I followed my best friend to a narrow threshold, in place of a doorknob there was a wrench. We entered a dark stair and he explained the lightbulb was torn out, but if I fall he’ll catch me. I carefully stepped across a basement cluttered with weird shapes, lifting my feet and walking slowly past an exposed saw blade, shuffling through another passage, and emerged into a murky world. There are baskets with long necks and flat faces, melting books, spindly wooden arthropods on their backs, mechanisms at rest, as well as several puddles of evaporating liquid. All are instruments of measurement that are unmoving, but still recording.

This has happened before – I follow Jim on an uncertain path, we end somewhere beautiful and strange. Jim Strong is a painter, musician, curator, and artist based in the Philadelphia area. We both joined Vox Populi Gallery as artist members in 2016. One night soon after that he called me and asked if I would play a show with him and I had 15 minutes to decide. I said yes. We have many years of deep friendship and joyous collaboration spent together, including our band Saggy, both an expression and tool of our friendship, trying through experiments in pop music, poetry, and wet rocks, to remain in the present.

In September, on the eve of his album My Enemies Are Mine to Keep, released on vinyl through Horn of Plenty Records, we met at his studio in his family home. Through transcription and narration, I will strive to capture our conversation and impart some of my observations of my friend.

He began by showing me his newest evaporations, a self-devised method of painting he refers to as recording. Jim writes, “Painting as recording foregoes traditional mark-making to observe the concentrating effects of time, evaporation and gravity as a means of latent image processing.” These are the puddles, pools of paint poured on molds slowly evaporating in his basement studio. After waiting between a few days to several months, they may be built into intricately carved or woven frames. They have the effect of something old and odd, artifacts of an environmental memory with a swimming reflection each with its own story or song.

Jim Strong: Once I start introducing multiple layers, the surface opens in a way that it can be hard to have the finality of. I have a few here where I’ve done that, occasionally it works in a way that closes it. There’s a hermetically sealed quality that I like in the evaporations where they’re just a singular field.

Lane Speidel: Do you mean open the surface physically? Or open the surface visually?

Jim: I think when you start adding new layers, it creates painterly choices that take it out of like the strange thing that it is, which is not quite the thing where I’m in there making gestural choices. The gesture is finished in their first skin. It’s all contained in one layer. Like this, (referring to another evaporation) there’s a lot of gesture that came through because I’ll drop pigment and different things in from the backside, but then it’s all one thing. And that’s the goal, is to have a unity.

Lane: It’s as if it’s born.

Jim: If I start going in there and playing with it every time I’m doing that, it’s getting further away from this process that has a magical chance quality to it. But I’m open to perverting it to a degree, hiding gesture.

Lane: So it’s purity versus perversion. You like both, though.

Jim: I’m after purity. And I myself am perverse. Which maybe says more also about my theological underpinnings as well.

