Lines of flight: Experimental Dance in Philadelphia, 1968-2000; the first chapter of a biased history

By Megan Bridge

Dear Philly Artblog Reader,

Allow me to introduce myself. I’m Megan Bridge, and I have been living and working in Philadelphia as a professional dance artist since 2000. I adjunct in the dance department at Temple University (since 2016), and co-direct Fidget in Kensington. I was a founding writer with thINKingDANCE.net in 2011, and served as its executive director from 2014-2016. I perform, teach, and choreograph regularly in Philly and abroad.

When I pitched this article, it was in the context of a conversation with Roberta Fallon about how I’d like to contribute to the Artblog covering more dance and performance. Roberta and I agreed that a good place to start would be with a lay of the land, and some history and lineage about the Philly dance scene that I’ll be covering. I’ll also introduce some concepts and structures (often in endnotes) that I hope will be helpful to readers who are less conversant with dance as an art form. I’ll be writing more about independent or experimental dance in Philadelphia than concert dance.

When I started thinking about the landscape of experimental dance here, I developed a theory about what makes Philly dance special, and where I might be able to locate the origin of those characteristics. My theory is based on my own experience, therefore biased, and I knew I needed interlocutors for this project. As I started talking to people I realized that doing this project any justice would take a book, and the list of people I’d like to interview has grown to more than 30. But I have to start somewhere, so…here is the first chapter.* I started out by interviewing David Brick, Terry Fox, Ishmael Houston-Jones, and Zornitsa Stoyanova, with additional contributions from Lois Welk and Rennie Harris.

Group Motion – foundational to Philly’s experimental DIY ethos

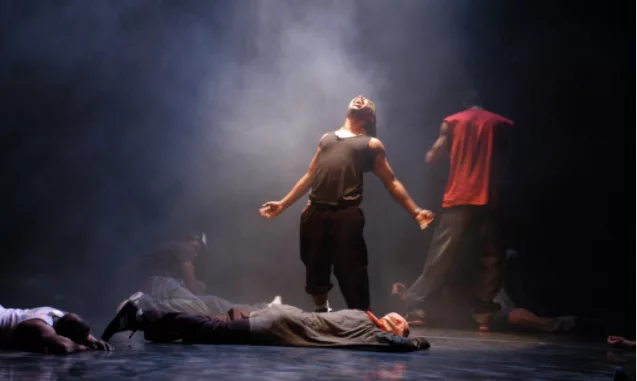

Philadelphia has become known as a hospitable incubator for experimental dance and new hybrid performance forms. The city’s burgeoning performance scene has led to and been supported by the development of schools, organizations, and collectives where experimental performance has flourished, like FringeArts, Mascher Space Cooperative, Headlong Performance Institute, Cannonball, and Icebox Project Space. There’s something particular about Philly experimental dance that distinguishes it from work coming out of other cities.

