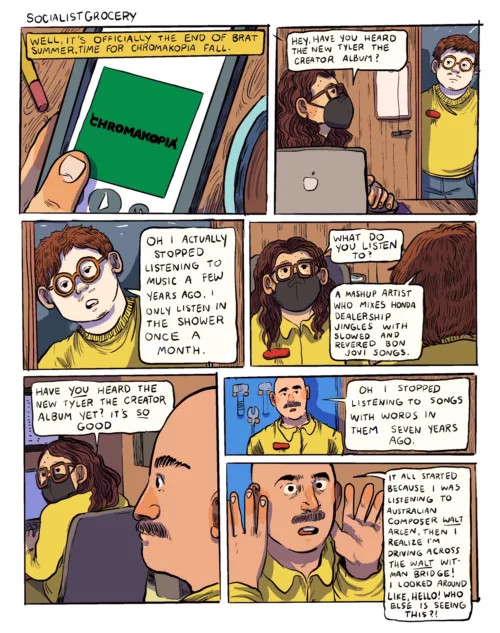

For more than thirty years Ida Applebroog’s work has given us an unblinking view through the windows of America at home. Rejecting the bawdlerized domesticity of television, she has taken us behind the stage sets to reveal the disturbing unease, mis-communication, power struggles and violence of our private lives and their inevitable connections to events in the larger world.

With Monalisa at (Hauser and Wirth, New York through March 6) Applebroog offers us a view of her own interior space; we’re not allowed in, but we can look through the windows and cracks. She has taken a series of drawings made forty years ago and put aside, and in translating them through her current practice has built her own glass house, clad in their translucency.

A large painting of a figure with the unclothed body of a young girl and the made-up face of a woman stares at us from a position opposite the door. It is clearly her space. Through the door itself we see through the large head of a strange figure – with whitened face, sooty eyes and reddened mouth, he/she looks like a clown with unfinished makeup and hair pulled back to receive a wig. The intense eyes might be the girl/woman many decades into the future. The house they inhabit is papered with inward-facing drawings, all of them close-up images of a woman’s open crotch. The staring girl with bare pubis is surrounded by attributes of the woman she will become; the idea is mysterious and scare-y.

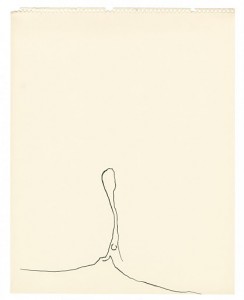

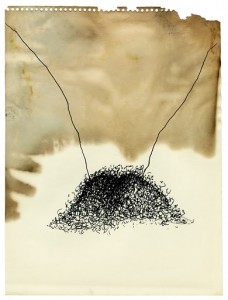

The original drawings were done when the only physical privacy available to Applebroog — as wife and mother of four – was in the bath; so she took her pens, pencils and paper and, looking in the mirror, drew her most private parts. Over and over and over, during several weeks in 1969, she drew her vulva, affirming that she was an artist, and a woman. A woman, an artist. She produced more than 160 drawings; in some she explores ways of looking, in others it is clearly the act of drawing that concerns her. Her being a woman and being an artist were inseparable.

When the drawings reappeared from deep storage in her studio, Applebroog translated them onto Gampi paper via computer, adjusting the hue then adding pale washes of watercolor. Scratchy lines became softened, like charcoal or pastels. A selection of the original drawings is installed in the gallery’s second floor. They are beautiful and moving. Some record each curl of pubic hair, others are so spare that the labial folds appear almost abstract. These are more than an artist taking advantage of the self as most available model. They record a woman looking at herself at just the historical moment when that idea was becoming public and politicized. Women got together to examine themselves; they held masturbation workshops. The personal is political was the mantra.

Forty years on, explicit imagery of women’s sex in art galleries is still unusual; Applebroog’s see-through house gives us all reason to re-think women and our bodies in both private and public realms.

A catalog accompanying the exhibition, Ida Applebroog Monalisa (ISBN 978-3-9523630-0-3) has extensive, color illustrations of the installation, some of the re-worked drawings and a number of the original drawings. In an essay Our Bodies, Our Houses, Our Ruptures, Ourselves Juliet Bryan-Wilson places Monalisa within Applebroog’s work, women’s depictions of house imagery, the gendering of housework and feminism’s multiple discourses of the female body. She discusses female genital imagery in women’s art (although she mis-attributes Valie Export’s Action Pants: Genital Panic to Gena Pane), and ends with a self-reflective note about a body of work that began with looking in the mirror.