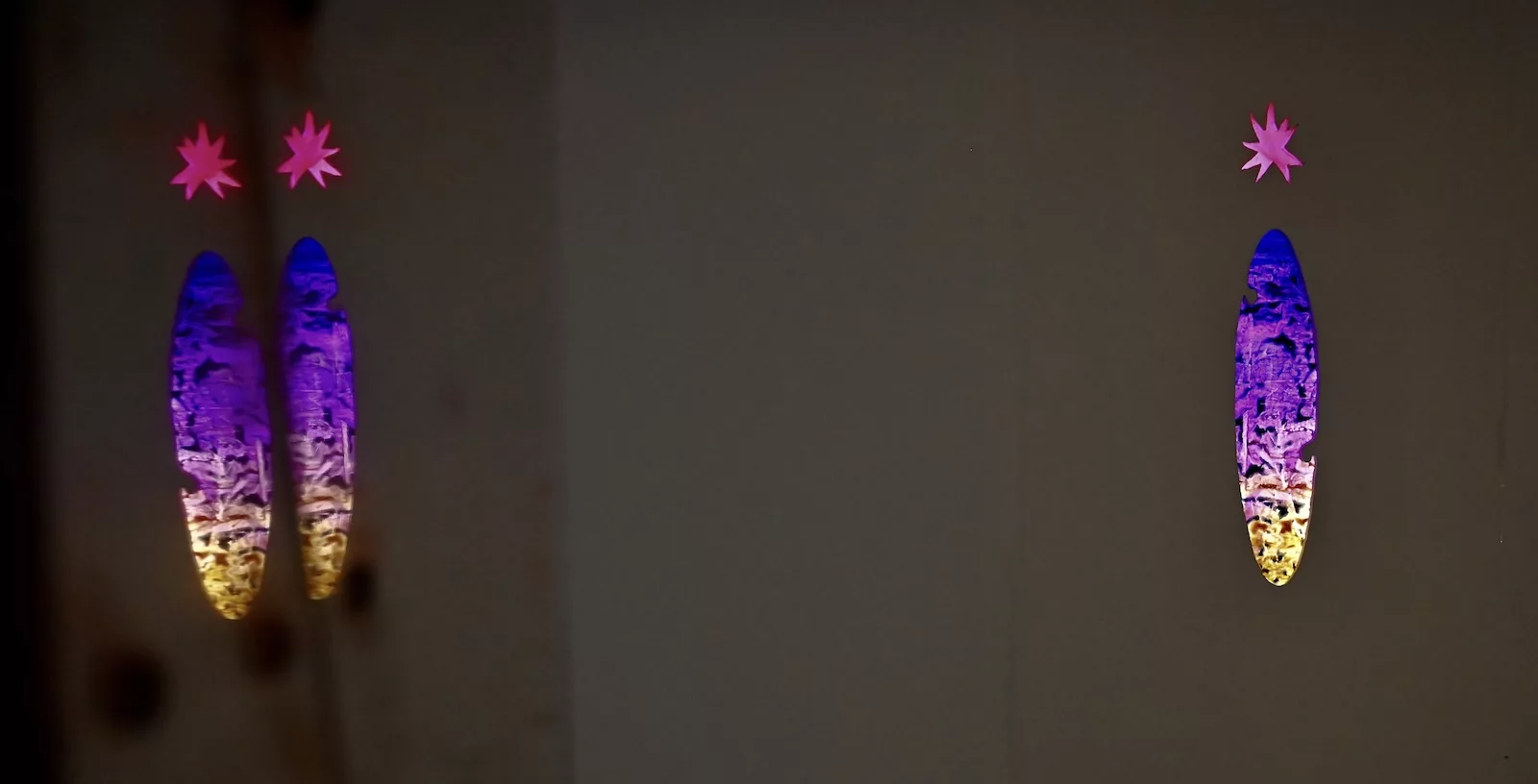

Photo by Jim Strong

Lane: Where does the text come from that you work with?

Jim: Usually it’s excerpts from poems that I’ve written. The poems I feel the best about are the ones that I wake up in the middle of the night and they’re already a little bit formed. It’s usually been integrated through sleep and dreams, but sometimes just through mis-remembrances with asynchronous notes next to each other. They’re never direct. Somewhere the narrative of the dream is getting in but it’s never just pure. It always needs to be… altered somehow. Editing is very important to me. There’s a spontaneous generative thing when you start to sit down and parse through the elements, which I guess is in direct contrast to what I said about the paintings.

Lane: Then you make these elaborate frames and scenarios, stage sets for the paintings. Framing is like editing as well.

Jim: The whole practice has evolved as a devotional sort of waiting project. You’re waiting for these skins to develop and evaporate. Especially when I was first starting, I would evaporate them in open drawers of my clothing drawers. And all through my attic in my bedroom, cultivating a quality of that space where they were evaporated. And I’ll write the time and date, temperature, and any notable things about that moment. As if I’m trying to record an encounter with a species that’s happening in the process.

Lane: That reminds me a little bit of this family story. My grandma was an avid Scrabble player. She’s since died, and they have her Scrabble set with all of the score sheets from years and years still in there, and my uncle would often keep score. My uncle is an archivist and librarian, and he would write the day, the time, the weather, and all of these other factors. I thought you would appreciate that because I think your family and your family home and all of the various legends and accouterments are present in your work.

Jim: I hope so because there’s so much of the practice that I don’t have control over by design, I think that’s something that takes on an almost desperate quality for me of wanting to communicate that, that my friends and family are in the work and what it’s about.

Lane: The first time I saw your home and stepped into your house, I could see more of you. It’s a fundamental part of you that walks around with you that I have never seen. It illustrated you further to me.

Jim: For better or worse, this is my lot. This particular home is the place where my dad grew up and his brothers lived. It’s filled with ghosts. And it was formerly exorcized in the mid-Eighties because there was a spirit that would come and lie down on you while you were sleeping.

I saw things when I would come to visit my grandpa when he lived there. Especially down here in the basement where I work, I always thought that was interesting because I live at peace with them in some way. There is a shadow work component of living in your family home and living with family… watching them age and the biggest fear in the world is that something will happen to them, but you’re also waiting.

I think maybe people who move away from all of their family have a different relationship because they come back and they see the aging process. I feel like I’m always waiting. I’m listening outside my father’s door and participating in that practice. Granny passed away in this house. Grandpa spent his last years here. In some ways, they’re still here.

Lane: I see your home as a museum where things are only added. For instance your grandmother’s collection of owls. Never subtracted, only added. And I think that’s beautiful, that your paintings are a cast of this environment.

Jim: They’re recordings, both of what they are, but also of the location where they were conceived. And in that same regard, the ghosts are present and some of the ghosts are very scary.

The religion of art holds both the devotional and the trans-material qualities of the spirit life and also the sensual and energetic qualities of what might be associated with darker realms. But I think many of the spirits that might frighten us at first are scared and that’s why they appear to us in this sort of manic intense way. So I think it’s good to look at them with empathy and also from a place of peace and not being afraid.