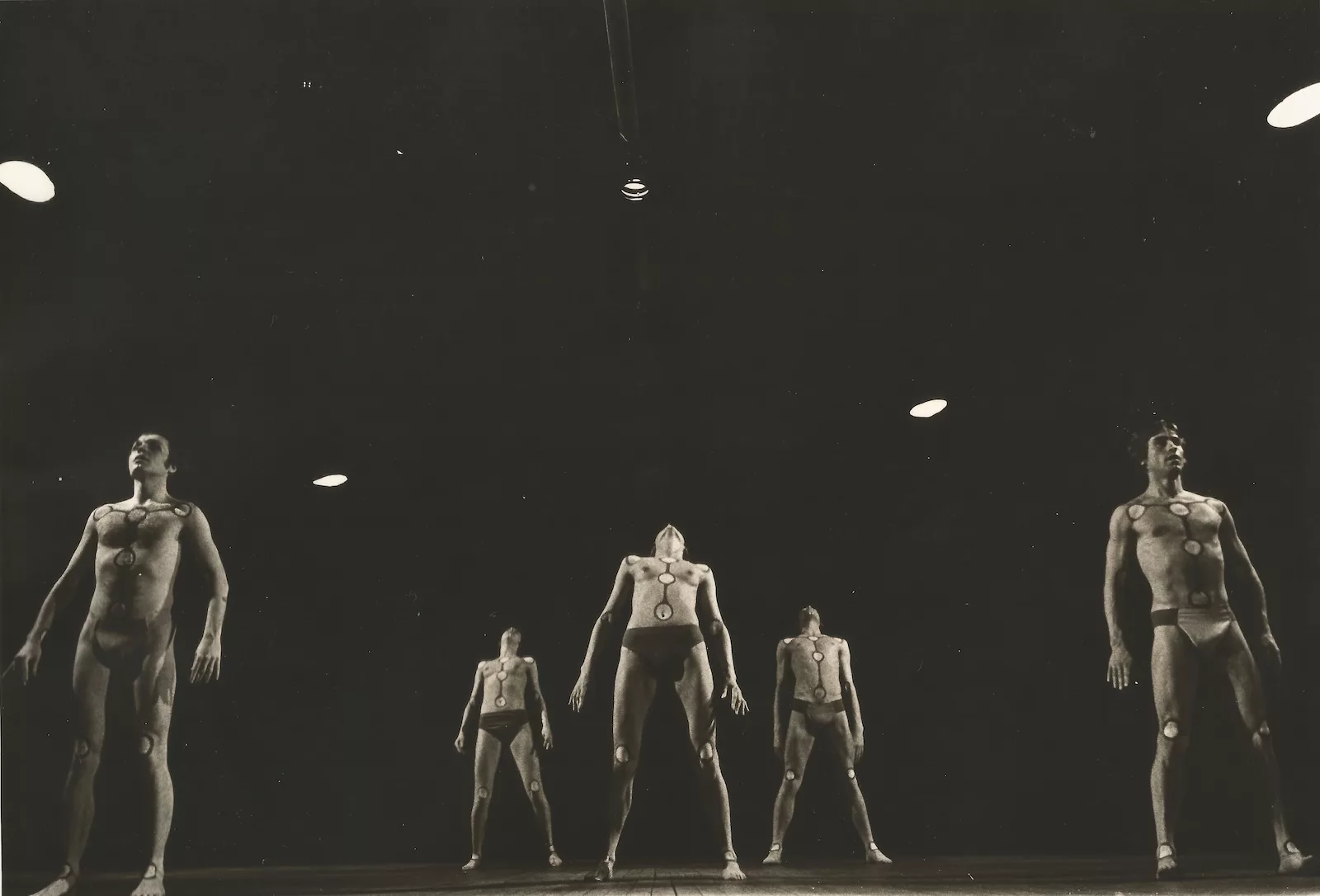

Foundational to Philly’s experimental dance narrative is the arrival of Group Motion Multi-Media Dance Theater from Berlin in 1968. Led by Brigitta Herrmann, Hellmut Gottschild, and Manfred Fischbeck, Group Motion’s arrival marked a pivotal moment in the city’s artistic landscape. Group Motion’s collaborative nature, emphasis on improvisation, and aesthetic commitment to presence and emotional expression has visibly impacted performance in Philadelphia, giving rise to a lineage that is easier to trace out in a rhizomatic pattern than in a line.

Herrmann and Gottschild were students of Mary Wigman, the German Expressionist choreographer who shaped modern dance in Europe and was contemporaneous with Martha Graham in the US. Wigman’s technique was largely improvisational and did not center on a particular set of movements to be learned, rather focusing on the practitioner’s embodied experience to generate movement from within.

Like other art forms in the German Expressionist tradition, Wigman’s dance work tended towards the dark, raw, emotional, and often sprang from existential themes. Group Motion brought these values along when migrating here in 1968, establishing a contrast in Philadelphia to much of the experimental dance work coming out of New York at the time, which was characterized by a stripped-down, post-modern aesthetic and more flat or neutral approaches to emotion, typified by Yvonne Rainer’s iconic Trio A.

1940s – LaVaughn Robinson and African diasporic dance and music

In the decades prior to Group Motion’s arrival, the existing performance scene in Philadelphia had been shaped by African diasporic forms of dance and music. Tap dance legend LaVaughn Robinson commanded the most sought-after busking corner at Broad and South Streets by the time he was 13 years old in 1940; he went on to perform in nightclubs and concert stages around the world, eventually joining the faculty of University of the Arts in 1980 and being recognized by the NEA as a “Living National Treasure” in 1989. (At the time of Group Motion’s arrival in ‘68, Robinson was living in Boston.) Philly was also known for its jazz music scene in the mid-twentieth century, home to improvisations and jam sessions that characterize the form. By the end of the 60s, this “golden age of jazz in Philadelphia” was coming to a close, due to changes in both public taste and in the music business.

1960s – Temple University, Dance Modernism in Philadelphia

In 1965 in Philadelphia, Temple University’s dance department had not been formalized, but there were dance electives available as PE courses. Around that time, Instructor Kathy Pira taught modern dance there in a range of different styles; she encountered Group Motion in Berlin while on a sabbatical year and was partially responsible for their emigration here. (Founded in 1975, today Temple’s dance program offers a PhD, one of only four programs in the US to do so.)

