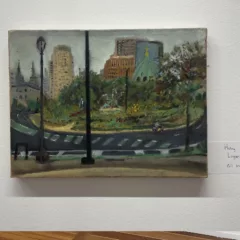

Larry shares his house with his partner Liz Heller. It’s a house packed with art from floor to ceiling. Climbing the stairs to his third floor studio is like a tour through a salon-style museum; image after image, scene after scene. There are so many paintings – by Larry and Liz – that you want to spend time with, where you can smell the air and feel the sun. Places you seem to know and can almost remember. Our conversation started as we stopped at a particular painting.

Pete Sparber: I need just a moment to look. I saw this one on the web.

Larry Francis: Yeah, I think I posted it. I have a half size version. I’m doing a few versions of this house.

Pete: This one is complete?

Larry: Pretty much. You never know. Everything here needs a little more work.

Progressing to the third floor studio we focused on a painting that looked finished. Then I noticed that photos of two figures in the painting were taped to the surface.

Larry: Yeah. The figures are almost always from photos, and the landscape is almost always done on site. People walk by and I take photos. Sometimes people migrate from different areas.

Pete: I see how you’re placing them. There’s the quality of the figures where they’re taken from one world and put into this one. They take their interior life with them.

Larry: Yeah. I’ve developed these narratives and then I put figures in, and sometimes the quality of light is different. I can show you one that’s from the past. That’s my car; then this other car showed up and I liked the color. The figures came later. It was this idea of people meeting. Originally they were photographed in Rittenhouse. I lived on 20th Street for a while. I would do these seven foot paintings in the park. That was fun, but dealing with the wind…especially large canvases.

Pete: Yeah, they can take flight.

I wanted to discuss this quality that I see in Larry’s work. When I look at his paintings I feel like I’ve been there… that I have a memory of the place. Listening to Larry’s history and creative process a viewer begins to get a sense of how that sensibility emerged.

Larry: I’ve always painted places I know. I painted Yokum Street where I grew up in Southwest Philly. All my relatives lived there. It was a small street. Nine houses and seven of them were relatives, and their yards were (connected). There was a junkyard across the street. My dad had a bike shop. My uncles and aunts lived there. My uncle and aunt had chickens for a while. They had a goat…right in the middle of the city. I think it was a special place to grow up. I painted that a lot. I painted the yards, the houses. They were all very familiar. And I actually lived on that street until about six years ago.

Pete: Immersed in all this family.

Larry: Yeah. My family slowly left. There was only one cousin when I finally left. So, all that changed. My family was there for five generations. I’m a city person. There’s all this wonderful stuff when you paint out in the street, especially among people that don’t go to museums. People are so happy to see someone creating. There’s always that thing that goes on with people just being interested. I’m trying to do the best I can and (I find that) people love it. I think that’s my job. I put together shows and, in that way, make my way through the world. And there’s being in a place every day for a month. You become more engaged and things happen that add to the work. Sometimes when I’m doing one painting I see the painting I should be doing…I’ll see something else about it. There are scenes that I go back to…to make a better version. I’ll ride around all day looking. I have a catalog of places that I’ve thought about. Plus I study other artists. This morning I was looking at Hopper, John Sloan and the Ashcan painters. I always think of myself as sort of an Ashcan painter. It’s painting the city. There are a couple painters that lived in this area in the thirties, forties and fifties and did urban painting. (Collectors) would buy Bucks County paintings of the pastoral landscape. I don’t want to do pastoral landscapes… (rather) the urban environment.

Pete: The city engages you. Maybe living out here (in Manayunk), it’s where the city meets nature.

Larry: Yeah. When I do paintings of the river it’s more pastoral. Or when I painted Rittenhouse Square, to me, that was pastoral painting.

Pete: Absolutely, Looking at these (Larry’s suburban landscapes), the way the light hits the buildings and the sky and the feeling of the shaded trees. You said one thing that really stuck in my brain, that you see it as your job. I want to make sure I understand what you meant.

