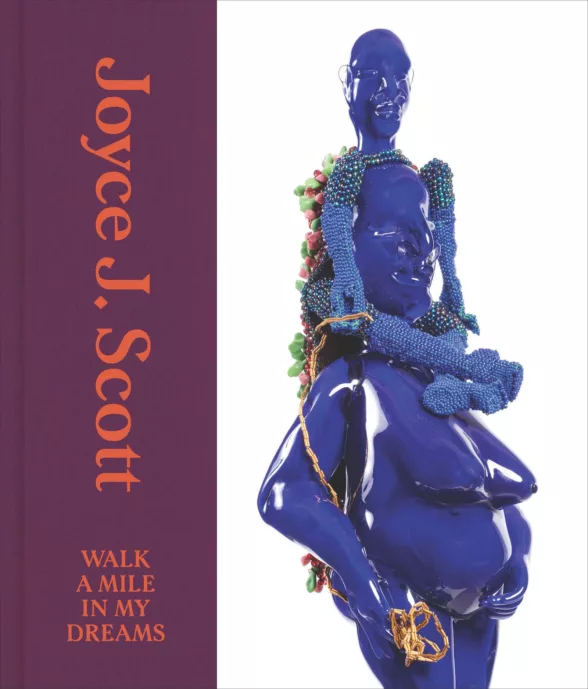

Joyce J. Scott; Walk a Mile in My Dreams (Seattle Art Museum and Baltimore Museum of Art with Yale University Press, New Haven: 2024) ISBN978-0-300-27620-6 $60 – Baltimore Museum of Art

Joyce J. Scott is a singular artist who has developed an unforgettable body of work. This splendid catalog is a survey of her more than fifty-year career and should make it clear that she is a major artist who has made a unique contribution to a revised history of America, warts and all.

Scott is a daughter of inner-city Baltimore, where she collaborated with her mother, a respected quilt-maker, and she has remained in her neighborhood out of loyalty. She works primarily with small glass beads of the most ordinary sort. She has traveled widely and makes reference to international beading traditions, textile crafts, and non-Western belief systems. She moved from making necklaces to figures in the round, adding found objects and hand-blown glass. More recently she has produced densely-figured bead hangings, installations, and large outdoors commissions. None of these descriptions capture the human insight or emotional punch of her work, which has political and often narrative content. In parallel with her sculptural work Scott is also a performance artist.

Scott’s work is exuberant and often satirical (“Buddha gives Basketball to the Ghetto” 1991); it literalizes demeaning sayings and expressions (“Catch a Nigger by His Toe” 1987), and references current events (“Rodney King’s Head Was Squashed Like a Watermelon” 1991). Her subjects include the unspeakable (the 5-part “Day After Rape” series 2008-09) and the unimaginable (“Dead Albino Boy for Sale” from the series “Flayed Tanzanian Albinos” 2021-22). The many essays in the book situate her work within African American and African contexts, discuss traditions of both beads and glass as art materials, record her performance work, acknowledge her role as a collaborator, and reflect how important she has been as a creator of community, teacher, and exemplar for other artists through her work and her personal generosity. The book is beautifully illustrated and gives a remarkably-rounded view of Scott’s position within a community of family, friends, artists, neighbors, and an international community of artists.

Read Susan Isaacs’s review of the 2024 Joyce J. Scott retrospective at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

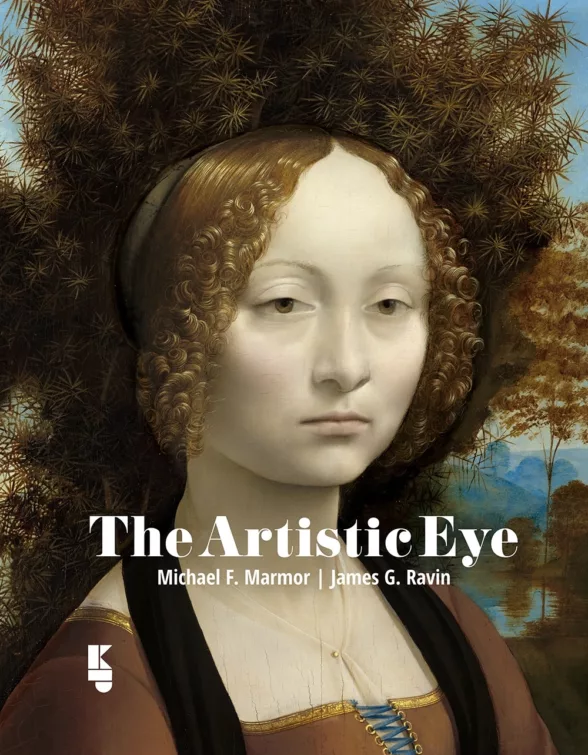

Michael F. Marmor and James G. Raven “The Artistic Eye” (Kugler Publications, Amsterdam: 2023) ISBN 978-90-6299-284-3 Kugler

Anyone serious about looking at paintings will be fascinated by this book. It is written by two ophthalmologists with a long interest in art and many publications on the subject. They discuss the physiology of vision and the extent to which it, as opposed to artistic choice, determines the way an artist sees and represents the world. The book is clearly written and obviously intended for audiences who have no background in the subject, and would be an ideal addition to any bibliography of art history methods.