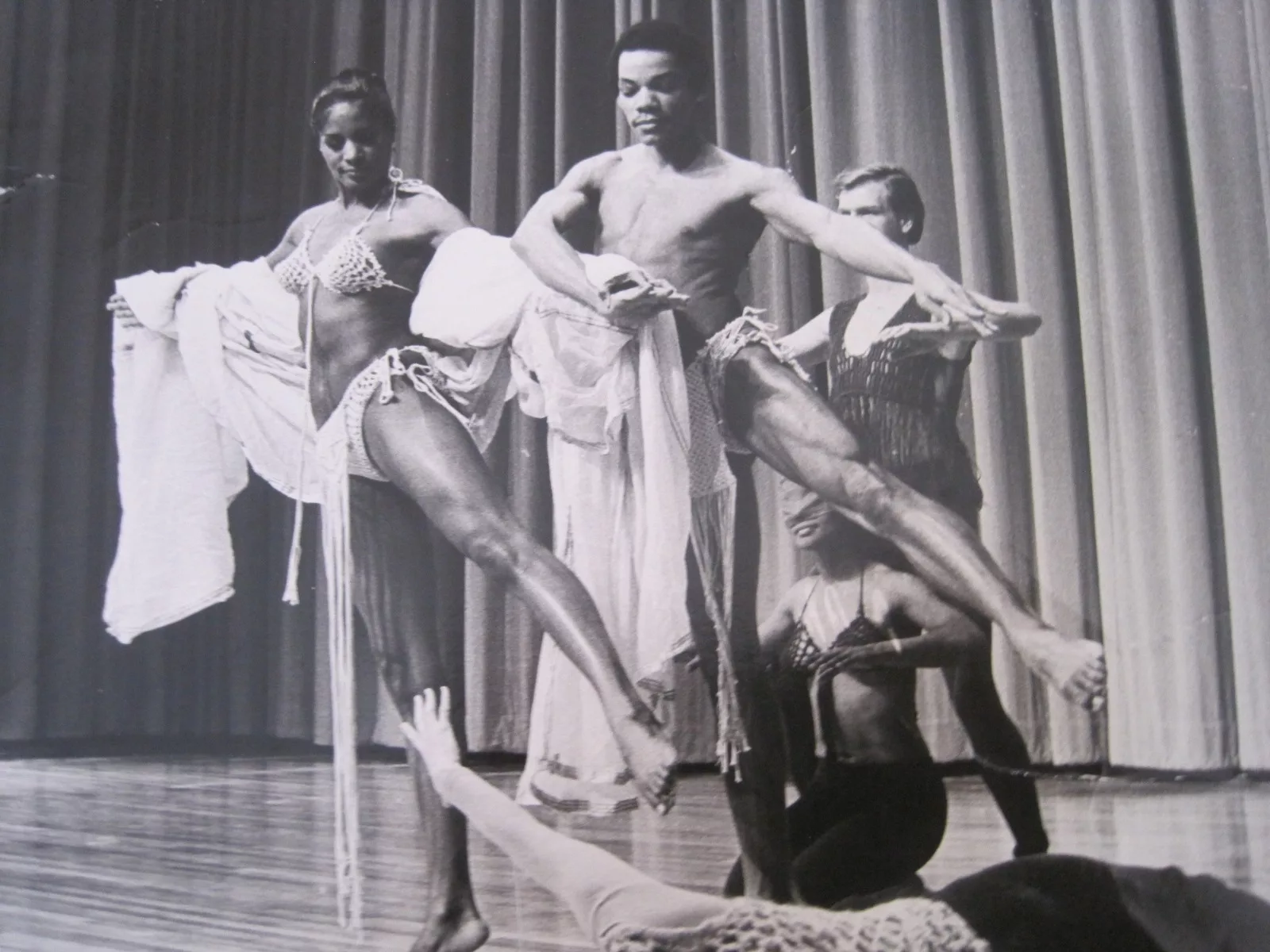

On the other side of town, Joan Kerr was establishing her Lester Horton-based company, “one of, if not the first, racially integrated dance companies here,” according to the Philadelphia Local Dance History Project, created by Philadelphia Dance Projects whose director, Terry Fox, has been a dance artist and producer in Philadelphia since the 1960s.

Horton technique comes out of dance’s high modernist period (think Martha Graham). Modern dance is often imitative–the dancers imitate the choreographer, or the students imitate the teacher, in the form of a particular movement technique or style–as opposed to generating their own body movement through improvisation or other experimental means. Modern dance is often shape-oriented, calling for specific positions of the body and a set of repeatable movements in the classroom as well as on stage. But at Joan Kerr’s Horton technique class in Philly in the late 60s, as Terry Fox remembers, “every dance technique class ended in free improvisation.”

Modern dance and concert dance** were getting established in Philadelphia by the early/mid-1960s by Joan Kerr and the like. The Philadelphia Ballet (formerly known as Pennsylvania Ballet) was established in 1963. Joan Myers Brown established her school of dance arts in 1960 to provide performance opportunities for Black dancers, and in 1970 she founded Philadanco, a modern dance repertory*** company. Later on, Faye Snow, a student and company dancer with Joan Kerr, established Juba Contemporary Dance Theatre, whose work was often inspired by pop music and Black culture, and at the same time carried on Horton choreodrama traditions.

1968: Group Motion’s experimentation, collaboration, and communal living.

In 1968, Group Motion arrived on fertile ground: improvisation was deeply embedded in the Black culture of Philadelphia in street dance as well as jazz, and concert dance was getting established; much of this work valued depth of emotion. Post-modern approaches to making, which included collectivity and multidisciplinarity, were well underway in New York. The company established its first studio at 5th and South Streets. Influenced by the communal living movements of the 1960s, many Group Motion company members lived together, often dancing for long sessions under the influence of psychedelics. Their workshops and performance events drew all kinds of people who were welcome to join in, participating through collective movement improvisation or sometimes being asked to join the collaborative mix as a musician or visual artist.

Group Motion’s experimental, collaborative structure was housed in a decidedly German Expressionist aesthetic, with larger than life ideas coming through.

Terry Fox, who encountered improvisation at the end of Joan Kerr’s Horton classes in the mid-60s, went on to dance with Group Motion in the early 70s. She said:

When Group Motion showed up, they were sort of the only interesting thing on the scene, so everybody went and took classes with them. They asked me to join the company. Those original dancers were mostly from Joan Kerr’s group, everybody was in everybody else’s company. Manfred and Gitta had been teaching at Uarts, and they recruited all these non-dancers, a bunch of visual arts students, that were fun to be around. They wanted everybody to live together, you know, to share the same space. And they did, most of them lived on South Street… It was easy for an art student to jump in, get energetic, get skills. It wasn’t demanding in the way that Horton technique or Graham technique would be. It was freer. And then they could improvise with what they had learned or their own kind of personal idiosyncrasies and gestures.