Lane: Definitely. I was thinking about your attic and your basement and how I was so incredibly afraid of my basement as a kid. And thinking about if I wandered into this room as a child with the dim lights and all these wild images and sculptures…I would have been really scared at first.

Jim: Oh, I was very frightened of this basement. In there is a very ancient furnace and it shakes the entire house when it turns on. There’s a window where you can see the fire inside of it. My cousin said that there was a demon living there, and when it was off, the demon was in the house. We mostly live without heat in the winter months so then it’s always off.

Lane: So it’s always in the house, it’s always loose. There is a Russian folkloric belief of the spirit that’s in the stove, the Domovoy, and you have to give little offerings to the spirit, so he protects your house and keeps your house warm.

Jim: Celtic fairy lore is exactly that way, you have to leave an offering, or you’re cursed, and you tread very lightly past the fairy circles. Fairies would try to trick people by making them eat special little foods. And when they’ve eaten the food, then they would be part of the fairyland. They could never return home.

Lane: Yes. Or drinking from the stream of forgetting. And never being able to remember who they are. There’s always a trick to it, versus if they said “Hey, do you want to live forever?”

Jim: There is always a transaction. I like to think of the fairy stories where people are tricked to leave their own world for an afternoon and hundreds of years pass until they can return home and everyone’s gone who they know.

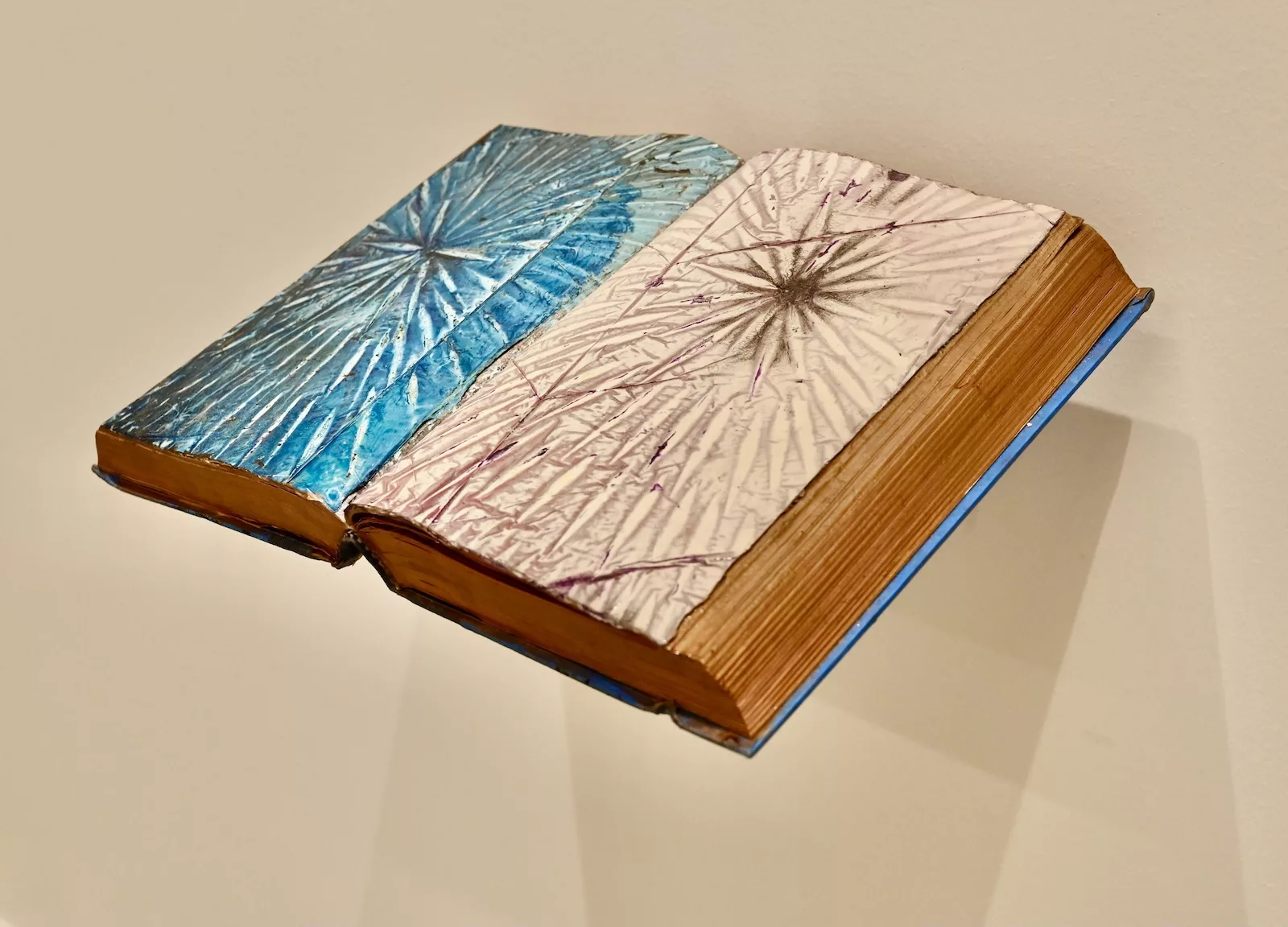

Every Person is a Book About God was an exhibition that Jim installed in a gallery in the Anderson Hall building on the former UArts campus. As an alum of the painting department, it was a major goal of his to exhibit work there. The show featured book paintings, floating and open for the viewer to fall into starbursts of color.

