A temporary exhibition drawn entirely from the permanent collection, Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes might not be showing anything ‘new’ – but it carves out space for perspective and discussion. Unlike last year’s blockbuster Manet/Degas exhibition at the Met, there are no paintings gathered from afar–nothing on loan from the Courtaud, borrowed from the Musee D’Orsay, or temporarily unearthed from unnamed private collections. For this summer exhibition, the thirty four iconic works on view in Matisse & Renoir have been relocated from their second story home to the galleries downstairs, placing the artworks in conversation. The dialog of the exhibition centers on mutual respect, artistic exploration and intergenerational mentorship – with none of the friction and drama of the Manet vs. Degas structure.

Yet in my two-painter household, the exhibition elicits spirited conversation. My husband, Mark, is avidly anti-Renoir. Amused by the trolling ‘Renoir Sucks at Painting’ protests over the years, he shares with many a visceral reaction to the paintings. This is especially true at The Barnes Collection where his distaste often flavors his experience. I don’t share the unilateral loathing but I was never too quick to defend Renoir–until this exhibition.

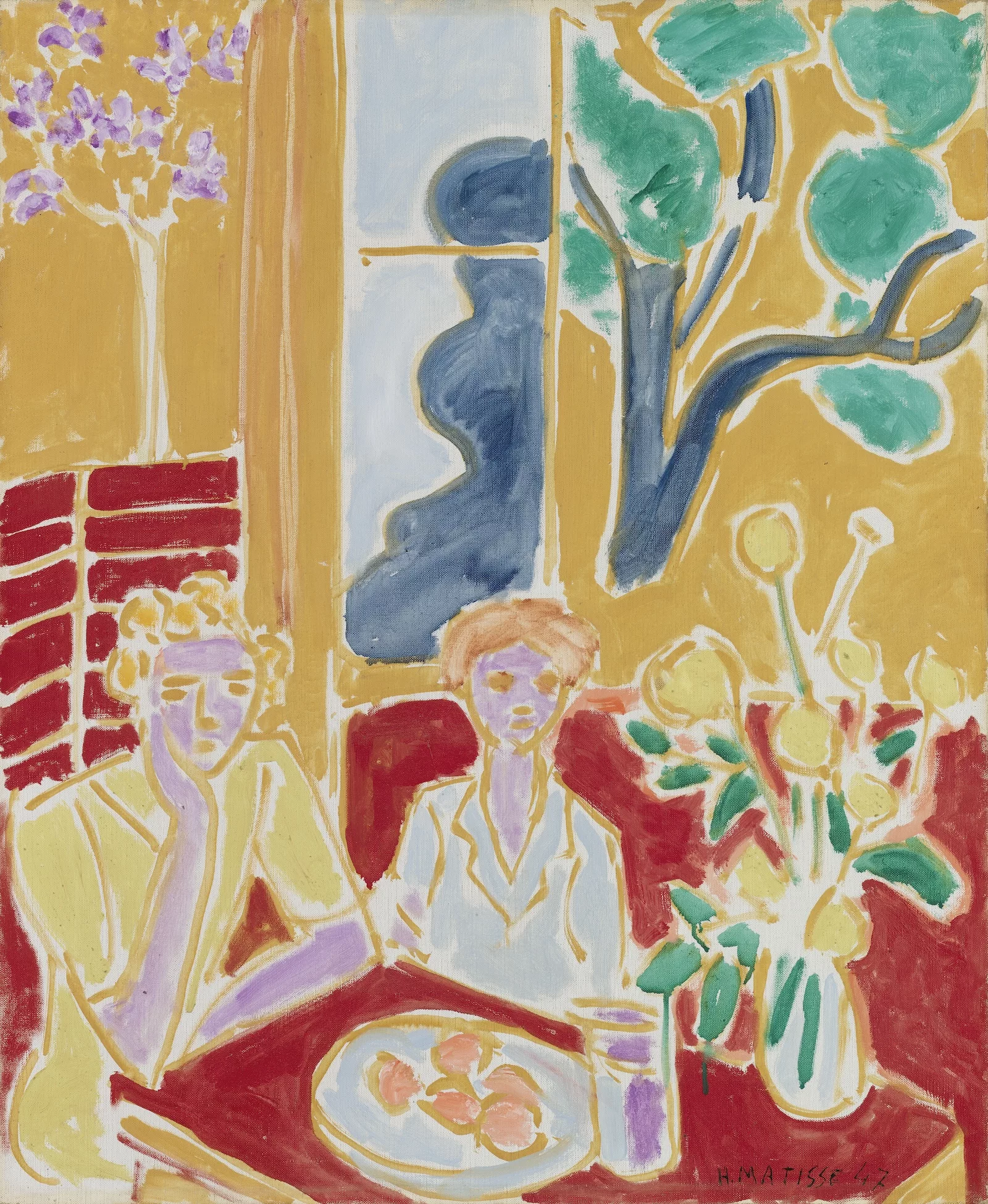

Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes provides the space and the distance to view the work from a better vantage. Installed in the Roberts Gallery, the exhibition builds slowly; reintroducing the artists first individually and then in tandem. Outside of the stacked and often crowded Barnes configurations (the “ensembles”), the artwork has room to breathe. I was surprised to find work that I had previously overlooked or paintings that appeared much larger than I recalled. I was not alone: I overheard one of the exhibition’s curators, Cindy Kang, admire the uncanny ability of one Matisse canvas to transform. “The more space you give it,” she observed, “the more it grows.”

Paced to invite quiet reflection, the exhibition presents two artists at different points of their career connecting through influence and admiration. Matisse – who was almost thirty years younger than Renoir – befriended the ailing and housebound artist during the final two years of his life. By the time the two met in 1917, Renoir’s rheumatoid arthritis was physically disabling and extremely painful. When Matisse asked, “Auguste, why do you continue to paint when you are in such agony?” His often quoted reply was, “The pain passes but the beauty remains.”

There are overlapping conceptual artistic themes – Renoir’s hazy nudes directly influencing Matisse’s later odalisques – that speak to a broader connection of color as content. Although Renoir may not have immediately grasped where Matisse was heading, he recognized implicitly the truth in his direction, validating the younger artist while modeling a life-long path of continued material exploration through disability. Whether or not you appreciate every work along Renoir’s own trajectory, the exhibition makes a strong case for the space he carved out for those that followed. His ‘bad’ painting – the wispy contours, sappy subjects, garish palette – opened windows for Matisse, Picasso, and Bonnard. Throughout his lifetime, Renoir built a strong community of avant-garde artists, and these exchanges enriched his practice and life.

