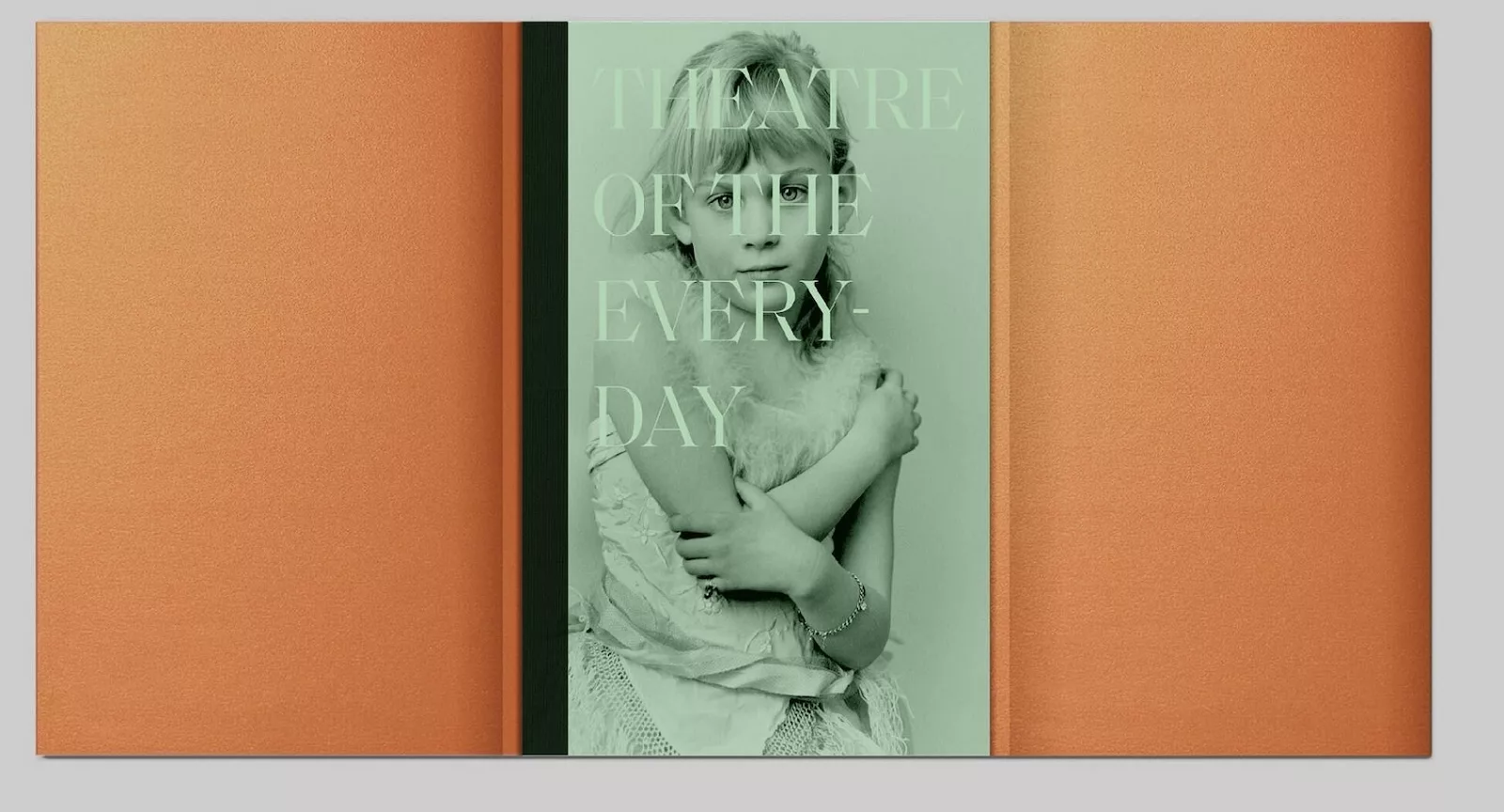

The locations range near and far: Philadelphia to Iceland, Mexico to Chicago, New Haven to Sicily, La Jolla to Taiwan, to name a few. The 190-plus pages are bound in copper metallic cardstock that wraps around in a double fold. Open the cover and another copper flap awaits, listing the section titles. Open that and the cover becomes stage wings. In the center area a light green monochrome portrait of a young girl playing dress-up gazes at us through the overlaid words, THEATRE OF THE EVERYDAY. A curious title that distracted me as I looked through the photographs, it seemed to impose a particular interpretation on this survey of Bernstein’s work, but I wasn’t sure what. Does it imply that everyone becomes a performer in front of a camera? Does the image frame turn rooms and landscapes into sets? Do the objects of life become props? I thought of Brecht and the way he sought collaboration between the playwright, performers, and audience. Like Brecht breaking down the fourth wall to remind audiences that they are watching a presentation of life, not actual life, perhaps Bernstein’s reference to the theater is a declaration of photography’s artifice, its subjectivity. The photographer is always present, always making choices.