Larry: Well, when I was young I remember going out in the street and being a painter. I thought ‘What kind of activity is this?’ I was a little embarrassed. But, after a while, it was more like a magic act. You go out in the street, you set up. It might be just wanting a little round of applause, but when people engage, it seems like it’s not about commerce. It’s just about doing the art and having people see it. Then there’s the life problem of how are you going to make your way? By that I mean the feeling of why you’re doing it. You’re trying to show the world you’ve been in. I’ve painted in Northeast Philly, Fifth (Street) and above, and Allegheny. But I’ve always thought of myself as a representative of Southwest Philly. And when I started landscape painting it was at the height of the academy. Then landscape painting seemed to go away for a while. Like everything it receded and then came back. There are a lot of younger people who are painting the city. I see more of them than I used to.

Pete: Yeah. There are some good ones out there now.

Early Influences

Pete: Was there art in the family? Where did this all begin?

Larry: Well, not in a museum. My dad was a craftsman. He had a bicycle and hobby shop. He built model airplanes and made little train platforms for the shop window. He could draw. But my folks never went to a museum. He was very visual and mechanical and good with his hands. When I grew up I worked in the shop repairing bikes. My mom had a visual sense too. I was in the hospital for a couple years when I was a child and I got behind in school. I did draw cartoons, and between seven years old and nine I would draw buildings.

Pete: I’ve noticed that when people are young and end up in the hospital or being bedridden for a while that can set off a creative impulse. Was that happening?

Larry: Yeah, I think that might have happened. The most fun thing was looking at and reading comic books. I was in a great place…the Children’s Seashore House, in Atlantic City, right on the boardwalk. I was there for two years. (I had a) hip joint disease. That’s the way they handled it back then. They would take the pressure off your leg. I knew somebody who had it, who became a friend, who (now) has a big lift on his shoe. He left the hospital early and the joint degraded. It’s like the Buddhist story..that was a bad thing that happened. But then, later in life, it became a good thing. It goes on and on. I became a gymnast and always wondered if my legs were under developed, and my body strength was more (upper body) having been off my feet for two years.

After that I went to public school, I did have a really wonderful art teacher, Julian Levy. He was supportive and an extremely nice man. He would take us to New York once a year, things like that. In high school, around 11th grade, I decided to become a painter. I went to summer art camp and (had) a teacher, a master’s student at Tyler. That was the first time I used oil paint. He saw I was interested in figure painting and advised me to go to the Pennsylvania Academy.

Pete: It’s so wonderful to have those very kind teachers and mentors in your life.

Larry: Yeah. It’s crucial for young folks to have that kind of exposure.

Pete: So then you went to PAFA. Tell me a little bit about that time and then what happened after that.

Larry: I struggled in high school with academic subjects. I did really well in art and I was fourth in the city in gymnastics so I did well in that. I think any experience like that, if you do well in something it helps you with other things. You build confidence, learn about yourself, especially if you get that when you’re younger. Well, any age maybe. I could have gotten a half scholarship for gymnastics at Tyler but I had to retake Spanish. The summer camp instructor advised me about PAFA and I thought ‘oh, I can avoid that if I go to art school.’ I really loved it, even though it seemed strange to me, the different, new people, I think it felt more at home.

Pete: So after PAFA, as you said before, how did you make your way?

Making His Way

Larry: I mostly survived having part-time jobs. It was a struggle. I kept painting as much as I could. I was out of school about three years, living in Germantown. My folks had just moved to Michigan and my Aunt’s house on Yocum Street became available. So I moved back to the street where all my relatives had lived. It was very inexpensive.

Pete: So through the years, you’re continuing to paint and support yourself with part-time jobs.

Larry: About five years out of school I had my first show. No sales. I remember talking to people and they’re asking what are you going to do now? Well, I’m going to keep painting. I had a friend that said you could do your own show. They said if somebody won’t do it for you, you do it yourself. It was really good advice. Many artists (feel) ‘Gee, I can’t get a show at a gallery.’ So you look for a space and you try and put up some stuff. And so I made bunches of these little watercolors. Little street paintings around Queens Village. And just a couple months after the show that failed I had a sale at this person’s house.

Pete: And you sold some paintings?

Larry: Yeah. Right around Christmas time, It wasn’t a lot of money, but I made a little. I’d also pick up commissions and worked part-time jobs. But one summer I decided, no, I’m just going to paint. In 1979 I had a show at the Peale House of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The show was reviewed in the two main Philadelphia newspapers. That really started my professional career.

Pete: And how long after school was that?

Larry: It was about eight years out of school. Then around 1989 I had my first solo show with Gross McCleaf…and have had many since then.

