“Breakdown repair,

breakdown repair,

!@#%^&*@$@#

Whoops, I have to treat it like my loving

relationship with my cats.

“How are you feeling today, my purring machine?””

-John Doe Co.

Out-of-Order Technology, 1975

I’ve visited and revisited the show Nature Never Loses at the ICA, a survey of sixty years of Carl Cheng’s work. A resounding takeaway for me is the insistence on impermanence, erosion, and change. Humanity can be so obsessed with immortality, constantly looking for ways to create permanent projects, maintain them, and ensure their intransience. After my second viewing of the show and reading the materials, I listened to the interview between Carl Cheng and the exhibit’s curator Alex Klein, Head Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs, The Contemporary Austin and formerly a Curator at the ICA . They discussed “John Doe Co.”, his one person company, invented it to better acquire industrial materials, and to more easily file his taxes. This gesture also serves as a powerful allegory for the disidentification of capitalism. At the time John Doe Co. was set up during the war in Vietnam, soldiers’ bodies who were not able to be identified were returned to the country without a name and were referred to as “John Doe.”

Cheng could not be recognized by the Internal Revenue Service without diffusing his identity through the armature of a company. During the war, Cheng wondered, were he or one of his five brothers to be sent to war in Vietnam – as first-generation children of Chinese immigrants – would they be perceived as Americans or as an enemy? In the interview, Cheng stated that there wasn’t a plan about how the work should be maintained, that when he would die, so would his company.

His practice exists in many materials – calcified avocados, repurposed circuit board, venus flytraps, and sand…a large portion of his work is tools, mechanical tools that require Cheng to operate them, “My art tools are not a performance. It’s a hammer. It’s a drill.” (from the exhibition literature). The desire to preserve the brilliant work exactly how it is is understandable but perhaps impossible. We may have the tools but not the work itself. This is a logical progression from a career made on the outside edge of the commercial art world, choosing engagement, erosion, and exploration, rather than market, legacy, or permanence.

Storage is a huge problem for artists and for all of us on Earth. Where do we store our work? Where do we store our waste? Our cars? Ourselves? And in what conditions? Cheng stored supplies, artwork, and compost on the roof of his studio unprotected from the California sun.

He discovered he could use the processes of erosion, weathering, and decay. Leaving out avocado and orange peels, and playing with them intermittently, he said “No matter what I did to it, something would come out of it.” Cheng and the viewer are now both able to observe the decay and feel this true curiosity.

Cheng is known for his itinerant studios. My friend will owen, who gave me a tour of the show, assured me that it’s likely that the artist is tinkering and making work on little table top studios everywhere he travels, even while he was in Philadelphia installing the show. Cheng speaks about his travels around the world in the 1970s with his partner, Felice Mataré, “American culture wasn’t enough.” He wanted to know where art could be and who it was for. Cheng realized that he was interested in the idea of artists based in small communities making beauty and finding poetry with what was around them. These true artists, who while recognized and respected by their community, were not known in the art world.

Like a kind of tinkerer in the town square, Cheng’s practice at many times is outward facing, including participation as a way to further his research, asking questions with the viewers.

