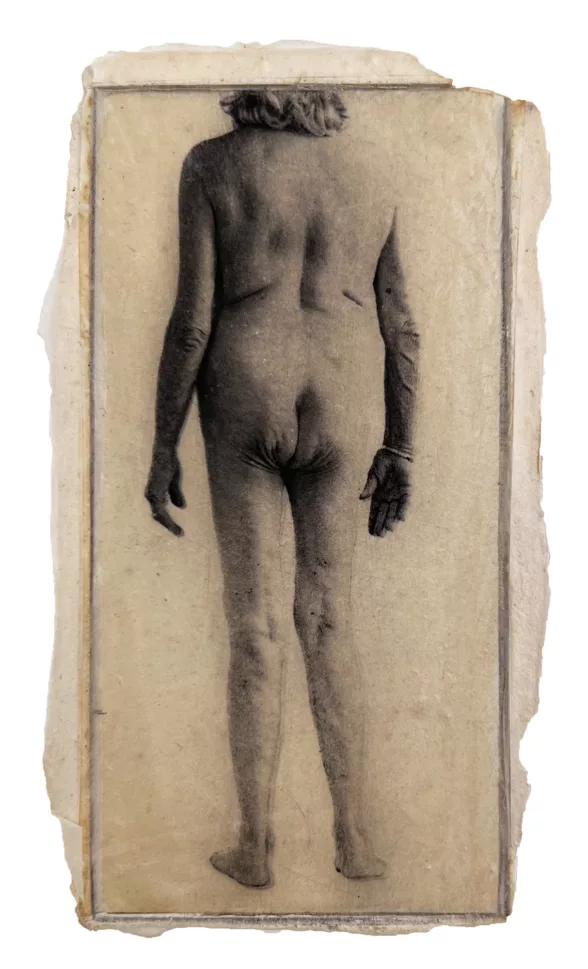

The exhibition at the Print Center is the first chance to see Nancy Hellebrand’s recent series, EVERYBODYBEAUTIFUL, in an art venue. The artist has had a long and distinguished career internationally, with work in many museum collections. Work from EVERYBODYBEAUTIFUL was previously accepted for exhibition and then rejected or censored three times. The bodies Hellebrand explores in this series comprise one of our remaining taboos: those of older women, depicted straightforwardly, and nude from the neck down. The exhibition is beautiful and surprising, revealing and provocative, and likely to resonate in memory long after viewing it.

Americans are used to seeing beautiful bodies and implied nudity to sell a vast range of products and services. But Hellebrand isn’t selling anything. Instead, she is offering attention, acceptance, and indeed, love, to the one thing we all share: our bodies. The artist has explained, “Faces are not included in the photographs because I want to see what each woman’s body reveals. Faces divert our attention from all else because we’re genetically programmed to look at them, so I don’t photograph above the neck. “

Hellebrand,79, loves the bodies of her subjects, who are largely her contemporaries. They are varied in shape, size and complexion and the women are comfortable in their own flesh, which is marked by time and experiences. They are survivors. The photographs reveal evidence of pregnancies, indulgences, surgeries, and the universal responses of flesh to sunlight, gravity and time. These women have had physical pleasures and pains. They are somebody’s grandmother, wife, lover, friend, colleague or neighbor. Our inclination to turn away from the sight of their flesh reflects our very narrow conception of beauty, highly determined by commercial imagery, and suggests a likely dissatisfaction with our own bodies, as well as our society’s denial of aging, and death – experiences we all share.

Much of Hellebrand’s photography has been motivated by a desire to know other people. Such work has depended upon the comfort she offered to strangers and the trust they returned, whether she was photographing Londoners at home, residents of Philadelphia in their neighborhood streets, or older women unused to hearing that their bodies were attractive and worth revealing. She has printed work in a broad range of formats and has produced EVERYBODYBEAUTIFUL in several variants, including color prints as large as 8 by 5 feet. But the scale and intimacy of the two series at the Print Center are essential to their impact.

Both are printed in photogravure – a late 19th century process associated with publications of the Photo-Secessionists, whose blurry forms reflected the romanticism of much Symbolist art as well as a bid to consider photography a fine art rather than a mechanical process. Photogravure produces a beautiful tonal range; this creates an initial dissonance with this series, which has radically different subject matter than early photogravures. Hellebrand’s digital files were converted and professionally transferred to copper and printed by Cindi Ettinger; one series consists of small images with very wide margins on 16 by 20 inch paper, the other printed on plaques of not-yet-dried plaster, 2 and a half to 6 inches in their larger dimension. Both invite viewers to study them at very close range. The Gampi paper she uses is translucent, mottled in texture and slightly wrinkled at the plate edges; in this context it inevitably evokes skin, which becomes fragile with age. The plaster plaques are at most twice the size of early daguerreotype portraits, which were clearly clasped in their owners’ hands, in love and remembrance. These plaques beg to be held, and Hellebrand suggests that we give these images similar respect.

Hellebrand’s subjects take ordinary stances rather than calculated poses. They do not reflect well-rehearsed imagery, or bodies presented for public view with stomachs sucked in and shoulders back. Some of the photographs reveal details of self-fashioning such as a necklace or bracelet, tattoo, a mask worn during the Covid pandemic, or painted toe nails. They also reveal spots of aging skin, prominent veins on hands and arms, stretch marks, sagging and lumpy flesh, all usually covered by clothing.

While nudes are a venerable subject in Western art, they overwhelmingly represent ideals of youthful beauty and prowess, other than the small figures of the damned in medieval Last Judgements, and a few seventeenth-century paintings of hermit saints, always male, whose sagging flesh records their lengthy penitence. The only older, female bodies to be seen are those of witches. There are few modern precedents, if one discounts photographs of ethnographic subjects and medical records of the disabled and insane, which were not created as art but have been cited by recent artists, as criticism of their values.

The only examples of nude older bodies that come to mind are self-portraits. Alice Neel, Joan Semmel, Lucian Freud and John Coplans revealed their own aging bodies without apology, and in Coplans’ case, with some humor at the lack of bravado his sagging flesh betrayed. The in-your-face photographs in which Jo Spence and Hannah Wilke revealed their bodies (and Wilke, that of her mother), disfigured by cancer and facing mortality, are hard viewing and clearly meant to discomfit the viewer. Wilke, however, demonstrated an acceptance of the way of all flesh that intersects, in part, with Hellebrands’s work. I was not surprised to hear that Hellebrand considers Coplans a mentor, although she did not study with him. In her photographs of other women aging she reveals her own vulnerability as a woman facing the social invisibility of the old.

This exhibition deserves a wide audience, and I hope it will travel. As our population is aging we only hear about physical problems and unmet needs of the elderly. We need the acceptance that these photographs offer and museums need work which promotes respect for diversity in its many forms. Hellebrand ‘s photographs would be suitable for any university museum, where medical students could see that the bodies of their patients are more than sites of symptoms, undergraduates could see beyond their anxieties about their own, late-adolescent bodies in the celebration of bodies they have never seen or have ignored, and visitors to all museums could have a chance to broaden their ideas of beauty, art, aging and the cultural values they reflect.

‘EVERYBODYBEAUTIFUL’ is on view at The Print Center through July 20, 2024.

Read more articles by Andrea Kirsh on Artblog.