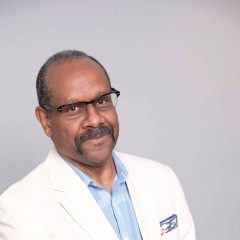

The only thing dull about The Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection at the National Gallery of Art: Selected Works (NGA) through May 2, 2010 is the exhibition title. I’d rather call it, with apologies to Wallace Stevens, Ten Ways of Looking at a Painting, with further apologies for the handful of drawings, prints and 3-dimensional works; it is overwhelmingly a paintings exhibition. The works, some already donated, the remainder promised to the NGA, are superb and the curatorial decisions intelligent, provocative and subtle. Harry Cooper, curator of modern and contemporary art, arranged ten sections, each labeled with a subject to ponder while looking at the art. Then he modestly withdrew, allowing the works to speak directly to viewers and to each other.

The artists, of various post WWII approaches, are mostly very well known: de Kooning, Kline, Rothko, Johns, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, Stella, Kelly and Marden among them. What Cooper’s exhibition did was shake up my usual and customary thoughts about these long-familiar artists and asked me to look anew. I left with understandings that were less neat and contained but a lot more interesting.

The first gallery, labeled Scrape, is an essay in the brushless application of paint. On entering I saw the splendid de Kooning Untitled VI (1983, above), made when the artist’s painting was all gesture and no mind – but what gestures! I peered closely at an untitled painting by Julian Lethbridge of 1989 whose surface resembled alligator skin but couldn’t fathom the paint application from mere looking, despite clear indications of the use of a broad palette knife. Beside it was one of Albers’ homages to the square which reminded me of his description of his practice: no skylight, no studio, no palette, no easel, no brushes, no medium, no canvas. I was caught off guard when Brice Marden’s Picasso’s Skull (1989-90) employed scraping not for the figural lines, but for the background.

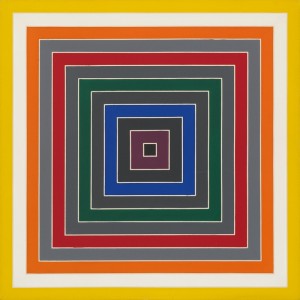

Concentricity was the theme of the second gallery and the surprise here was that it applied to shapes beyond circles. After a moment the themes began to echo, as they would more and more throughout the exhibition. I remembered Johns’ concentric circles in two lithographs in Scrape then saw indications here in Johns’ encaustic, Mirror’s Edge 2 (1993), that he scraped paint through a screen, using it as a stencil. Another Albers in Concentricity was isomorphic to the one in Scrape, with equally scraped paint .

I laughed when I saw the Bochner drawing First Fulcrum (1975) in Line, as the only lines were the negative spaces between the two geometric figures. The lines in Agnes Martin’s Field #21 (1963) contributed to a regular grid wherein each individual line became lost. In Rauschenberg’s Frigate (Jammer) (1975, above) the irregular line was a piece of wire which impaled a cardboard tube at the top, projecting through it and supporting a plastic water glass, while its tail end was draped with a ragged red flag of the sort used by trucks carrying oversized loads.

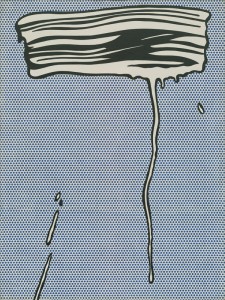

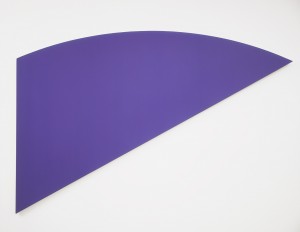

Ellsworth Kelly’s Blue Violet Curve I (1982, above) was the first work visible in Gesture, its gesture created by the curved meeting the straight side of the shaped canvas, turning it into a directional arrow. A more conventional example of gesture was Franz Kline’s Turbin (1959) where the gestural brushwork was as much a masculine display as a peacock’s tail. Another Johns encaustic appeared in Drip, creating further echos; it bore another sign of a screen, this time used to transfer paint, as a stamp. Grace Hartigan is not usually associated with fluid paint, but in Josephine (1983, below), the empress, her contours seeping away, walks through an atmosphere of drips.

And so on, through Stripe to Zip, Figure or Ground, Monochrome and Picture the Frame, with surprises throughout. Exhibitions drawn from the permanent collections are appropriate to the current financial climate, but more than that, when a museum has such great collections they integrate the museum’s collecting function with its public and educational ones, leveraging the returns.

The Darker Side of Light; Arts of Privacy, 1850-1900

The NGA currently has several other exhibitions drawn largely from its own collections. The print department is showing The Darker Side of Light; Arts of Privacy, 1850-1900 through January 18, 2010 then traveling to Chicago, curated by Peter Parshall. I love prints and would heartily recommend this to anyone similarly inclined. It gathers 120 works made in France, Belgium and Germany in the later 19th century, largely etchings and other prints but including a number of small sculptures, reliefs and medals. The premise is that this was the period when the modern notion of privacy developed and with it came a range of art intended to be viewed within that personal space. It was also the period of the etching revival, when artists rediscovered Rembrandt’s printmaking and turned out masses of prints for collectors obsessive enough to be interested in multiple states (as many as ten, all duly indicated on the prints and in catalogs).

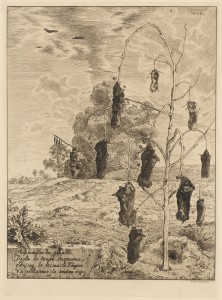

The exhibition is arranged around themes (The City, Nature, Obsession, Violence and so forth), and reveals some of the odder interests of the period that were too marginal to feature in paintings: the dead rodents of Felix Bracquemond’s ‘The Moles’ (1854, above, PETA wouldn’t like it), the plague of Cholera in Paris (1865) by François Nicolas Chifflart, depicted as a swarm of nude figures floating above the city, or the hallucination of fish floating through the sky in Charles Meryon’s otherwise topographic Ministry of the Marine, Paris (1865). Anyone who doesn’t know Max Klinger’s series, A Glove (1880-81, below), has missed one of the late 19th century’s great expressions of fetishism, made at the time the term was adopted in psychology.

One problem with the exhibition is that in a gallery with prints by Degas and Munch it’s impossible to concentrate on the Besnards and Zorns. The exhibition includes a handful of really first-rate artists who overwhelm the larger group who were splendid technicians, but artists of limited, if interesting, scope. It also strikes me as unlikely that anyone who collected most of the etchings in the exhibition would be interested in the one lithograph by Munch, which would bear display at more than hand-held distance.

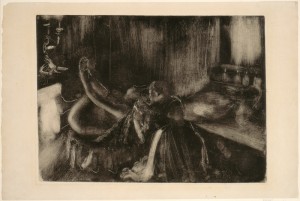

Klinger’s eroticism was displaced or expressed relatively chastely and while the subject runs through several of the exhibition’s themes, its most overt expression is Franz von Stuck’s Sensuality (c. 1891), depicting a nude woman with a huge snake writhing between her legs and around her shoulders. This brings up a significant omission in the exhibition, which is the frankly erotic (Felicien Rops’ genre better-known than those in the exhibition); they were clearly an art of privacy, referred to in the catalog but not on view. This is an occasion when they might reach the museum walls; I assume some linger in closely guarded museum Solander cases.

The Drawings department also has an exhibition drawn from the collections: Renaissance to Revolution: French Drawings from the National Gallery of Art, 1500 – 1800. I can’t do it justice here.