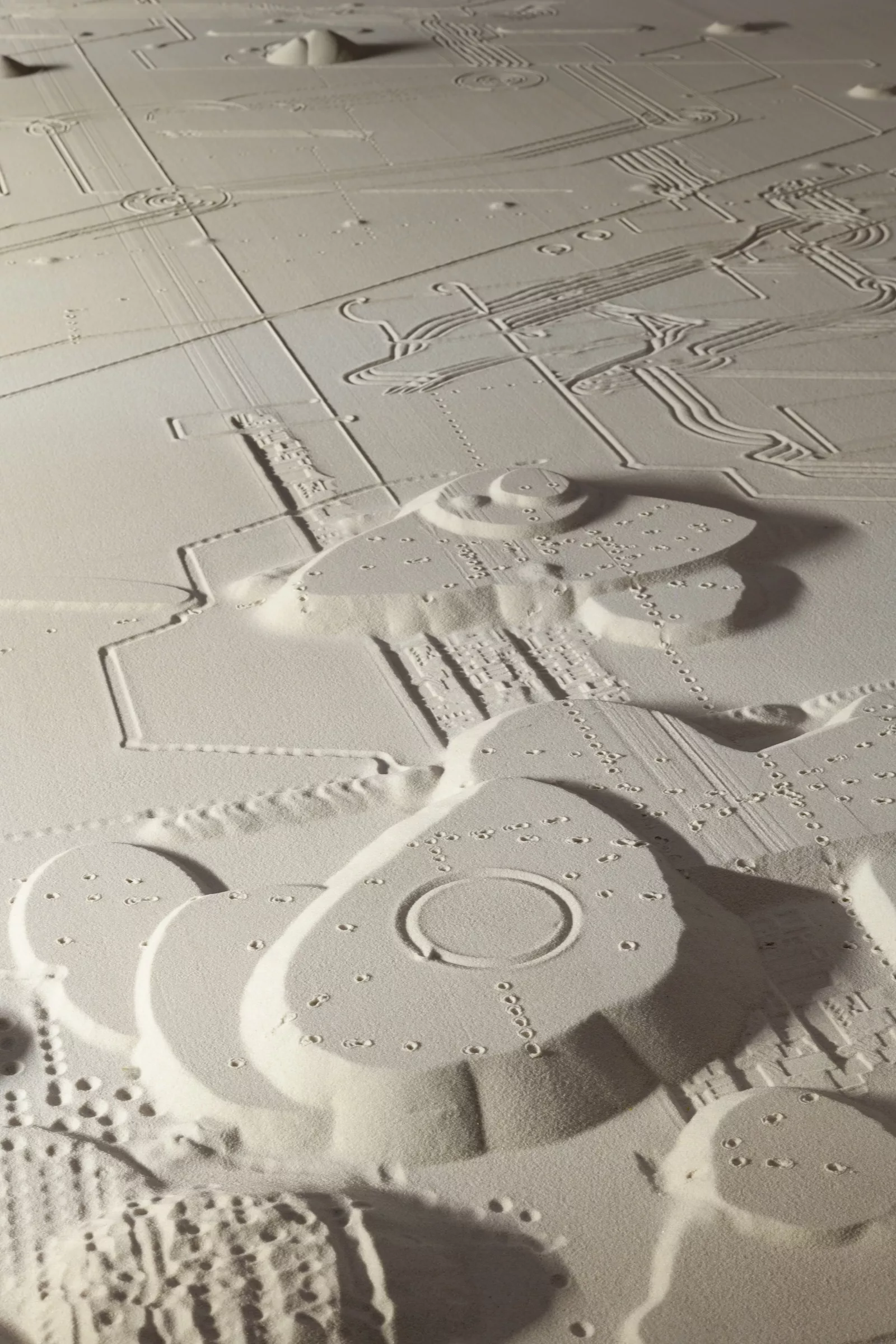

A stunning piece on the second floor of the show is one of the Human Landscape series “Imaginary Landscape 1” (2025), the current iteration of a practice of making drawings with sand, an impermanent craft with an ancient lineage. The series began in 1966, with a prototype of his sand rake tool, which dragged lines across the sand. In 1978 he mounted “The Natural Museum of Modern Art” in a condemned building on the Santa Monica Pier. Viewers would peer through the windows and by putting 25 cents in a slot, could select a UA (Unspecified Artifact) which would make a mechanical drawing in the sand. The artist says it wasn’t about the quarter but about the viewer “buying in” and wanting to see something. This grew into incredibly large proportions when, from 1983-1988, the “Santa Monica Art Tool” was active. The tool was used to create “Walk on L.A.” The tool, a gigantic round cast concrete roller , that when pulled by a tractor on the beach made a 2-inch relief of a miniature city on the sand. This practice invites entry into an intangible place of universal childlike play – building towers to knock them down, dragging sticks through the sand, and watching for the water to come to wash it all away. An urban and suburban sprawl illustrated in relief with buildings, streets, cars (including traffic and pile-ups), which had the potential for viewers to stomp on it, also enabled them to reflect on the precarity of the built environment.

One of my favorite inventions of his is the term “human rock.” If a machine breaks, it has no function anymore. It would get collected by a trash receptacle, perhaps compacted and buried in a landfill. It would become a sedimented thing, a rock made by a human. Cheng collects these curiosities, setting them in his “erosion machines,” endless systems where water is poured onto human rocks. In another compartment in the machine, a wire shelf is helpfully loaded up with more human rocks to erode, even though the currently eroding one may take anywhere between 10 minutes and 10,000 years to become eroded.

Nothing in technology survives. Cheng maintains that because human thinking is a natural process, upgrading and maintaining technology is in itself a natural process. I see this thinking outside of the polarity of human vs. nature, and nature vs. technology. Cheng instead presents these categories as poetically interwoven, approaching them within the materials of his work with the curiosity of mutual exploration and sustainment. Rather than reject human invention in favor of a more ‘natural process’ – Cheng uses processes such as weathering, erosion, and sun-drying, as well as mechanical, technical, and electronic processes. Continual change and adaptation based on changing technology, as well as environmental factors, challenge ideas of permanence, finality, and end product.

This work is full of poetry and humor. While critical of war, capitalism, urban expansion, pollution, and more, there is something more engaging, more interesting, more open, and complex than critique going on. The message is kindly pointed to quite simply in the exhibition title, Nature Never Loses, which was taken from a kind of repeated expression Cheng uses. The world we humans have built for ourselves is precariously balanced in time, our buildings will fall down, our waste will become sediment, everything will erode. It’s not a competition between humanity and nature because, in time, nature always wins.

Carl Cheng, “Human Landscapes – Imaginary Landscape 1” (detail), 2025, sand. All images are courtesy of the ICA.

Rather than do what many artists and writers have done – extrapolate a future based on their present, which, dependent on their tuning, interests, and goals, can skew wildly in terms of describing our present – Cheng is involved in deep looking into that present moment when the work is receiving his attention. “I don’t feel like I’m predicting the future, I’m living in our present and I’m documenting what we’re doing and it comes from a more natural attitude than conceptually trying to push, so if it reveals itself to be very present it’s because that’s what it is. I didn’t try to do it – it’s what I did. I’m not driving towards something I’m trying to experience more completely what we’re doing today.”

Remaining present is very challenging, and at times can feel impossible. Right now, where it’s difficult to be, it seems that jumping into an easier or more comfortable future or remembering an easier or more comfortable past is the most logical thing to do. The present defies logic. Grief constantly pulls us backwards and fear drags us ahead. We all have no choice but to be in the present, yet it takes a certain strength to wade in the tide of time and remain still and observant. We are very lucky to be able to see this work by Carl Cheng, which is made in that effort. Like everything, Cheng’s work will break and break down. The sand drawings will be swept, the rocks erode, the tools will fall into disuse and disrepair. Cheng has given us a beautiful map of presence, if we trace the drips and drags through the sand drawing with our eyes, we can work to stay in now. Now is where we have the tools to work.

NOTES

Carl Cheng is quoted from the ICA’s exhibition materials, from a video in the exhibition, or from his interview with the curator Alex Klein held at the ICA in support of the exhibit. All images are courtesy of the ICA.

Carl Cheng: Nature Never Loses, ICA Philadelphia, through April 6, 2025.

Read more reviews and articles by Lane Speidel on Artblog.