In the structure of the pieces there was always some meaning about, you know, this great cosmic thing was gonna happen. They were almost a little apocalyptic, you know, like we’ll all be together and be going off into space and stuff like that.

Multidisciplinarity is a key, almost taken-for-granted feature of Philadelphia’s experimental dance, in a way that can sometimes make Philly’s aesthetic simultaneously DIY and larger-than-life. Group Motion was a “Multi-Media Dance Theater” from the start, and in our city there have often been collectives and collaborations that include artists from many disciplines.**** In Philadelphia performance-making, it often feels like it’s more about who is in the room, and whether you want to be there together, rather than the discipline or even content of the work. Headlong Dance Theater’s David Brick calls Philly experimental dance “inherently transdisciplinary in a comfortable, almost casual way.” Other places where transdisciplinarity has been woven deep into aesthetics are the Gesamtkunstwerk, in the Bauhaus, and in Mary Wigman’s work–all Germanic legacies that accompanied Group Motion upon their arrival in Philadelphia in 1968.

Group Motion Leadership and splits

Although collective values were pursued and espoused, the leadership structure within Group Motion was clear, with Fischbeck, Gottschild, and Herrmann at the helm. Due to personal and aesthetic differences, Gottschild left Group Motion in 1972 to form his own Zero Moving Dance Company (later ZeroMoving), and some of the dancers followed him. ZeroMoving performed throughout Philly and toured to Europe, relying on “stunning scenography and dancing, largely by Hellmut and Karen Bamonte,” according to dancer and choreographer Ishmael Houston-Jones, who arrived in Philadelphia that year. Gottschild taught at Temple University from 1968-1996, and many professional dancers in the city took his class regularly, as well Eva Gholson’s class. Gholson is a modern dancer and the first black woman to dance at the Merce Cunningham Studio in NY in the 1960s. It was easy for local professionals to join university students in the studio at Temple, as there was little gatekeeping in the newly developing dance department.

Over on South Street, the Group Motion Friday Night Workshop was getting started in the late 60s. The workshops, which continue today,***** start with a breathing meditation and progress through a series of movement and game playing structures. According to Houston-Jones, the workshop was a nurturing, immersive environment. Anyone could show up and move within the landscape of live music, film projections, and a psychedelic vibe. It was focused, though, not a free-for all, “Brigitta was on the microphone giving guidance to this very rich, multidisciplinary experience.” Houston-Jones danced with the Group Motion company for two years in the early 70s, appearing in two concerts.

Lack of city support and development drive artists out of Old City

Around the same time, Terry Fox (and soon others, including Houston-Jones) left the Group Motion company and went to Old City to form a splinter group at a shared loft with other dancers and musicians where everyone had a key, and would show up to jam together. “We just wanted to do things more untrammeled, more open. You know, actually freer,” she explained. But then, like now, resources were limited for dance in Philadelphia. Fox said:

The city never came in behind anything. But the city did put together a feasibility study to develop Old City. In other words, get the artists out and make lofts. So after 5 years there was a big exit, people moved to Northern Liberties, Jac[alyn] Carley went to Berlin to found Tanzfabrik, other friends went to San Francisco, Ishmael [Houston-Jones] went to New York, and by ‘83 I was in New York, too. It was pretty much destroyed by development.

1980s – Group Motion’s Dual structure – performing company and community workshops

Meanwhile, throughout the 1980s, Group Motion settled into its dual structure: a performing and touring company of professional dancers and the ongoing Friday Night Workshop open to the community. In 1989, Brigitta Herrmann formed her own company, Ausdruckstanz Dance Theater, which was even more intentionally tied to the Mary Wigman principles. In the late 90s, Herrmann pursued a graduate degree in dance therapy at Naropa University, while the company continued under the sole leadership of Manfred Fischbeck for a time. When Herrmann returned to Philadelphia, her research into somatics and holistic health contributed to framing the Group Motion Workshop as a healing modality. The organization continued under both directors until Fischbeck’s passing in 2021. Herrmann continues on as Group Motion’s sole artistic director today, performing her own solo work, leading the Group Motion Workshop, and training a new generation of facilitators to carry the work forward. She is 86 years old.