The book includes an artist’s statement and essays by Gregory Volk, Kelsey Halliday Johnson, Stan Mir, and Raimondo Cortese about Bernstein’s life and work. These texts provide insight into her activities as a curator and organizer of artists and communities, her film work, and her participation in artist residencies. An index at the back of the book gives more detailed information about each of the photos. It’s interesting to flip through the book then go back and read what are essentially captions in order to understand the groups of people that have stood, sat or lain in front of her lens, which sea we’re seeing, which lava field is glowing, which town a curtain hangs in.

The book is organized into six sections: “Ensemble,” “Notes,” “Trouble in Paradise,” “Intermission,” “Denouement,” and “Finale.” Within those sections, Bernstein plays with the flow of the images pairing and juxtaposing some, isolating others. She notes the influence of film editing and montage by the pioneering Russian filmmakers Lev Kuleshov and Sergei Eisenstein in determining the order of the images. In editing, the Kuleshov Effect explains how viewers’ perceptions may be influenced by pairing images together.

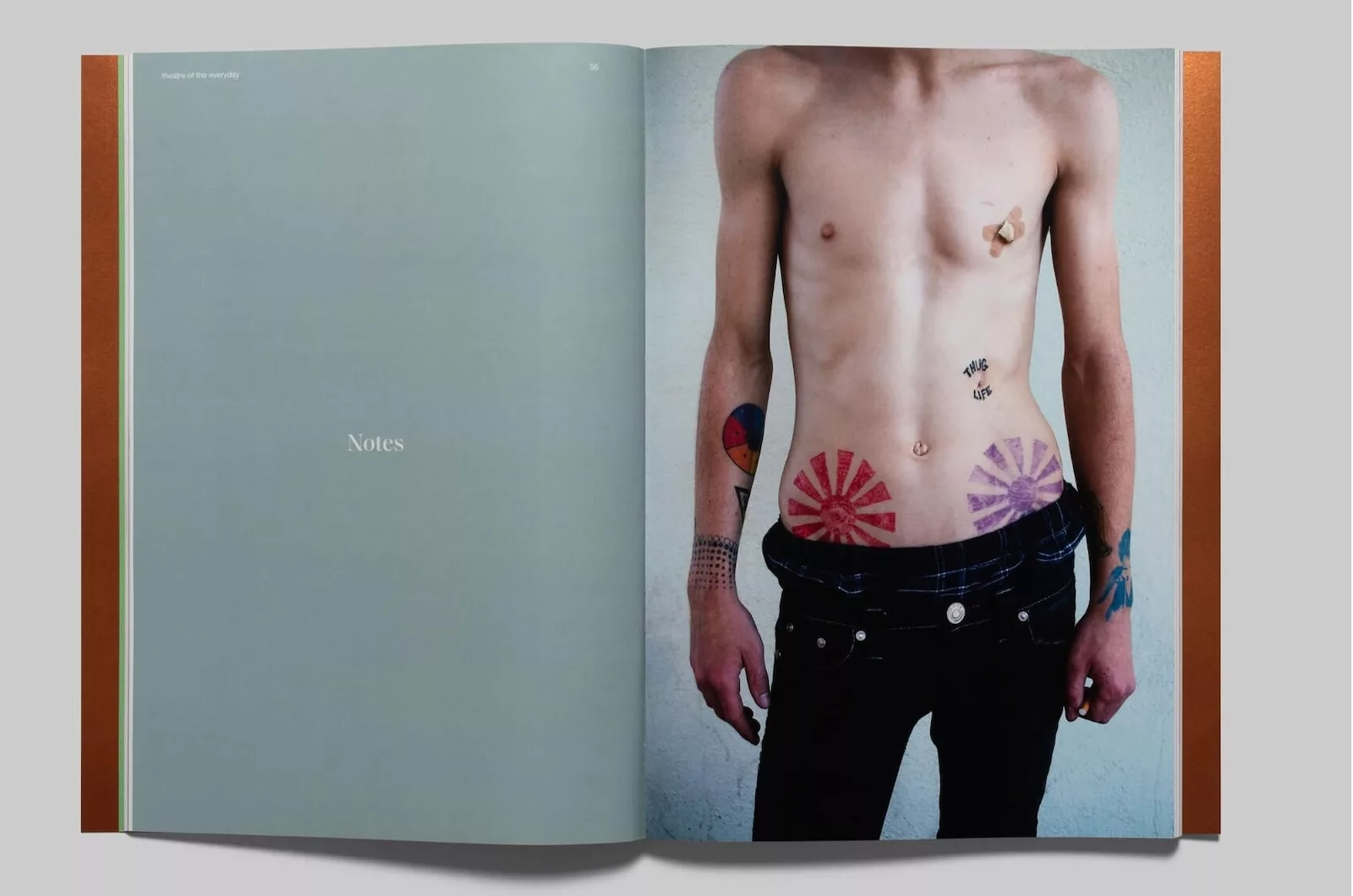

In the first two sections, “Ensemble” and “Notes,” we see mostly portraits of people from a range of socioeconomic groups and ages. Some are from a previously published work called Tatted, where Bernstein photographed strangers with tattoos that she met on South Street in Philadelphia. We see people from a soup kitchen in the Germantown area of Philadelphia, and inmates from Rikers Island prison in New York City. On two facing pages we see compelling portraits of an older woman and man. These two strike me as being characters. Maybe it’s the Kuleshov effect. The woman is Mariam McGlone. An early modern dancer who performed with The Humphrey Weidman Company then with Martha Graham. She fits the part of an aged dance pioneer beautifully. Dressed in black, dark hair pulled back to show angular cheekbones, her intensity comes through even sitting. She gazes off to the left past the shadow of a figure, which adds a touch of surrealism to the photo. On the opposite page is a portrait of Joe Sabatini. He is a 95-year-old veteran in a wide-brimmed Dudley Do-Right sort of hat. The strap sits under his lip rather than under his chin. His wheelchair has been placed on a backdrop for the portrait at the Veteran’s Hospital in New Haven. He meets our gaze with dignity, despite being in a robe and a hat at odds with the situation.