Lane: I was just wondering, because a book implies sequence, and when you do your evaporations on a book, you’re freezing it in time.

Jim: That’s very interesting. The book works that I have done are the portal of the imagination of reading, you go to a different place when you read a book. You get to a point in reading where you are in a trance and forget that you are reading and you’re just seeing pictures. It’s like a doorway, the book itself is the frame and you’re passing through it into the open field of the evaporated form.

We moved over to a part of his studio where he tinkers with his ever-expanding collection of homemade musical instruments. Made of wood and string and motors and tubes, they are largely difficult to decipher visually and hard to recognize from sound alone.

Jim: These are some of the instruments on the new album.

Lane: Oh, cool.

Jim: This is the drum machine, all the drum sounds are motors. This is an air pump that goes to this flute, so it’s a mouthless flute.

Lane: That’s an old favorite. (referring to an instrument)

The instrument I was pointing to is worn strapped to the chest. Made of wood and surrounded by jointed finger-like stringed attachments it is an oscillating palm with a grasping hand. Strong’s haptic pop album, “My Enemies are Mine to Keep” was released on September 27. It features many instruments invented by Jim to paint a landscape of something outside our present existence but somehow reachable. There are some known sounds, but more often are things that slip definition, what might be a frog or a horn, the rattling of a door handle, or the stolid footsteps of an upstairs neighbor. All hypotheticals percuss alongside tones sweetly menacing. Every time I listen, it’s a process of opening and letting in and deeper in.

