My Devil Mask

Did you know my older brothers tried to get me to climb into the laundry room dryer? Repeatedly.

I shouldn’t tell this story. It makes me seem vacuous, dull-witted and foolish, but at the time I was shamefully all these things.

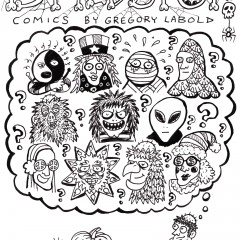

At five years old, the youngest and most beaten up of the three boys in our family, I sought a modicum of solace in a cardboard box. The Halloween costume featuring a cartoon devil and endorsed by Vincent Price himself.

Bernie, the chubby stationery store man who owned Colony Cards on Merrick Road, stocked this and other costumes on his candy store shelves. Colony Cards was a destination for all things candy, cards and toys. With my childhood friends, hours and hours were wasted there, studying model airplane kits, the wide offerings of chocolate bars, penny Bazooka gum, and 10-cent comic books. But the devil mask was my absolute obsession, and Halloween was the biggest day of my life. I desperately wanted the Devil Mask and talked about it all the time to the maddening annoyance of my parents. I even dreamed about it. Putting it on I suddenly possessed amazing superpowers. I could fly, fight and do division. I could change my life. I couldn’t wait for Halloween.

Neatly folded in a box with a clear plastic top, the devil mask looked like a cold cake with cherry red icing, the face sneering upwards, promising hellfire and revenge. It had my name on it! Since mid-August of that year (1964), I thought non-stop about that box… and the power and truth that would be mine once I unleashed it. I’d heard (and fully believed) I could really be someone else on Halloween night.

“I really really want that,” I told my mother and my father greedily. “I want the Devil costume for Halloween.”

“We’ll see,” my mother said. “Halloween is months away. Really!” It didn’t matter. I cried, I shrieked. I wouldn’t stop. Every day, every hour for months, I rattled on about the devil outfit. Would my mother deny me this life altering chance to dress up and become the devil and assume these magnificent powers?

“We’ll see,” she said.

Fascinated by the bright, brutal colors, the devil was my great seduction. I knew little, however, who the devil actually was or why he was so famous, but it mattered little. I was never as hungry for anything as this. I was mad for it. The devil mask would insure my invincibility, like firecrackers exploding harmlessly in my fingers (I’m invulnerable!) and having clever things to say all the time, and oh, laughing out loud, something I rarely did. I would be able to defend myself against my two older brothers whose sole occupation was to torture me morning, noon and night.

For days on end, I wailed and whined for this thing. Then, finally, finally! Just three days before Halloween, my mother relented and dropped the $1.95 on Bernie’s counter for my Satanic outfit.

I was so happy. Was it true? It was! Did I cry for joy? My life would change into something beyond my comprehension.

“Hey!” I cautioned my brothers carrying my cake-box costume. “No more Mr. Nice Guy, me!”

Cloistered in the basement, I spent hours with the package, turning it over, examining each minute detail (Made in Texas!), the caution warnings (suffocation, flammable, not recommended for children under 5 years old!), and did everything but try it on. Not yet, no. It was my first real trophy, and as I removed the elements from the box—the nylon fire pants and shirt, the plastic orange pitchfork, and the mask itself—I was mesmerized. I didn’t dare put on the mask (it was enough to hold it and look at it and think about it, to inhale its wild smell), for fear its powers would dissipate and slip away. Then I’d lovingly pack everything away back into the cake box with its plastic see-through top, the word “Devil” printed in bright relief Hollywood script, something you might see on the flannel shirts of little leaguers.

On the 31st of October, one of those golden autumn days with the red, orange, and yellow leaves piled up high in the sunshine, crackling underfoot, a slight wind breezed through our town. Carved pumpkins dotted the porches of the neighborhood, punctuating the houses with fat orange blots; at night they would be lit, guiding us to candy-filled homes. You could smell the adventure.