The book’s examples will be familiar to those who have taken an introductory art history class – as well as autodidacts. There is some emphasis on nineteenth-century French artists, but the book it includes work by Durer, El Greco, Rembrandt, Matisse, and more recent artists such as Bridget Riley and Chuck Close. The authors begin with the often-raised question of whether El Greco elongated his figures as a result of astigmatism, which is a common eye condition (the answer is “no”). They discuss how vision changes with age, with the story of the Classical Greek vase painter, Euphronius, one of their few examples of artworks other than easel paintings and drawings. He was widely known for his work, but abandoned painting in middle age and turned to pottery; Marmor and Raven suggest this was a response to the common condition of aging eyes, presbyopia, a change in the eye’s ability to focus at close range, which is now corrected with reading glasses.

Marmor and Raven cover aspects of normal vision, such as depth perception, and distinguish it from the use of perspective, which is a painting convention that differs according to cultural tradition (which they illustrate with examples from China, Japan and India). They discuss cross-eyed painters, such as Durer and Guercino, who were unable to perceive true depth, but successful in portraying it. They also look at visual illusions, the eye’s ability to perceive light/dark contrast, and color perception, and how artists have made use of them. Paul Henry and Baccio Bandinelli were both color blind, and we are shown how it affected their paintings.

A chapter on the aging eye addresses the fascinating subject of the often-discussed “late style,” and whether it can be explained by visual changes as opposed to changes in dexterity, changing goals or artistic styles. Eye diseases clearly affect an artist’s vision, and the authors explore them at some length, including Degas’ macular disease, Pissarro’s excessive tearing, and the cataracts of Mary Cassat and Monet. They use particularly valuable computer simulations to recreate how Monet would have seen with increasing cataracts and after their surgical removal, as well as examples of his changing paintings throughout the period. They also include Munch’s remarkable drawings and paintings of the effect of his own eye hemorrhage.

Waleria Dorogova and Laura Microulis, eds. “Sonia Delaunay; Living Art” (Bard Graduate Center, New York: 2024) ISBN 9780-300-27576-6 Moe’s Books

This stunning exhibition catalog is a fitting study of an artist whose career has, until now, been seen too often as adjunct to that of her husband, painter Robert Delaunay, and whose work has received divided attention, with her paintings considered in terms of early abstraction in Paris, and her decorative work addressed separately by scholars of fashion and the decorative arts. This is particularly ironic, given that one goal of the avant-garde was the elimination of hierarchies within the arts. Artists’ day jobs have rarely been studied, but Delaunay’s activities in clothing, textile, graphic and interior design were not conducted in support of her work as a painter. Delaunay’s career exemplified the merging of major and minor arts in pursuit of modernity. She conducted all of the work under her own name, and color can be seen as her primary interest across her output.

Delaunay’s work encompassed paintings, murals and prints; advertising posters; book bindings; interior designs, including furniture, textiles, ceramics and rugs; theater and film costumes and sets; clothing design including custom textiles, hats and jewelry; and automobiles. Twenty-three authors analyze a broad range of topics, including her situation as an exile; interest in light, color, and movement; innovative concept of interior design; exploration of art and commerce; and the idea that fashion was a means of spreading the art of living shaped by ideals of the avant-garde.

In 1913 she collaborated with the poet, Blaise Cendrars on “La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France,” a six and a half foot-long fold-out book, whose form and co-authorship both challenged conventions. Tamar Kharatishvili discusses it as an example of Delaunay’s “productive fixation on technologies of modernity.” Kasia Stempniak looks at the artist’s theoretical approach to art and dwelling; she describes how Delaunay’s work “prompts us to reimagine how we think of interior space by destabilizing distinctions between binary oppositions of exterior/interior, flesh/material, and body/building, … “ Rachel Silveri suggests that her commercial projects were of multiple uses to Delaunay: “She used the commercial to advance more broadly the project of Simultanism. She uses it to explore, spread, and popularize new avenues of artistic activity – the store window, the advertisement, the publicity poster.” All of the articles are extensively illustrated, and Irma Boom’s stunning book design is a fitting homage to a great predecessor.

Read more articles by Andrea Kirsh on Artblog.