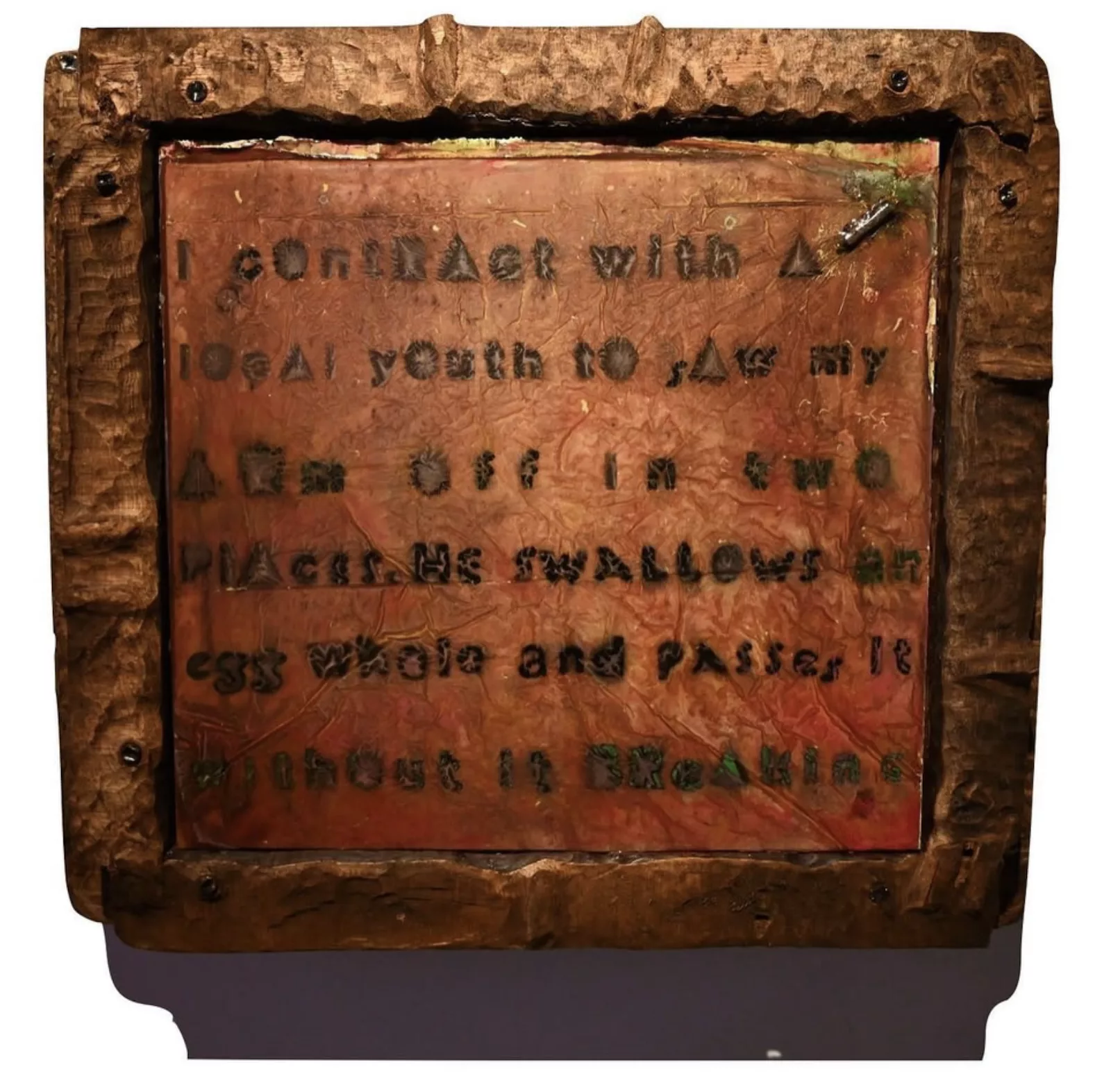

It recalls a painting of his – “I contract with a local youth to saw my arm off in two places. He swallows an egg whole and passes it without it breaking.” (2023). A story with a short list of characters, “he” and “I”, with no morals and broad symbols, consensual violence, and murky wisdom. Something impossible but strangely true.

Jim: There are many evolutions of this one and many more to come. When I first thought of this, it was… a dream where I woke up with that image of someone having a hand on their chest. And it was almost like a horseshoe crab. That’s why I want to do one someday where I work with a special effects artist to create a mold that goes perfectly into my skin. So it’s like a vacuum seal prosthetic woven into my skin.

Lane: Wow. I think there’s a lot of skin-like surfaces. (Pause) Do you want to go outside? Can we go for a walk?

We left Jim’s house by the back door and walked through the woods surrounding his house which has a path leading to a nearby park. We walked side by side in the suburban neighborhoods arriving at the Quaker Meeting House – where Jim attends weekly worship – through the graveyard, stopped by a fig tree, and then walked back to his house.

Lane: I wanted to talk to you about birth and insemination… you said, the works, the paintings had been conceived. So I wanted to ask you about conception as well as waiting and patience.

Jim: In waiting worship in Quakerism or just contemplative prayer you’re waiting to receive. And I always liked that in Quakerism, its expectant waiting. You’re expecting at any moment, in all sincerity, that a very beautiful kind of communion can be present. And logically we know that it is present, but you’re waiting to pass through the brain component of that into the heart space of recognizing the pregnant moment that already is here.

All of reality is in that process of giving birth, and we’re still being born. And so waiting is … like the primordial stasis where conception occurs. Waiting is the edge.

Lane: Waiting is part of your object-based practice, but also inherently part of your music practice as well, because a lot of it is about improvisation.

Jim: I’ve realized a Cancerian quality in my approach to putting work into the world because it’s always from the side, scuttling sideways toward the goal. And it could take many years. I’m still just now digitizing work that I did about 20 years ago that has never been released, and it’s musically the most important work I’ve ever done. Most of what I’ve ever done— painting, art, has never been exhibited or released or anything. There’s a waiting process there, it’s like aging, it needs to take on a little bit of the patina of time.

Lane: I know you’ve expressed both the willingness to wait, but you’re also wanting more of your work to be seen.

Jim: Oh yeah, I think there’s the equilibrium between those two things, desiring the entire world and also refusing it. I think those are the two aspects of the way my practice is also very hermetic and rooted in time, and yet part of it is inherently always the desperation to move through it.

But you can’t skip the steps. I believe very strongly in commitment, committing to a way of working, committing to ideas, and to friends and family. But you hold with it also the intense desire to like, burn through all of it and go to the end, but you can’t get to the end, without the steps.

Lane: Could you talk about when you committed to this practice of painting through evaporation?

Jim: I would say now it’s about fifteen years I’ve been focused on this one way of working and all the time wish I could stop and just make a normal painting with a brush. I guess I could but I’ve already made that promise, it just never feels right unless I’m working in this manner. I’ve condensed to its most basic form of cultivating these evaporated skins that have just trace elements of text and image.

When it first began, I was trash-picking house paint, and making giant sculptural paintings that were composed exclusively of paint. And those would take… at least a year of just layering the paint on before you could see the form. They have a lot of the same qualities as the evaporation paintings, but now everything is reduced to its thinnest possible film. I think that was also to take more of a graphic quality because it preserves the line and the fluidity much more.

Lane: Was there a specific moment or day when you said to yourself, “This is my practice. I have to go this way?”

Jim: I think it was a slow process that was rooted in a love of the history of painting. And being interested in artists like Albert Pinkham Ryder who, as the story goes, would paint the same painting from when he was sixteen up until when he died like maybe in his seventies. His neighbors and friends would sneak into his studio and steal paintings because they knew he would just keep painting on them.