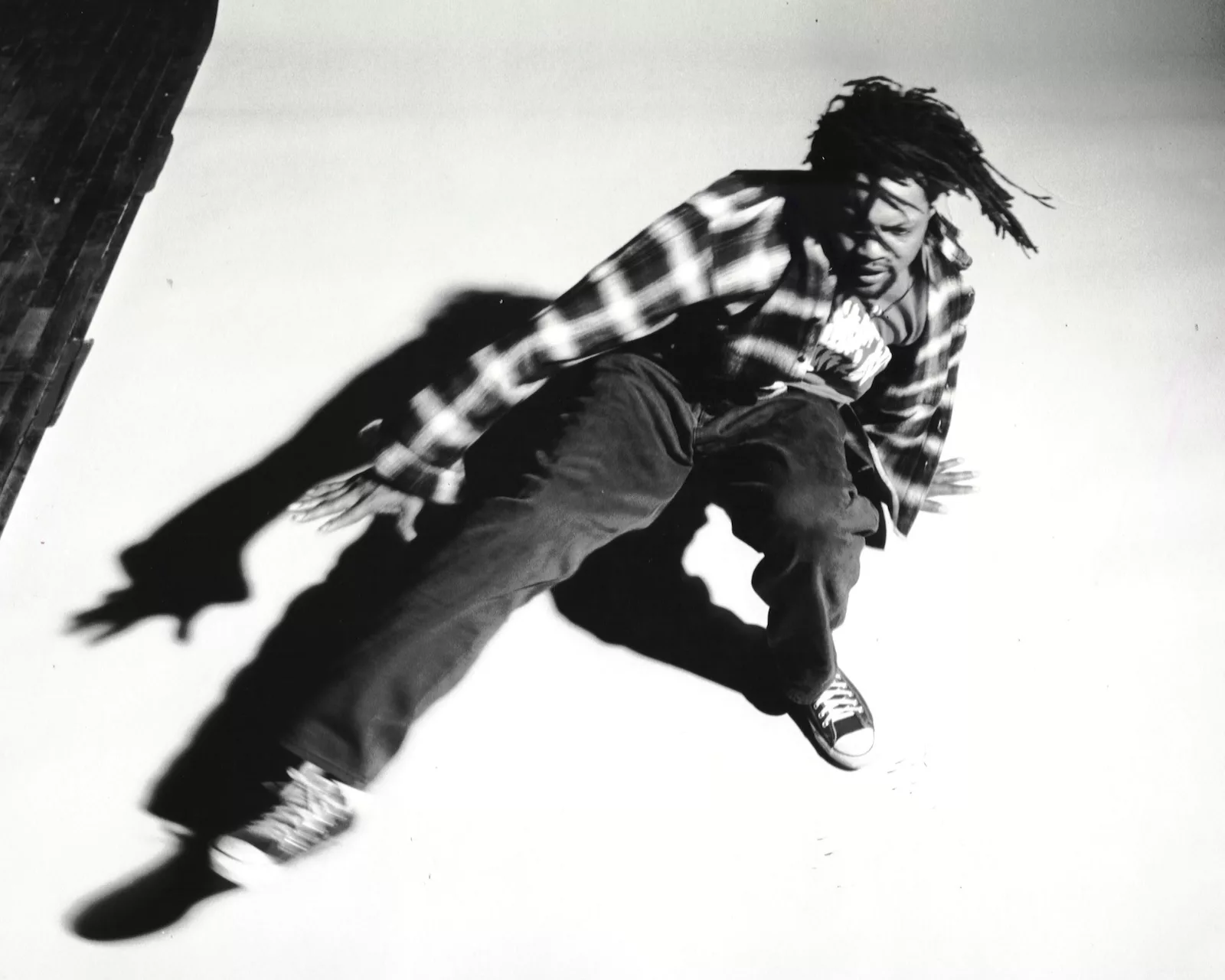

1990s – Rennie Harris and street dance: affect that is Africanist and experimental

Street dance choreographer Rennie Harris, who has been voted “one of the most influential people in the last one hundred years of Philadelphia history,” grew up in North Philadelphia. Harris was first inspired to dance by watching Don Campbell and the Campbell Lock Dancers on TV. In his teenage years he performed in local bars and lounges, and then became co-captain of the popping crew Scanner Boys and later toured as a member of the Magnificent Force, opening for artists like Run DMC, Afrika Bambatta, Sugar Hill Gang, Madonna, and more.

After his stint in the commercial scene, Harris returned to Philadelphia in the early 90s and joined the short-lived dance and music ensemble The Splinter Group, whose goals were to “distill, juxtapose and celebrate cultural differences.” Here, Harris encountered other artists experimenting within their own forms, like Roko Kawai who was influenced by Japanese classical dance, American Modern dance, Jazz dance and Hip Hop.******

Rennie Harris Puremovement******* was founded in 1992. Up until this point, Hip Hop dance had been seen in theaters, on stage and on TV but it was mostly for entertainment. Harris was staging street dance in a more experimental art context, expressively, abstractly or with a narrative. Harris’s work juxtaposes high affect emotion with an underlying cool aloofness that is inherited from the Africanist presence in Philly********. The often intense facial expressions and body postures, conveying angst and struggle in his work are tempered by subtle work with affect and presence. These qualities can also be seen in Group Motion’s dances over the decades, and point to another commonality in Philadelphia dance.

Unique emotional content of dance work in Philadelphia

There is a straightforwardness in the emotional content of Philadelphia dance work, some might call it earnest. Lois Welk is the Artistic Director and Co-founder of American Dance Asylum and spent eight years in Philadelphia as the director of a dance service organization funded by William Penn Foundation, Dance UP!, from 2007-2014. She says “Philadelphia dance is beguiling. There’s a lot of ‘This is me in this, and I’m not compromising, and here you go.’”

Indeed, a common thread woven through much of Philadelphia dance across many sub-genres in the field is a deep commitment to emotion, and a highly examined sense of performance presence in the work.********* Philadelphia dance artists are crafting states of being in their choreographies, in very particular ways. The artists of Headlong Dance Theater like to discuss the “psychic choreography” in a work–what are the performers experiencing internally, what are their states of consciousness?

