“Exhibiting Forgiveness,” a promising film debut by renowned painter Titus Kaphar, deserves endless praise. The act of painting becomes an iconic symbol in this heavyweight narrative. Unlike other fictional pieces about visual artists shown in Angel Kristi Williams’s “Really Love” (2020) or Kathleen Collins’s “Losing Ground” (1982), Kaphar created most of the paintings in the film, making the cinematic experience more personal.

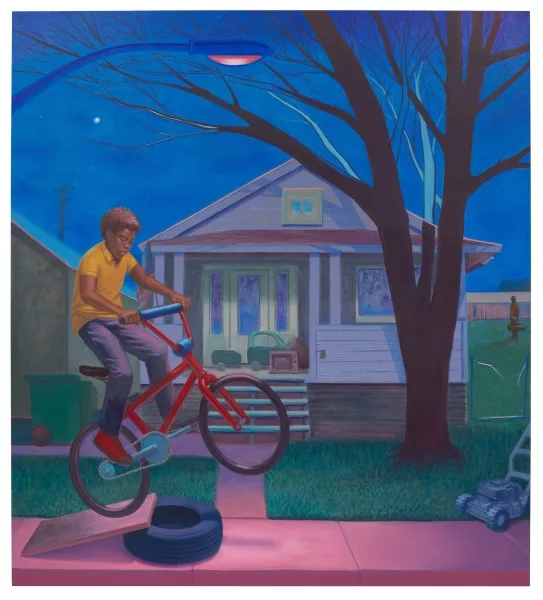

For Tarrell (played by a splendid Andrè Holland), art has the power to break detrimental family cycles. He submerges his inherent psychological demons beneath metaphorical brushstrokes. Between hurt, frustration, or pure leisure, he throws himself into painting, his body a moving, gestural vehicle. He dons a paint splattered denim jumpsuit, armed with his artist tools inside of a large studio connected to his house. As passionate and raw as a sensuous love scene, tender closeups grasp on his active hand color mixing, applying juicy layers to prepped canvases, or wiping out figures altogether. These scenes— enhanced by composer Jherek Bischoff’s jazz-infused soundtrack— showcase how painting is no mere hobby, that the physical activity gives Tarrell an undeniable purpose.

While the painting studio owns Tarrell’s heart and soul, he adores his musician wife Aisha (Andra Day) and his creative son Jermaine (Daniel Michael Barriere), a little boy playing on his miniature piano or drawing crayon pictures. Tarrell, Aisha, and Jermaine symbolize a new, healthy balance— an escape from the damning past that threatens to overtake Tarrell. Yet when Tarrell takes time away from his art to help his mother Joyce (an incredible Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) move into a new space, things go awry. Joyce isn’t interested in leaving the house at all. In fact, she intended to pressure Tarrell into forgiving his recovering addict father La’Ron (great theater actor John Earl Jelks). Tarrell has an internalized dark side that emerges through vicious night terrors or whenever he’s in his father’s presence. This is a reality victims of abuse face when others take the sides of abusers and encourage a positive relationship instilled by religious doctrine. Joyce knows that La’Ron was abusive. She’s seen and endured the damage he’s caused. It doesn’t stop her from loving La’Ron and wanting Tarrell to suffer in that precarious love alongside her.

While Tarrell takes the art route, Joyce and La’Ron have their own escape vessels. Joyce upholds the Bible, continuously allowing her troubled first love back into their lives, misusing religious text as though it wasn’t the very tool that masters repurposed to condition the enslaved. La’Ron’s journey to drugs lulled him away from the everyday struggle— his own cruel father and raising a baby he wasn’t prepared for. On the latest return, La’Ron tries to convince Tarrell that he has been clean for six months and quotes from the Bible too. Tarrell is unreceptive to allowing him access to his life, especially his grandson Jermaine. In between Tarrell and La’Ron’s tumultuous encounters, Tarrell’s imagination conjures his young self pushing large paintings down the street, rich paintings of a past that refuses to leave his mind.

At the basketball court, Tarrell and Joyce watch the old neighborhood teens play. Joyce’s sudden confession of still being in love with La’Ron despite the trauma disgusts Tarrell. Their heated debate becomes so intense that Tarrell leaves behind a tearful Joyce. He is a man who has freed himself, but realizes that he’s powerless to save his oppressed mother. Maybe Joyce feels stabbed by the brutal daggers of Tarrell’s hatred. Perhaps, deep down inside, she longs to be rid of the bonds that tie her to La’Ron. However, it is far too late. She’s in too deep, weighted by history and the ingrained Bible, shackled. Painfully enough, you never see that La’Ron feels the same devotion as Joyce. Moments later, Tarrell cannot shake his desperate love for Joyce. The disappointment in her heart’s choice matters less. A poignant honesty exists in his sudden plight to paint her. Away from his studio and in the sparse motel room he shares with Aisha and Jermaine, Tarrell has no paper, no canvas. He rips the sheet from the bed, attaches it against the door, and gets to work.

Among the many poignant scenes throughout the two-hour picture, a significant moment happens at Tarrell’s crowded gallery opening. It demonstrates the behaviors required of Black visual artists still steeped in an overwhelming white collector’s realm. Tarrell cannot handle the negative feelings that his father’s presence arouses. He lashes out at a patron begging for a selfie and La’Ron during the opening. A shocking reaction reverberates across the entire room, the domino effect having stark consequences. With Tarrell’s rising inner growth comes an unexpected parting gift for La’Ron that will cause anyone’s eyes to well up.

“Exhibiting Forgiveness” is beautiful and profound with an authentic, resonating story, vivid cinematography, and captivating score. Titus Kaphar certainly nods to Barry Jenkins and James Baldwin, unafraid to depict tender Black masculine relationships and revealing that boys and men cry. In addition to providing a stable future for Jermaine, the heavy burdens Tarrell carries are released through the healing properties that painting grants him. Kaphar portrays painting as a gentle and turbulent action and as a gratifying, emotional therapy. The film’s biggest takeaway is that you can try to navigate through embittered memories by using creative methods and forgive the circumstances if willing. Survivors with pasts similar to Tarrell bravely acknowledge that the people who’ve caused you harm do not have a right to remain in your life.

“Exhibiting Forgiveness” is available to rent on Plex, Apple TV, and Fandango at Home.

Read more Janyce Denise Glaspers reviews and features on Artblog.