I love the “Ryder method”… painting is a war with time or something aloof from the materiality of time. It’s a life practice, it’s your entire life. If you see Ryder’s work, it looks like it’s just this natural object like a mushroom that’s just grown through the surface. There’s also a separation of the work from the doing of it, removing the hand and allowing more of a system to play out.

Lane: Could you talk more about your interest in the history of painting and the education that came from that?

Jim: I think my earliest education with painting was through my grandfather, Kenneth Canfield, who I did not know so well. I only met him a handful of times in his whole life because I was somewhat estranged from that side of the family as a child because of my parent’s divorce. He was a journalist, a teacher, and a gallerist and he would send me many lengthy letters, newspaper clippings, and art books.

He ran Canfield Gallery out of his living room in the Eighties. He paid special attention to the Taos modernists and the transcendental painters group. His gallery exhibited Agnes Pelton, Oli Sihvonen, Jorge Fick, and even early works by Agnes Martin. I was very young when this was happening so these were influences that worked on me slowly as I was growing up mostly through cherished marginalia, not through any inherited art.

Lane: To ground a little bit in place and time and history, you studied painting at UArts…

Jim: I feel very lucky because I had some very inspiring teachers many of whom were approaching the end of their careers and would retire… several have since passed away. Their teaching methods could be very severe but had a deep authenticity and dedication rooted in their long years of working and teaching which had little to do with the commercial art market. Gerry Herdman, Francis Tucker, Gerald Nichols, Eileen Neff, and David Kettner were all important teachers for me. I remain indebted… in both senses of the word, to my teachers and fellow students.

Lane: And you were already experimenting with systems of removing one tool or another by painting with your eyes closed.

Jim: Yes. I was very interested in invented rituals for having a sort of altered state of consciousness.

So that involved painting with my eyes closed. It was around the time I first tried psychedelics… and maybe it was also getting interested in religion and attempting to make paintings that had a quality of numinous, or inward glowing. The eyes closed paintings were the last series that I worked on before discovering what would lead to the evaporation paintings. That feels so ancient and almost like a lifetime removed because after I got out of school, it was the 2008 financial crisis. I was also deeply depressed and I spent many years just feeling very alone and working and just staying up all night and walking on train tracks, wandering and having that experience where everything is just whittling down to nothing.

I had these paintings I would work on for so long, for like months and months, and then just clap them in half. They’re like these brittle, weird skins. I had a very destructive attitude towards a lot of work during that period and not just my belongings but myself too.

It was a long time that was like a necessary process of discovering oneself and your life and reconnecting with what you want your life to be. I think then the painting and the art really picked up after that. But before that, I just felt like I was an egg. I had not quite developed sentience.

Lane: I think you still honor that state though. Always an egg. Always being born. The numinous, inward light quality of the life inside of the egg. It’s like the eggshell not being just an object or a rock. You do have this deep inward practice, but you’re also very based in external practices of communal music making and you’re always in community, seeing other people’s work, having long conversations, visiting studios… where’s the bridge between that solitary kind of period and this external one?

Jim: They exist simultaneously and also in some degree of contradiction to each other. Because I do feel like a very private person. And some aspects of that are rooted in that quality of isolation, a warm, good isolation.

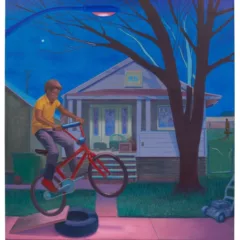

But, that has to be wedded with the world in some way. It’s somehow always been a part of my practice, whether it’s in starting a record label, publishing different things, booking shows, or curating exhibitions. When I was a little kid, I would make these clubs and I had a close encounters club where I would go around and interview neighbors who had seen UFOs. I also had a comic book club. I always wanted people to join me but no one ever did. I’m involved in these networks out of faith in a community that can feel sincere and also rooted in a quality outside of time, to know someone which is eternal.

But that’s the rare and special quality of friendship, it’s constant, and it’s not always a given. So we need to find relationships…they make a bridge into the streaming of time in that way. That needs to be celebrated and it finds its way into the work that is rooted in the private.

Lane: That gets back to what we were saying at the very beginning about making work that’s about your friends and family. One of our main collaborations, our band Saggy, is an expression of our friendship and an observation of our friendship.

Jim: Saggy very explicitly mythologizes friendship, but I view all of my musical collaborations as a chance to mark specific times and places and relationships. That kind of daily myth-making is a chance to insert untruths that are magical and inevitably true.

Lane: More than true.

Jim: Yes, they’re more than true. Super realism. As Andre Breton said, surrealism was super-realism.

Lane: We began collaborating through our mutual membership of what you might call a club, Vox Populi Gallery. And I remember we hadn’t seen each other for some months because of the pandemic. I think we used Saggy as an excuse or as a reason to meet up when it felt like there needed to be a distinct important purpose to be together.