1993 – Headlong Dance Theater and Philly’s collaborative, multivocal approach to dance

Exactly 25 years after Group Motion’s arrival in Philly, Headlong was founded here in 1993, again by three different choreographer-directors: David Brick, Andrew Simonet, and Amy Smith. This was another important phase shift in the cultural dynamics of Philadelphia’s evolving dance community. Headlong shared many values with Group Motion, such as a multi-vocal approach to making, a commitment to play and audience interaction, and placing improvisation at the center of its work. When Headlong arrived, its three directors also shared living space, and later began a free First Friday series at their studio in Old City where they tested out new work every month.

As Headlong grew, it too had a broad cultural impact on Philadelphia’s dance and performance scene. This included the way the company supported its dancers to make work in their own right, a value that was also emergent in Group Motion’s company structure and presenting platform over the years. In both companies, the dancers contributed collaboratively to choreography. Group Motion company members were invited, alongside other professional artists in Philly or guests from elsewhere, to try out new work in Group Motion’s presenting series, “Spiel Uhr.” The company sometimes even invited dancers to bring their own short works on tour. Headlong shared many of these values, giving rise to a new generation of choreographers who formed their own collective dance company called Moxie, which later became Nichole Canuso Dance Company. Later still, Headlong created a school (Headlong Performance Institute) and an incubated artist platform that offers fiscal sponsorship, space, and organizational support to independent artists in Philly.

The collaborative, multivocal approach is a recurring theme across decades of experimental dance here.

According to choreographer David Brick, work from Philly is:

deeply collaborative, as opposed to this strident singular author’s voice. Being able to recognize a work that allows multiple voices to interact with the other, to contradict each other in a single work of art, that multiplicity is, I think, characteristic of Philadelphia.

The clarity of the singular voice of the author is often held up as a standard in the international art world, where star culture and capitalism turn artists’ names into brands, even in the small, esoteric market of the experimental dance scene. Philly has resisted this across generations, a trend that can be witnessed in names of local dance companies, which often do not bear the name of one artist. (Example: Group Motion Multi-Media Dance Theater as opposed to Martha Graham Dance Company). Dance artists here have favored multivalence over refinement; complexity over legibility in a work.

The politics of the work – collaborative making

In her essay “The Politics of Method,” author Stephanie Skura explains that how the work gets made are its politics. Multivocal, multivalent, multidisciplinary. These observable traits say something about the politics of making work in Philadelphia. How is it happening? According to choreographer Zornitsa Stoyanova, a Bulgarian dancer who came to Philadelphia via Bennington in 2006, established her company BodyMeld and lived in Philly for 10 years, and is now an international artist:

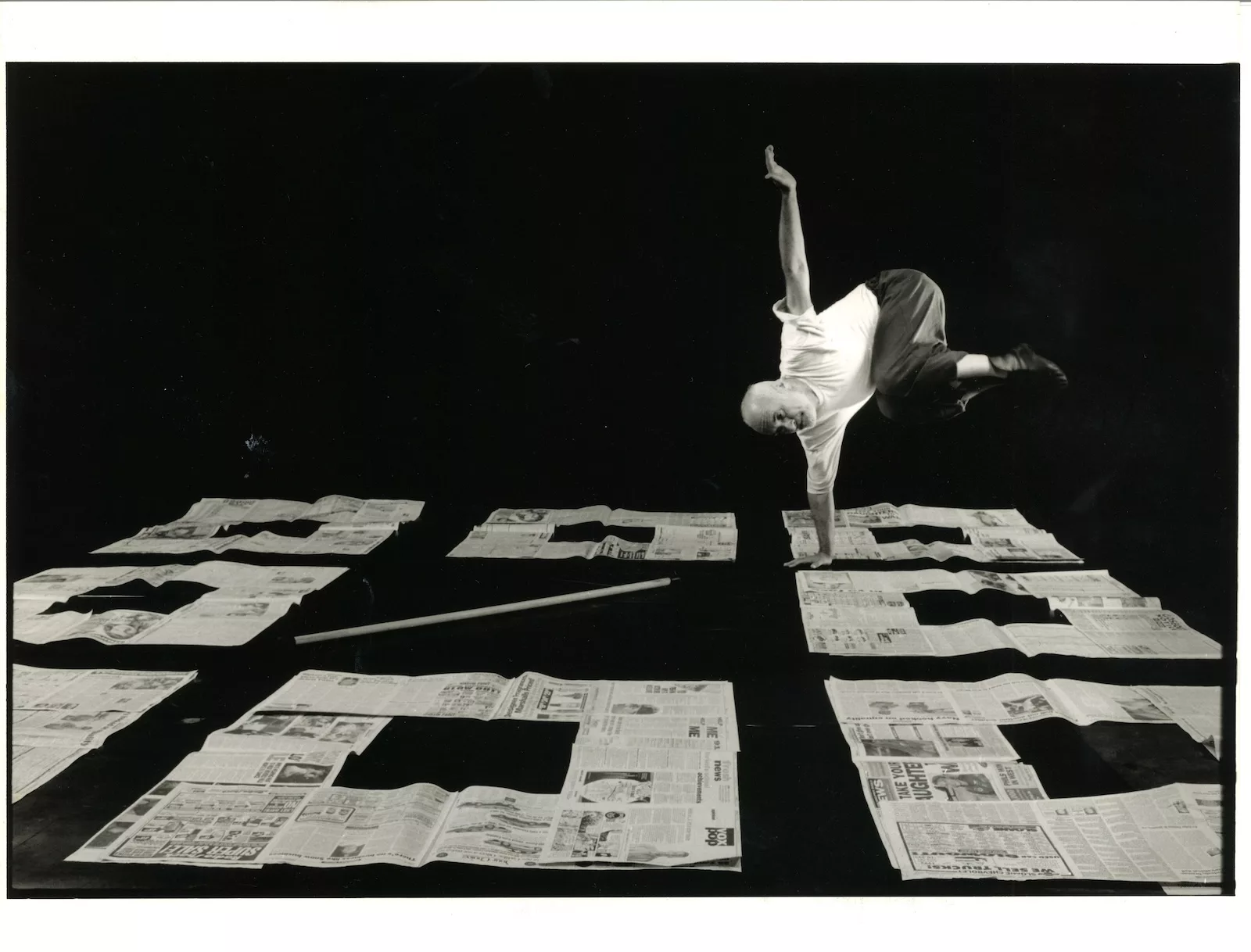

People that come to Philly don’t work in terms of, “I have a theme. I wanna make a piece about inequality, so I’m going to read the news, and then I’m gonna read all the papers that are coming out, and then devise an exercise for other people to do that speaks of my research.” It’s just not that kind of working. It’s a devising method, finding tools, actions, states. You set up actions, you interrogate your actions, and then you get to something. People go to the source, they discover by doing instead of by thinking or writing. They use physical ways of exploring, maybe it’s through language, maybe it’s through different rituals or through music. But those explorations are then seen, visible. The body is not just gone in service of the idea. The body is together with the idea on stage. The experiments actually are the thing that ends up being in performance, not just a product of the process that gets thrown away.

In a chicken-or-egg scenario that has reproduced itself over several generations of artists, Philadelphia has dancers who are also makers. Of course there are exceptions, but in general, in the experimental dance community of Philly, most dancer/performers here are also making work in their own right. Says Headlong’s David Brick, “We relied on people being makers, not just dancers who are told what to do. We could not have made the work we made if there wasn’t already a scene in Philadelphia that was allowing people to develop those skills.”

Brick named Group Motion as key to creating that scene—indeed, for a while it was difficult to find a professional dancer in Philadelphia who hadn’t moved through Group Motion company or been adjacent to them in some way. And Group Motion propagated their values through not just the performing company and the workshop, but through multiple forms of community support as well. Formed in 1998, “Kumquat” was an artist-driven collaborative structure, spearheaded by Group Motion who invited three other companies to share office space, studio space, and other resources: Rennie Harris Puremovement, SCRAP Performance Group, and Ausdruckstanz (Ausdruckstanz was later replaced by The Bald Mermaids after Brigitta’s departure from Philadelphia). Kumquat was launched at Group Motion’s studio which by then had moved over a block, to 4th Street, just off South. In 2000, the cooperative migrated to West Philly and took up residence at the Community Education Center, where Group Motion maintained office space until 2024, and now holds a once-monthly Friday Night Workshop there.

Today’s scene – collective, connecting and the Philly vibe

Today, collective values like this are championed by many ensembles working in dance and theater here, for example the Mascher Space Cooperative, a space for new dance in Philly that started in Kensington in 2005 and now shares a studio with Headlong in South Philadelphia. Sharing resources and a general feeling of mutual aid is just how work gets done here. Again, according to Stoyanova:

Everybody’s hustling, busy with their own thing, and trying to promote. And yet there is an openness, a desire to connect, even if there’s no time, even if there’s no ability to go to each other’s shows, there is an incredible desire to engage in conversation and exchange. I’ve not experienced ego battles in Philly in the experimental dance scene. It’s not that it doesn’t exist. I think that we all internalize it because of capitalism and how we live and who gets the grants and all that. But our community in Philly is still super open and willing to help each other, regardless of the circumstance. If somebody is not actively able to help, then they know how to point you to get the needed help.

This kind of connection is what makes Philly a big city with a small town experience. We see each other in Philadelphia in a way that feels different from other cities, where there is the possibility of anonymity. According to Ishmael Houston-Jones:

Philly is very different from New York, vibe-wise. There’s sort of a rough edge, and people are really expressive on the street, in a way in which New Yorkers aren’t. There’s more of an avoidance in New Yorkers, you’re not making eye contact on the street, you just don’t do that in New York. It’s like–cheesesteaks. There is this sort of Philly vibe.

Can artists live on vibes? No, but they actually can build projects out of them. And ideally, with projects can come paychecks. Brick told me about making Headlong’s 2000 work “Ulysses: Sly Uses of a Book by James Joyce,” which feels like an apt metaphor for Philadelphia’s aesthetic of multiplicity and connection, and says something about the politics of how work gets made here.

The idea for “Ulysses” was planted during a weekly class Brick sat in on at the Rosenbach Museum on Rittenhouse Square. Over two course sessions on James Joyce’s Ulysses with Joyce scholar Vicki Mahaffey, Brick discovered that each chapter of the book represents a different style in the history of English literature. It’s “elliptical and deeply complex, but deeply coherent around a set of ideas…and that’s a fit for Philadelphia in a lot of ways,” he explains. It’s also a deep fit with choreography, at least the kind of choreography that Brick wants to see. The Rosenbach ended up commissioning the piece, and Brick “worked with Vicki casually, she was never hired, but there was this intellectual seriousness, the research unfolded over a couple of years. We had a mutual excitement about these Joycean ideas, which are all about multiplicity.”

