Nearly three years ago, I encountered abstract expressionist painter Vivian Browne’s work for the first time, at Ryan Lee Gallery in New York City, and two years later at the gallery’s Art Basel Miami booth. This year, the artist’s premiere retrospective, Vivian Browne: My Kind of Protest, at the Contemporary Art Center located in downtown Cincinnati, fulfilled a desire to see the artist’s tremendous range. Curated by Amara Antilla and Adrienne L. Childs, Ph.D, the well-organized and well-archived exhibition reveals Browne’s varied mediums: painting in oils and acrylics, experimenting on canvas and silk, and mastering photography and printmaking techniques such as etching and woodcut.

The large exhibition is split into four sections: early figuration, landscape and ecologies, abstraction and internationalism, and the Little Men series. Behind glass, archival material shows the reach of her art – in pamphlets with her art on the covers, in sketchbook pages of figurative pastel drawings, and a New Art Examiner newspaper clipping highlighting her role in activism. Black American Literature Forum, a 1973-1991 quarterly magazine published by St. Louis’s African American Review, had a spring 1985 issue featuring Browne surrounded by nine other artists. A small TV plays Browne’s episode from “Black Artists in America,” a 1975 documentary interview series which also has segments on Faith Ringgold, Betty Blayton, and others. A bespectacled figure with an afro rivaling Angela Davis’s, Browne said of her Little Men series, “It has come to my attention that men really rule this country. In any case, they have the power… that has been shown in the art world as well.”

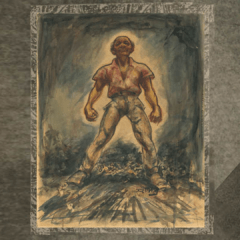

While Browne (1929-1993) protects the women in her life and uplifts the nature that inspires her, she punches hard in Little Men. For example, the large scale “Seven Deadly Sins” is a riveting masterpiece evoking grotesque nightmares regarding white male privilege. Eight blurred, ghastly heads— attached to wide, bulging bodies or floating in the strange unknown— are painted in dreary tones of pink, gray, and yellow. Activated hands either wave frantically or clutch bottles to their fists or lips. Their twisted bodies act out various states of distress, caught between screaming or drinking away their anxieties. These half human, half monstrous entities symbolize the fact that they can do the absolute worst yet still be coddled and respected. Browne shoves aside the frustration of trying to survive a man-controlled climate by emerging into surrealist territory, an artistic era lauded for transferring eccentric fantasies into sophisticated allegories. What better way to document the detrimental circumstances of her time? A time that bleeds into our own current reality? The raw, desperate energy of her rage blazes through every piece displayed.

Browne’s figurative paintings employ the sharp lines and bold shapes that predate her full-blown transfer into nonrepresentational work. Along the line is “Mother,” a portrait of her mother Odessa Browne, “Camille Billops” (1933-2019), friend and fellow artist, and “Vivian (Self-portrait).”

“Mother” is a tender, attentively rendered pastel palette painting. Keen interest lies in capturing light and the serene expression, the figure’s body on the verge of dissolving into space. Her low collared, simple dress and neatly pulled back hair hints at the woman’s modesty. “Camille Billops” explores saturated hues and black outlines, the figure’s face having mask-like qualities whilst seated around zig zag areas that mimic her. She’s wearing a bright red jacket and blue jeans, her hair wrapped in a patterned headscarf. “Vivian (Self-portrait)” demonstrates holding onto academic tradition and the rebellious instincts of incorporating personal style. She looks directly at the viewer, draped in a pink robe, her straight bobbed hair framing her confident face. A wide bowl sits on a pedestal and a painting of a curvaceous woman’s torso hangs among other pictures in the background. This piece within a piece reoccurring in her work.

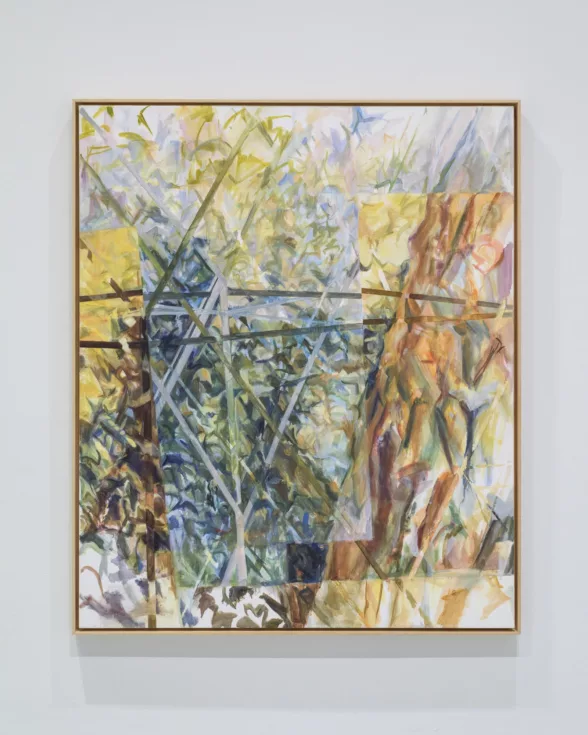

The abstract section emphasizes the pivotal role of nature. The maquettes and sketches retain an artist’s desire to document the multifaceted world around her, especially her time spent in California where she kept a studio. “San Joaquin/Diaresis,” an earthy toned piece painted a year before she died of cancer, places geometric patterns on top of each other. This composition within composition involves intentional breaks between unified rectangles. Thin, diagonal lines almost interact, but lose contact by less than an inch. The midsection colors vary and are painted heavier than the surrounding lighter edges. The word “diaresis” has two meanings: “two dots placed over a vowel to indicate a specific pronunciation” or “a natural rhythmic break in a line of verse where the end of a metrical foot coincides with the end of a word.” Perhaps in this evocative work, Browne reveals her complicated duality in California, finding a certain peace in creating yet also knowing that her tomorrows became unpredictable.

As we endure a new age of censorship and gatekeeping, My Kind of Protest presents an undeniable timeliness that combines political peril with artistic freedom and courage. Vivian Browne wasn’t afraid to showcase life’s infinite beauties or broadcast societal ugliness, marrying her creativity and advocacy, aligning herself to others who shared the same beliefs. Artists and writers have a heavy responsibility to tell the truth during this tumultuous period of spreading lies and growing civil unrest. Even as exhibitions by artists of color and LGBTQIA communities face unlawful cancellations across the country, we have to keep showing up and discussing curations in the vein of Browne’s. This exhibition centers an artist who deserves to be seen. She was an artist, a professor, a world traveler, and an activist staunchly committed to fighting against the patriarchal structures that are still operating in our history today.

Vivian Browne: My Kind of Protest runs until May 25, 2025, at the Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati, OH, before traveling to the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C., from June 28 – September 28, 2025.

Read more reviews and articles by Janyce Denise Glasper on Artblog.