But now we’re at your Quaker meeting house, right?

Jim: Yes, we’re in the graveyard. Which is where many important things are happening. Life and rites of passage have occurred here. I would come here at night quite frequently by myself. I would tense up every muscle in my body and walk during the full moon, in the very magnetic space of this old graveyard where most of the graves are.

There are significantly more people buried here than you see headstones.

Lane: Oh, is that..why is that?

Jim: I think early Friends had a suspicion about the hubris of the headstone. When the soul dies, the body is just a natural material and you can put it anywhere you like. I don’t know if that’s historically accurate…that’s always been my interpretation.

Lane: I remember you told me that you wanted to be buried in the ground and have a fruit tree grow out of your grave.

Jim: I didn’t see “mention the fruit tree” in your notes.

Lane: You have such a deep and sincerely solitary solo practice in a lot of ways, and you also are an artist with a vast number of collaborations. Could you name some of your collaborations?

Jim: Saggy, my collaboration with you is the main one that is artistic, although we’re a band too. Besides Saggy other musical groups I’ve been involved with include Melkings, Builtbyscriabin, Aponia AD, early iterations of Weyes Blood, and Eyes of the Amaryllis… I’m very interested in anonymous works and creating things by myself or with other people that have no entity identification.

Lane: No name, no beginning, no end.

Jim: I did a tape with my cats. A friend of a friend’s grandfather passed away and they needed to put his piano that he played every night somewhere. I offered to take it and give it a good home. We already had another piano in that room and then an organ. I felt an urge to arrange all of the instruments in a single line like a connected bridge. That night we heard these long alien piano pieces playing over and over again – we came down to find our cats walking back and forth in a sort of trance. That’s the tape.

Lane: I think that’s so beautiful, you do have this kind of magic room in a magic house full of beautiful, old somewhat working, somewhat not working instruments. And you wait and observe for collaborations to occur.

——

In this special room, the shiest of all people will find themselves crashing cymbals and shouting into a microphone. This room is a part of Jim’s house and is also a gallery, The Johannes Kelpius Center for the Emerging Arts, which has hosted many art and music shows and performances. Pianos line the walls and practically any kind of instrument is somewhere in their child or adult size. As well as many things you didn’t recognize as instruments at all. It is a very special, nourishing room. Jim and I started walking back toward his house.

Jim: I’m very able to disappear sometimes into the group, which is what you want, I think. You want a kind of a new thing to emerge and not to just be doing the same thing that I would be doing if I was by myself. So all of those projects are very different and my role in them is always shifting.

I used to be more involved in the free improvisation community where you would have these ad hoc performances. And there’s something about that I love, and I learned how to play with people doing that. But there was a promiscuousness to that thing that actually hurt my feelings a little bit. My partners could play with me, but they might just as well be playing with anyone else, and they would be doing the same thing. Regardless of whether I was there or not.

I much prefer these sorts of very intentional projects that are really trying to create a new group identity that honors a relationship and a specific place in our lives. Friendship is such a beautiful and mysterious thing to me. I am continually perplexed by it. All of the complexities that compose our relationships should be visible in the project. They make it more beautiful even while those tensions are unraveling the collaboration.

And then sometimes they have to be left aside for a time or all together. Not all friendships or projects last forever.

Lane: Except for this one project you have with your friend Daniel Fishkin where you’ve committed to playing together once a year.

Jim: Yes, that’s right. I remember we made that pact before playing at the Red Room in Baltimore. The affirmation came for me out of mourning the loss of another long-time friendship… I wanted to be very intentional and make a real promise to Daniel, and to other partners I choose to work with. It means a lot to me to still be playing with old friends like Daniel and yourself and bringing these deep friendships with their complexity into the present through renewed collaboration.

My new album closes with a duet with Natalie Mering. Natalie and I collaborated closely throughout the early-mid Aught’s in her project Weyes Blood along with Jordan Burgis… and with our duo League of the Divine Wind, the Scrotum Bells, and countless other collective experiments. It seemed like there was a renaissance of Philadelphia DIY happening then. A lot of it for me centered around house venues like The Haunted Cream Egg, Big Pink, and the Avant Gentlemen’s Lodge. I really wasn’t thinking about releasing music at the time. We would have these very temporal private installations in each other’s houses where we would perform plays, be in bands, exhibit paintings…

Lane: Do you want to talk about your experience exhibiting your objects? What you would like for your sculptures and paintings in the future?

Jim: I would be interested in showing in sacred spaces, and homes but less and less in the cube of the gallery. I think it’s been a learning process trying to integrate into the exhibition cycle at Vox Populi. The speed of that and the default to utility and simplification that requires.

This is the life I want, I want to be showing work. Ultimately, I do want the work to be in a sanctuary for expanded time and where it doesn’t feel like everything just starts over every month. My dream is to someday operate my own space which would be more of a cabinet of curiosities, where you have these ongoing entropic additions that, are always changing but always the same as well.

