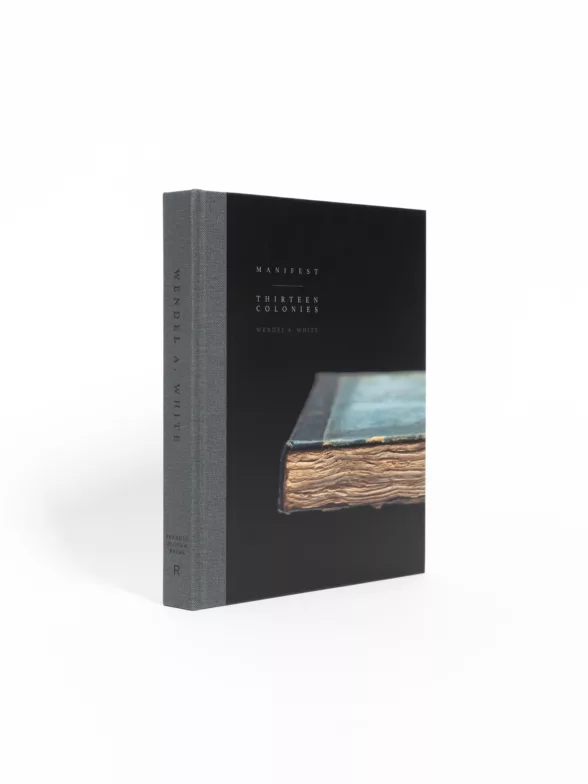

Wendel A. White Manifest: Thirteen Colonies (Radius Books and Peabody Museum Press, Santa Fe and Cambridge, MA: 20024)

ISBN 979-8-89018-085-8 – Hardcover, 9.5 x 11.8 inches – 298 pages / 235 images – $70

Radius Books

Manifest: Thirteen Colonies is the product of almost fifteen years of research, conducted in museums, libraries and historical sites that hold evidence of the African American presence in the thirteen colonies that became the United States and Washington, D.C. Wendel White describes the book as ‘the result of trying to formulate a visual response to the history of race in America.” The design, printing and binding of this large and extremely handsome volume alert the reader to its importance to its publishers, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, where White had a photography fellowship, and Radius Books.

The photographer found himself “increasingly interested in the residual power of the past to inhabit these material remains.” He is not an anthropologist, and the material culture is that of his own heritage. His photographs do not attempt complete, clinical representations of the various artifacts. Rather they represent the photographer’s response to objects that contribute to his personal as well as historical imagination. Manifest is in part an examination of the role of the anthropology and ethnography museum in archiving the material culture of a people, and hence, in contributing to its narrative history. It is equally an exploration of the role of photography in that process.

Collections depend upon what remains, whether by accident or by choice. Some of the objects in Manifest are significant because of their connections to people of historical importance. The image that initiated the entire project shows a lock of Frederick Douglass’s hair, which White found in the collection of the Rush Rhees Library at the University of Rochester. “The experience of direct contact with a remnant of Douglass’s body was powerful and transformative….As one of the most photographed figures of the nineteenth century, his beautiful and striking hair style was very much part of the image he so carefully constructed….making a photograph felt very much like an extension or continuation of his efforts to be seen and represented through the photographic image.”

Other objects, such as slave shackles and collars, or a slave account book, have obvious historical value and contribute concrete, visual illustrations to shameful stories we already know. But some objects are so ordinary that we can only wonder at their survival, such as a pressed corsage, a box of commercial hair straightener, or a pair of handmade children’s socks from a North Carolina plantation. The volume includes several scholarly essays and records of conversations between White and colleagues. White’s photographs are a haunting examination of the search for historical truth, the potential of material culture, and its significance for the present.

Mark: Sonya Kelliher-Combs, Julie Decker, ed. (Anchorage Museum and Hirmer Verlag, Anchorage and Munich: 2024) ISBN 798-3-7774-4254-9 – 240 pages, 220 colour illustrations, 25.4 x 29 cm, 10″ x 11 1/2″ Hardcover, 52.00 (British pounds)

Hirmer Verlag

Sonya Kelliher-Combs‘s art exudes a complex sensuality that is extremely compelling. I sought out this first monograph on the artist because of a single, unforgettable work I had seen in a group exhibition four years ago. “Guarded Secrets” consisted of a group of cocoon-shaped forms made of reindeer and sheep rawhide, each one pierced by multiple porcupine quills. While Kelliher-Combs’s artwork has been exhibited internationally, the opportunity to see it on the East Coast has been limited; the abundance of illustrations in this beautifully-produced book will have to suffice, for me and for others, as an introduction to an extraordinary artist who deserves a much wider audience.

The artist’s output includes paintings, drawings, sculpture and installations. She has also curated exhibitions and been involved in a variety of community-based projects around her home in Anchorage. Kelliher-Combs is of Iñupiaq and Athabascan heritage, and her ancestral traditions and view of the inseparable relationship among human populations, the land, and other life forms is the basis of her life and work. She employs abstract shapes created with multi-layered combinations of both natural and synthetic materials; these include walrus gut, porcupine needles, polar bear fur, human hair, glass beads, paper, various textiles, paints, ink, beeswax, nylon thread and acrylic polymer. Her techniques include traditional beading and sewing and indigenous methods of preparing mammal gut, as well as techniques of her own invention. Regardless of the sources of her materials, the work always refers to the organic and the local.

Kelliher-Combs has largely worked in series, some of which have extended over years; this is consistent with her focus on populations and communities, rather than individuals. A recurring motif takes the shape of a walrus tusk, and it appears at multiple scales. At its smallest, it refers to small pouches worn at the collar of Iñupiaq parkas, that empower the wearer. Kelliher-Combs has turned these small pockets into metaphors of secrets, representing the pain and feelings of shame of indigenous populations who have had to deal with generations of abuse at the hands of settlers, their schools and churches. The serial forms and layered compositions speak to the amount of handwork that went into each artwork and by analogy, to the depth of history and emotion embedded within it. Her art attests to cultural endurance and creativity, as well as pain. Whatever ideas she includes that may only be understood by her own people, her richly-human art offers a great deal to all audiences.

Read Part 1 of Andrea Kirsh’s 2024 Books for Holiday Giving.