Pete: So now do you have a collector base?

Larry: Well, that’s hard to say. People have collected my work over the years. Some of it’s due to Gross McLeaf, some of it’s due to me.

We talked a bit about the ebb and flow of styles.

Larry: The eighties were a high point in all the art markets, even in Philadelphia. A few big galleries opened. They were doing really well, but they didn’t stay long. The internet and social media changed the whole landscape. I noticed people’s careers would pick up or go down. You’re going along and you don’t realize you’re on a wave. The art market had this big boom of neo-expressionists. There were German and Italian painters that became famous. It came to the United States and all those American neo-expressionists got popular for a while. I thought, oh, people still trust primitives because they’re sincere. They’re not doing it to be on the cutting edge. There’s no way to know how to navigate that sort of thing, except following the lead of the people you admire. You realize that all these really wonderful painters had this incredible struggle. So you have to get going and hope you’re really good and that eventually people recognize that.

Pete: It’s a funny thing. You can look at some artists and you say, yeah, that deserves to be in the Met.

Larry: There’s a lot that goes into that. You’re always making judgments about your work and how to improve it. I know a group of critics that came down from New York for the master’s program at the Academy (PAFA) and I heard this one person categorically tell every student they weren’t doing what they needed to do. I’m thinking, how was that helpful? It was like you have to invent something totally new or you got nothing. Where do you start? Most things grow out of something. There are some people who are truly innovative but they grow out of something that came before. As the fashion part of art circles around it washes out.

Pete: Almost everything that I look at in the New York or international scene seems precisely calculated. If I do this kind of image, in this kind of way, and this kind of scale, with this kind of finish, I can find a big market for this. It’s almost like advertising, hitting a market niche.

Larry: The art world is crazy in what it values most. You have to keep following it and be open. I mean some of my favorite artists don’t do anything like my art. People like Richard Diebenkorn or Joseph Cornell.

Influences and Favorite Painters

Pete: I can definitely see (Diebenkorn in Larry’s work). There’s that sense of light and space.

Larry: I like Bonnard too. It’s a very different kind of painting…a tapestry of color. It has some suggestions of space and scale. I remember seeing a black and white photograph of his studio and they put (Bonnard’s painting of the studio) over it and it was amazingly accurate. But the light inside is as bright as the light outside. The color has changed and a magical transformation happens. This painting (Larry gesturing towards a work-in-progress) still needs some work.

Pete: It has that afternoon light. And in the painting everything talks. This is what I love about Hopper.

Larry: Yeah. Hopper’s great. (He paints) a lot of subjects (similar to) John Sloan, but psychologically they’re really different. I’ve spent a lot of time trying to figure that out. In one Hopper there’s a woman sewing and a window behind her. What is it about this that makes me feel like I’m peering into the room? And when I look at John Sloan, he has people in a window. You’re looking at them, but they know you’re there and you know they’re there.

Pete: It’s like Hopper or Sloan project back and create the perspective of the viewer. That’s really interesting. Wow. I never thought about that.

Larry: It connects on other levels. Vermeer’s painting of the painter in his studio. I saw that painting in person and it has this quality. When I looked at it I kept feeling there was somebody behind me looking at me. It’s compelling and mysterious. Hopper had a way of using structural (devices). There’s something in front of the figure, some barrier that emphasizes that fact that you’re looking over something. There’s a wonderful Hopper where you see two figures through a set of windows. It’s like going by on an elevated train. The woman is playing on a piano and the man is reading the newspaper. They’re separated. The woman has an air of boredom…she’s just tinkling on the piano. You feel you just happen to be glancing into this world at this moment and so it makes you aware of yourself.

Pete: Vermeer seems like a celebration of material, material and light.

Larry: There’s a painting of the sleeping servant. the Dutch painters would make very illustrative paintings. It was a parable on how to behave. And when Vermeer paints this person sleeping it’s not so much a narrative… really just a person sleeping. It’s just reality. That’s why they’re so moving.

Larry has lived in Philadelphia and painted the places he loves for more than forty years. He creates work that captures the melancholy of the afternoon sun; that brings us into moments of peace and communion. He teaches, part-time, at the Barn School in Millville. You can also study landscape painting with Larry at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. His work can be seen and acquired through Gross McCleaf Gallery.

Read more articles by Pete Sparber on Artblog.