Curators, Cindy Kang and Corrine Chong invite more contemporary connections with the Barnes Focus digital guide, where museum staff share personal reflections, a range of short asides that offer alternative routes to appreciation. These layers reinforce the relevance of painting — to speak outside of its limited timeframe and skewed demographic — by inviting fresh voices into the conversation. [The Barnes Focus guide is only available on-site in the galleries.]

For me, the museum staff’s shared stories reframe my on-going marital debate. I’ve dismissed my husband’s view of Renoir as a comedic exaggeration, deeply suspect in terms of connoisseurship and generalized cultural snobbery, but I now realize his distaste is not generalized. Mark reacts to Renoir the way that some people react to cilantro – it’s a gut reaction, and likely a matter of context and proportion.

Although we wouldn’t meet until years later, Mark and I both lived in Washington, D.C. in the late 1990s. He was working at The National Gallery in the gift shop, while I was working as a Museum Assistant (aka Guard) at The Phillips Collection. While Mark was bagging up reproductions of Renoir’s sugary ‘Girl with a Watering Can,’ I was often stationed in the room with “Luncheon of the Boating Party.” So while I spent time in a quiet room with a breezy painting, gently reminding guests to keep their distance; he was busy stocking the shelves with endless facsimiles: Renoir on postcards, prints, mugs and bookmarks. These are markedly different introductions to the same artist. My experience at the Phillips Collection was also moderated by curatorial restraint. Duncan Phillips, a contemporary of Dr Albert Barnes, owned only the one Renoir; in comparison with the 181 in the Barnes collection. When teased by his rival collector about the deficit, Phillips replied “It is the only one I need.”

Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes is an ideal context to revisit both artists’ work, in part because it turns down the volume on Barnes as a collector, rebalancing the mix. Ending with an expansive room of Matisse window paintings, this refreshing summer show is an opportunity to enjoy the world class collection right here in Philadelphia.

In the digital guide. Nicole B, who works in the museum shop, reflects on a Matisse interior, “This painting is a reminder to soak in the quiet moments wherever you might find them.” This anti-blockbuster, staycation show offers just that moment.

Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, until Sept. 8, 2024, Barnes Foundation

Read more articles on Artblog by Cindy Stockton Moore.

Cindy Stockton Moore is a Philadelphia based artist who works with aqueous media to create multimedia animations, works on paper, and site-specific installations. Her writing on art has appeared in FlashArt, ArtNews, NYArts Magazine, SciArt Magazine, The New York Sun, Past Present Projects and Title Magazine in addition to university and web publications. Cindy has been married to artist Mark Stockton since 2006; they agree on Matisse.