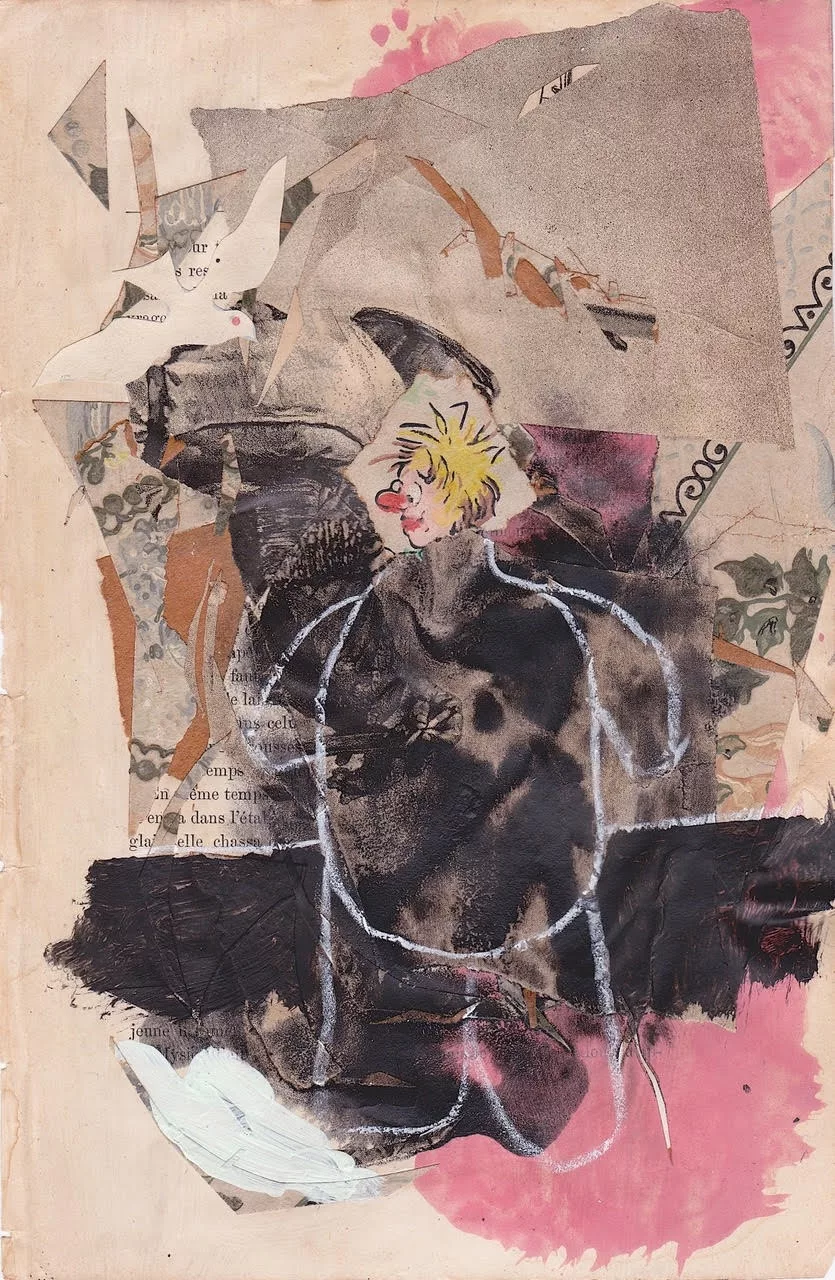

As darkness settled in and we finished dinner, the streetlights came on, and it was time. I descended to the basement with my devil mask and costume box. There, in the laundry room, facing the mirror I had this amazing moment all to myself. Opening this magic box for real and then carefully removing the mask and unfolding the pants and shirt, I held it up to my shoulders, measuring it up against my body. I slipped the pants on over my dungarees and sneakers. With their fiery, swirling whirls the pants and then the shirt offered up a kind of silky welcome mat to Hell: black with pitchforks and the scary face of Vincent Price. All to be tied with red nylon ribbons around my hips. The final touch, the Devil Mask itself, with its elastic strap that snapped to the back of my head. It smelled of something from another world. Plastic! The smell from Hell! While I had a bit of trouble breathing at first – and my eyes somewhat blocked by cutout slits – I saw finally … myself… all dressed up, my devil me in the mirror.

The doorbell began ringing. Trick-or-treaters were now mobbing our house. Halloween was happening, and we had to get out there for the candy corn, Hershey bars, and pennies. But something was wrong, not right; I swallowed hard and studied myself. Who was this person I was looking at. I didn’t recognize myself. I didn’t know who was standing at each end of the reflection; either we were too far apart or now in part two of my dream. But here it came, in a burst, the embarrassment. Followed by shame. I was mortified and didn’t fully understand why. My first epiphany. I began to grieve and to mourn. I began to cry.

And then, there was a wave. I hated this costume, the devil, the plastic, the glaring colors, the me beneath it all, the me that wanted this. I hated it all with an incredible force, with all my might. I busted the plastic strap tearing it off my face.

My mother seemed to sense something was happening to her youngest child, but not what exactly. She called after me from the kitchen upstairs.

“Matthew…! Are you going out? Your brothers are waiting for you… Put on your devil costume! The one you wanted so much!”

My brothers chimed in. “Yeah, let’s see the dopey devil already. Can’t wait”

“In a minute!” I yelled back. “In a minute.”

I wished I were dead. I began to stomp around in circles, alternately slapping myself in the face and calling myself an idiot. My devil outfit, was suddenly a skin I’d outgrown in a season. I ripped the entire business off and crammed it back then tried to crush the box with my hands. What was wrong with me? The doorbell was ding donging. I closed the door to the laundry room. I wanted to crawl into the dryer, and hide forever inside it.

I buried my head into a basket, pushing my face into a stack of fresh bedsheets, smothering my wallowing. The smell of soap and cotton surrounded me. It was then I found the second miracle of my life.

I stood up, unfolded one of the sheets, and draped it over my head. With gargantuan effort, I bit a hole in it with my teeth, and produced a small hole with my poked finger and pulled two of them large enough to make eye holes. I could see well enough to mount the stairs and face my mother, who was busy running to the front door with fists of candy corn. My brothers, dressed like cowboys with toy guns and red bandanas, stood smirking, waiting for their fucked up little brother.

“Okay, yeah,” I sniffled. “I’m ready.”

Matthew Rose’s latest book is 10 Days in Hackney. In it, he writes about moral conflicts of busking with his mandolin in London.