Lane: That’s what your house feels like to me.

Jim: That’s where the work is coming from, so it can feel very counterintuitive to put that into more of a traditional gallery context, where it’s just always changing, “What’s the next thing? What’s the next thing?” It might take years to make a painting, and then it’s not just over the first time you see it, because paintings are compressed time, they take time for the information that’s contained in them to come out.

I do think that viewing painting requires some kind of commitment. In my last show at Vox, Transcribing a Wilderness, we had a meeting for worship in the gallery space and that’s something I’ve done at the gallery on a couple of different occasions in which there have been up to three hours of just sitting in silence, often open-eyed perceiving what’s around us.

Lane: That’s beautiful.

Jim: I think I’d like to join a monastery. My desires don’t fit neatly into any church nor in music or gallery spaces. The person that I am becoming… does not belong to any of those worlds. So I feel pulled between many different conflicting tendencies as an individual in the world but also as an artist. Trying to find those rare friends who can accompany me… and I can accompany them. This becomes this diabolical mission.

(Lane laughs)

Lane: I want to ask you more about your solo album, My Enemies Are Mine to Keep.

Jim: I sent my record out to My friend Simon, who lives in New Zealand, he does a zine called What Lies Beneath. And I loved what he said about it. He said that it is a record that has no sense of gravity, and just seems like it’s not from this world. And I thought that was very sweet. I don’t know that they were meant as compliments, but it was very nice to hear.

As I write this I’m listening to My Enemies Are Mine to Keep

The first few tracks of the album are a gentle tap at the threshold, a fairy tale entrant whispering and scraping the door jamb. All promises are convincing although the phrases do not cohere and the effects are unknown. In “Open a Wax Star” the doorbell is elbowed repeatedly with building creaking strings, insisting entry upon the aural door, each song refusing to comfort me about what happens when I open up. In the following tracks, the door is wide open and swinging on its hinges – inside a daydream nightmare folktale. “ ’til Morning Jogger Prods with Stick” passes us through grinding bones into a sickly greenish dawn beach. Piercing and scraping signals a puncture, discord has been measured. The latter half of the album gathers in accord. The title track is a lovely, howling lullaby filled with wind and saws and a tender kiss on the forehead with a bloody mouth. The opening of “We Eat the Things that People Say” displays a lovely melody that seems to fall off a butter knife. Like all delicious things, it is swarmed by flies. The tracks slowly overtake, until the foreground is full with the chorus between Jim and Weyes Blood in the last song “The Measure”. The vocals have been growing as if the musician and his instruments are steadily approaching on a distant country hillside, we can hear them coming and see them in the distance long before they have gathered at our doorstep to sing.

Jim: This is my first-ever solo vinyl LP, which is a milestone, it’s been released by Horn of Plenty, which is a record company in the UK that I’ve worked with on other projects.

It feels like the most complete work I’ve had to this point. It’s conceived in this quality of haunted privacy that comes from home recording, but then it wants so desperately to be like a grandiose pop album. It is almost there, but I just simply don’t have the means to do that, so I think it’s a record caught in the middle of these warring intentions of public and private, and grandiosity and miniscule.

Lane: It sounds like it’s a synthesis of a lot of things going on in your practice, in your life.

Jim: It’s all made with homemade musical instruments that are built in tandem with the paintings, usually with the same materials as the frames are made out of. And so the world, it’s painterly. It’s maybe more where I get my painting in than in my actual painting process.

Lane: Do you record with your paintings too?

Jim: They’re always watching. It’s part of the gestation.

Lane: I wanted to ask you about the importance of food and the body and organs in your work because at your events you’ll have a kind of cocktail or strange food. You’ve done events at Vox about the endocrine system, for example.

Jim: This is a newer focus for me. It’s slowly starting to get in touch with the varying and contradictory aspects of health and tension and equilibrium, tightness, and fluidity of the body. Art which has denied the body is an impossibility. I think the existence of art and poetry has always proven to be more complicated than the duality of mind or body. I’m working on a series of diagrammatic text paintings about some of these subjects.

We have extrasensory qualities that are coming from these different parts of our body. You’re progressively knowing a little bit more and a little bit more. Learning what the path is and what you have always been moving towards without knowing it.

Lane: And here we have come to a path to your door.

We arrived at the front of Jim’s house, crossed a small stream, and trudged uphill. We agreed that the interview was over and marched back into the house – triumphant and slightly sweaty from our task. We found our partners together laughing with books of poetry in their laps. We asked what they were laughing about, they said they didn’t know.

Listen to his Jim Strong’s album My Enemies are Mine to Keep, available on record, bandcamp or Spotify, and they can see his paintings in person at the newly opened show Becoming a Field at Automat Gallery, a group show curated by Kimi Pryor, open now til Nov. 23, 2024.

Read more articles by Lane Speidel on Artblog.