If the phrase “indie sleaze” means nothing to you and the name “Santigold” doesn’t ring a single bell, then you probably won’t feel like you’ve been struck by lightning when viewing Melissa Simpson’s solo exhibition, SATIN. On view at Tiger Strikes Asteroid PHL, the photography exhibit from Philly’s own Melissa Simpson celebrates indie sleaze, a fashion and music scene that ran wild in Manhattan at the turn of the century. Like many other teens who were too young and too far away, Simpson was not part of the indie sleaze scene directly, but she was able to find avenues towards it through trendy magazines and her own embodiment as an alternative young adult in Philadelphia.

In SATIN, Simpson delves into the blurry boundary between presence and absence. She presents a throughline that connects her own dubious sense of belonging to the visibility of Black woman within the indie sleaze scene, to, in her words, “the social collateral of the still image.” As a photographer, Simpson taps into the medium’s unique potential for both journalism and speculation. She messes with the line between archive and fiction. Sometimes both are needed to capture reality.

Four portrait series make up SATIN: “Afro-Jamaican Apparel”, “Day In the Life Of An It Girl”, “Food, Fabric, Freedom” and “After The Party”. The most sensational images come from “After the Party”. In these photos, Amani Starks, a Philly-based artist and musician, is decked out in myriad fashion trends of the aughts: blown-out tulle dress, thick black eyeliner, reams of studded bracelets necklaces and, quintessentially, a cigarette. Stark’s body is deflated with post-party exhaustion, but she stares cooly into the camera — her confidence invites starry admiration. From the costuming, to the staging, to the inclusion of a green Sidekick phone (also on display in the gallery), Simpson has meticulously crafted a series of images that could have been taken twenty years ago.

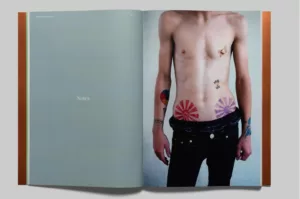

In “Afro-Jamaican Apparel”, Simpson references the infamous, but pervasive, iconography of American Apparel ads. In this series however, Simpson is not interested in recreation. The clothing brand’s exploitive and stark aesthetics are left behind and replaced by images that are gentle, diffused, and playful. Listless poses are delivered by rapper and 2nd generation Jamaican, Shauna Moon, who maintains a gentle countenance as she twirls around a sheet of sheer fabric in one image and completes a full split in another. Simpson has zoomed out to show more than Moon’s thigh high socks, more than her legs and body. She captures Moon herself. The series is a joyful alternative to how clothing, bodies and heritage are captured on camera and sold to the public.

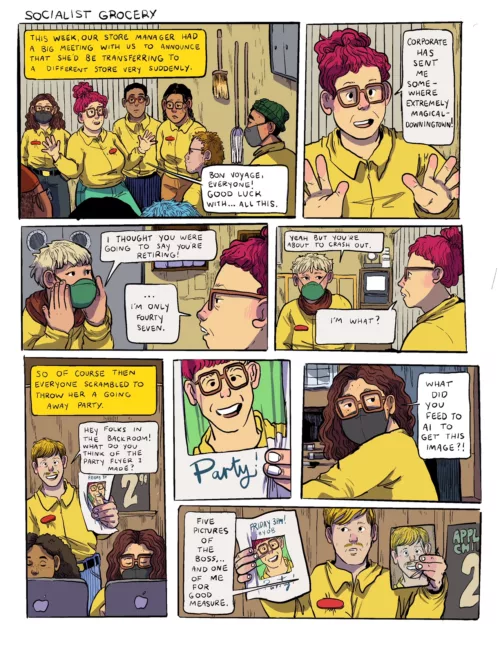

In addition to her photographs, Simpson has brought a collection of archival materials into the gallery space. The showcased items range from CDs to vinyls, to magazines and personal accessories. For those who are in the know, they punctuate the space with delightful familiarity; I ask you, what other art show in the world features both a Bonde do Rolê CD and a copy of two.one.five magazine? A well-worn American Apparel tote bag, the kind with various cities of the world listed in blocky print, is on display as both an archival item and as an activated token within the photo series, “Day In The Life Of An It Girl”. In this series, Simpson has once again found a Philly-based artist who can embody a fashionable archetype. Makiah Stephens is the eponymous “It Girl,” posed with the aforementioned tote bag in a record shop and outside of a bar. Stephens is stylized from head to toe and Simpson uses the quotidian locations to drive home the tension of unattainable chicness.

There are only two prints from “Day In The Life Of An It Girl” on display in the gallery. More photos can be found in the magazine that accompanies the exhibition. Available for purchase, the magazine, titled “Satin”, a play on “Nylon” magazine, contains writings from Simpson, John Morrison and KURO, as well as additional images from each of the photo series. The small publication is a unique inclusion for a gallery exhibition and in line with the overall production of the show; SATIN was promoted through posters and fliers shared around the city and had John Morrison spinning alternative jams during the opening reception. SATIN is its own scene.

The promotional poster for the exhibition is a collage of faces and items thematically relevant to the show. Stephens and Starks make an appearance, as does a vinyl record and a can of PBR. Notably, a keffiyeh is also front and center. In fact, when entering the gallery space, the very first item on display is a keffiyeh placed on a pedestal that has been covered with black fabric. Next to the pedestal is a book of portrait photographs, images that were taken at various parties during the indie sleaze era. A number of pages are marked with tabs and upon studious inspection, it becomes clear that these pages contain pictures of people who are wearing a keffiyeh. Some may have done so for political reasons, but others wore it simply because it was fashionably to do so.

In the “Satin” magazine, Simpson writes about the keffiyeh and how for many Americans the scarf has moved from being a hollow accessory to representing anti-colonial politics. She observes that in 2024 during the protests against the arena in Chinatown, “people of varying ethnicities donned a keffiyeh, advocating and protesting on behalf of a subjugated community. That garment once again represented counteraction to brutality, violence, and marginalization.”

The final photo series in the exhibition, “Food, Fabric, Freedom” investigates the aesthetics associated with global anti-colonialism. For this series, Simpson has placed artist and musician Rachel K. Godfrey in front of four flags from nations facing acute oppression: Palestine, Haiti, Congo and Sudan. Before Godfrey, food from each country is staged in a delicious arrangement. Godfrey wears a calm expression as she stares into the camera, keffiyeh draped around her neck and across her shoulder. The flags that are within the photos are also draped along the back wall of the gallery, reinforcing their presence in the show.

Photographs are mirrors. Their power, or impotence, comes from whoever is viewing the image. SATIN celebrates the joy that portraits can bring but questions if the hunt for social capital disrupts our ability to imagine other possibilities of the world. If social media makes this conundrum even more profound, photography exhibitions, such as SATIN, are more crucial now than ever.

Melissa Simpson: SATIN, Tiger Strikes Asteriod Philadelphia, through Saturday, April 5, 2025.