The section “Trouble in Paradise” conveys the fragility of life and the strength of perseverance, even if that is simply accomplished as an observer. We see an image of Bernstein’s mother on her deathbed paired with a broken mannequin lying prone and abandoned, a casualty of the riots and looting in Chicago after George Floyd’s death. A variety of dead fish from markets, a girl hugging a calf at a 4H fair, even a portrait of a “handsome rooster” takes on an air of melancholy. No one will be spared from the inevitable. And then there is the chaos of life to contend with. A double-page spread is filled with curly-fleeced Icelandic sheep crammed horn to eyeball within the frame. Another double-page spread shows stacks of empty boats with spray painted numbers: “93,” “88”, “56” and so on. Heaps of colorful life jackets are strewn on the beach below the boats. The index entry for this is: “Migrant boats and life-preservers during a summer of tragic mass drownings. Sicily (2023).”

In the sections “Denouement” and “Finale” Bernstein takes us outside into the elements. We see people immersed in waters around the globe, from Blue Lagoon, Iceland, to Quissett, Massachusetts. The dark waters of Reykjavik Harbor in the North Atlantic are contrasted to the sea glass green of La Jolla’s Pacific Ocean. The rising glow from lava fields play off the swirling colors of the Northern Lights. The book ends with a double-page aerial view of a landscape. Deep purple-colored veins and capillaries infiltrate variegated patches of dark greens, light browns, and smudges of red. Diagrammatic lines of white dashes stand out against the dark background. I don’t know what I am looking at or where it is, but the land is vast and I’ve never seen anything like it. The image wavers between abstraction and representation, even after I learn that the white dashes are sheep from the fall round-up in Thingeyri, Iceland. Once I understood that, I could almost make out their little feet. I think they are traveling right to left. No, now I think it is left to right. It really doesn’t matter. This happened in 2012. What does matter is that it’s a beautiful, mysterious moment of reality that Bernstein captured and now shares with us.

Marianne Bernstein will be signing copies of her books on Saturday, September 7, 2024, at the Photo Book Fair, part of the 20/20 Photo Festival, Cherry Street Pier, Philadelphia, PA.