Brick told me this story to elucidate a kind of serious rigor, and simultaneous openness to possibility, that characterizes dance and performance work in Philadelphia. He points to the content and the way that the ideas unfolded (spontaneous, serendipitous, multiplicitous) as well as to Headlong’s working conditions in the nineties. Headlong was started as a collaboration between three people living together and sharing all of their resources. Being free of economic barriers, according to Brick, “makes a piece like [Ulysses] possible. A piece like that just can’t happen without all those factors and those factors have a lot to do with Philadelphia in a number of ways.”

Over and over again, through generations, Philly’s dance work has embraced collective values, has shapeshifted and DIY’d itself into uncompromising existence. Perhaps that’s another overarching value in our dance community–sheer, wild, uncompromising existence. There is no shortage of ideas and people ready to try and make things happen. I’ll give the final word to Stoyanova:

Something about life as an artist in Philadelphia makes it sane. You can have an artistic inquiry, and an artistic life, even if you don’t ever make money off of it. I think maybe it has to do with the way in which we talk to each other, and how we prioritize the work. Because none of us will say, “Oh, I’m not going to do the work. It’s not time yet. I’m gonna wait for next year.” Nobody would say that, everybody would be like, “Oh, well, I have an idea, and I have a backyard. And I can buy beer. So let’s see what happens.”

END NOTES

* I am interested in inviting responses from readers, and I want to be transparent about the bias of this article. It is written from my own experience, and is not meant to be comprehensive in any way. If I’ve gotten anything wrong, or people disagree with my perspective, I would love to hear from them and create a multivocal dialogue, in true Philly style! Please send comments to: megan@thefidget.org

** It is useful to establish the difference between concert dance and experimental dance. Picture concert dance on a traditional stage with wings. The choreography and music tend to be fixed (as opposed to improvisational), and it is often performed by larger groups of dancers but choreographed by a single artist. It is also sometimes referred to as modern dance. Experimental dance, in contrast, is often performed in smaller black box theaters or outside the theater space altogether, in galleries, museums, outdoors, etc. Experimental dance is more likely to contain pedestrian or improvised movement, and the dances are often derived in collaboration, with dancers creating their own work together in small groups. This binary is in reality a continuum, of course, and often dance projects take on elements of both or are even scalable to work in multiple contexts of the dance world.

*** “Repertory” means that the company performs choreography by many different artists, commissioning new work, reconstructing historic work and returning to their own classics over the years, as opposed to performing the work of a singular artist. Most ballet companies are repertory companies, but this is less common in concert modern dance, where companies are more likely to perform work solely by a founding choreographer.

**** Another example from the 90s was Convergence Dancers and Musicians, led by choreographer Janaea Rose Lyn. As the company name suggests, Convergence was multidisciplinary, with many of the projects being driven by original music by local composers.

***** Full disclosure of bias: I am a certified Group Motion Workshop Facilitator. For more information on Group Motion workshops or my classes, go to https://www.groupmotion.org/friday-night-workshops or https://www.thefidget.org/movement-improv-class

****** Kawai went on to make her own work as well as dance with Leah Stein, a leading choreographer in Philadelphia who established her site-specific dance company in 2001.

******* Although Harris’s work moves through the context of concert dance, I include him in this narrative because he has had so much contact with the experimental dance world in ways that have created aesthetic reverberations in both directions. To disclose another bias, I am currently working on a project choreographed by Harris. Brenda Dixon Gottschild, mentioned in the note below, is an embedded scholar and writer on the project. For more information: https://www.thefidget.org/projects/rennie-harris

******** These ideas are from Brenda Dixon Gottschild, a groundbreaking dance theorist who has published four books, lives in Philadelphia, and married Hellmut Gottschild in 1989.

********* Headlong Dance Theater’s David Brick explains, “so much Philadelphia work cares about meaning and emotion. Of course, that makes it vulnerable to the critique that the post-moderns have: there can be overweening, preachy meaning and histrionic emotion. But the good and best work in Philadelphia never abandoned emotion.”

Megan Bridge is an internationally touring performer, choreographer, educator, and dance scholar based in Philadelphia. She is the co-director of Fidget, an organization for experimental performance. Bridge has presented her choreography at The Philadelphia Museum of Art, FringeArts, and many other venues in Philadelphia and throughout the United States in Detroit, New York, Pittsburgh, Phoenix, Washington DC, and more, and internationally throughout Germany and Poland as well as in Vienna, Sofia, Bogotá, Tbilisi, Skopje, Rennes, Johannesburg, and Zurich. She is currently working on a solo choreographed by Street Dance choreographer Rennie Harris, and she has worked on projects by Jerome Bel, Steve Paxton, Lisa Nelson, Lucinda Childs, David Gordon, Headlong Dance Theater, Group Motion, and many more. Bridge holds a BFA in dance from SUNY Purchase, and an MFA in dance from Temple University, where she currently serves as Adjunct Assistant Professor in the dance program. She previously served as Executive Director for thINKingDance (as well as writer and editor), and is a new writer on dance and performance for Artblog. She has published more than 30 articles for thINKingdance.net, as well several articles for the Dance Chronicle, Dance Magazine, and Pointe Magazine. Fidget