A mix of some great art and lots of good will make up the exhibit Shelter at the Painted Bride. The exhibit asks the question, What really matters to sustain us as human beings? While not literally answering that question, a number of answers are on display here, and it is those compelling, individual answers that make this show tick.

The back story is that curator Marianne Bernstein matched up 17 artists with 10 families who had had their homes restored by volunteers of Rebuilding Together Philadelphia. The artists waded into the personal lives of the families, visiting, talking, sharing, and in some cases volunteering to make additional repairs.

Some of these match-ups worked brilliantly. The personal outpouring in some cases fuels something magical. But some of the exhibit is a straightforward record of people’s lives–personal and wonderful because people are wonderful. And some of the exhibit is just artists doing their thing, inspired by what they saw but strangely cool in the highly emotional environment of the show.

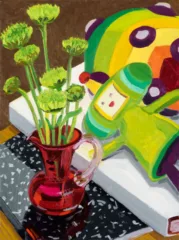

Artist Matt Savitsky’s relationship with Joel and Panina Brown, an intense North Philadelphia couple, was a combustion chamber out of which came a collaboration between Savitsky and each of the Browns. Joel, who has some engineering experience from the military, is an inventor of solutions to the world’s problems. He’s also an artist, although he doesn’t think of himself as one. And Panina loves–and buys to sell–inexpensive catalog products, the sorts of tschotschkes that no one needs. It is not clear how much she sells. But we know she buys and buys. Matt made a real-world version of a bed with closet and storage that Joel had designed for college dormitories. But in Matt’s version, the storage cubbies are stocked with Panina’s merchandise, priced so low that people were buying.

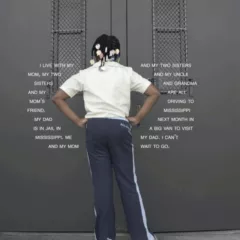

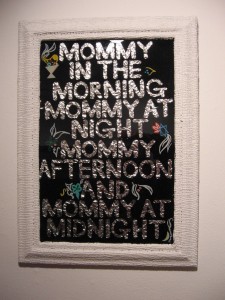

Savitsky also made a tin-foil “drawing” of the words to a song Panina made up to put her children to sleep. When I visited Shelter, Joel and Panina showed up, and she sang me the song, which sounded like a jump rope counting rhyme. Savitsky’s art shows the mind’s and hand’s ability to create something from nothing. Both of these deadpan pieces reflect the Browns with sympathy and understanding, at the same time giving the couple and their fantasies a voice and reach beyond what they themselves are able to achieve. Not on the wall of the show but included in David Kessler’s video of this couple is a watercolor drawing by Savitsky that visualizes another of Joel’s ideas–a home made up of glass-domed pods for each family member.

Kessler’s video is one of three spectacular videos that capture their subjects. Kessler’s rises above documentary with his sharp eye for telling details. He shows the Browns’ passions as expressed through physical objects and their words. The video, which doesn’t show the couple’s faces, does show how their minds and personalities create the lives they lead and the values they have.

Ricardo Rivera’s video is of the bedside vigil of Albert Harrison as his partner Gloria Brown recounts non-stop her memories as she lays dying. The video is projected a hospital bed and the wall above to put the viewer in the room with them. While the projection doesn’t quite do that, it does pack a punch, with the urgent talking of Gloria and the facial expressions of Harrison as touchstones of life and love and the importance of shared memories. A Zoe Strauss photo of Albert shortly after Brown’s funeral also packs a punch, especially if you know that is what you are looking out. Without that bit of information, I was a bit confused about its edgy oddness.

Also notable in video is Danielle Lessovitz’s portrait of Juanita Wooten, who delivers her philosophy of life as she gardens her collection of cactus. Wooten wonders about survival and the feistiness of nature, both issues reflected in her own character. Mostly wheelchair bound although she gets around a bit on crutches, Wooten has an indomitable spirit. She had trained as a textile designer, and her love of visual beauty is reflected in her appearance. This video was inspirational. But nearly all the video had inspirational moments.

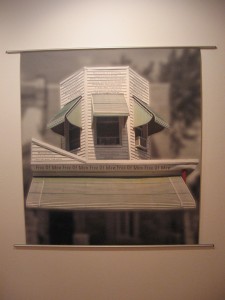

Other works that accomplish the mix of understanding and sharing come from Judy Gelles, Katie Tachman and Marc Bernstein. Gelles’ portrait of JB’s house and words recounts the West Philadelphia woman’s take on life, which she prefers without men. The wry but sympathetic capture of so much with such economic means is remarkable. Tachman’s photo-based wallpaper, which includes portraits of Zettie Brown’s mother and Tachman’s grandmother, captures a sense of home and the connections between people, love and keepsakes. Marc Bernstein’s vision of Robert Small’s loving family home is strangely wonderful, with its windowed curtain facade and its cat birthday party.

Some of the other works in this show succeed in other ways. Phillip Adams’ piece, a spectacular ticker tape parade, communicates an ironic anger and sadness, and Daniel Heyman’s prints get at the value and dignity of an individual. Both of these artists were connected to a group of veterans, and the works spotlight the indifference of the military to the men whose lives it chews up. These pieces, without their sense of family, seem like they belong to a different show.

I didn’t see Damon Reaves’ performance, only a related box of dirt, but it is scheduled to be repeated on First Friday, Dec. 4. Others in the show are Adam Corrigan, Joan Wadleigh Curran, John Broderick Heron, Dierdra Krieger, Nicholas Santore, and Eva Wylie.

When I saw it, this exhibit needed a road map. The exhibit essay by Bernstein was intended to do that job, but that meant picking it up and reading it then and there. I do know Bernstein added some more directional signals after I was there. I hope that did the trick, because the show had so much to like.