As luck would have it I went to see the work of a young French artist named Alba Pistolesi.

Alba is , in her words, obsessed with cancelling the usefulness of objects as well as with table legs and their standard 72cm length. A week earlier she had shown me a large wooden die and a faggot of table legs that were meant to be screwed into the die on each face. The number of legs per face were to correspond to the number on the face of the die.

This results in an object that evokes either a virus or a creature from the Burgess shale.

Luck is a fundamental component of every human enterprise. Behind every action a pair of dice is rolling. Machiavelli insisted that the Prince be aware that he was Prince mostly by luck. His job was to never admit it. Many artist have employed luck and randomness in their work. Here, Pistolesi has cancelled luck. First, one of the dice is missing. Where is it? Is it in use? Second, this die cannot be rolled. Its uselessness stops time, stops gaming, and reaffirms the non utilitarian nature of art. In this process “I-de” becomes art because it cannot function, even though the utility of the table legs remain whole. This die can stand on sides 4, 5 and 6. Standing on sides 1, 2 and 3 it will fall over unless supported by a wall. However, “I-de” invokes walls and/or flooring at the point of each table leg. It is easy to imagine it enclosed in an unmarked box like Schroedinger’s cat. We would always be uncertain of its position. Heaven forbid we should mark the box like a die and roll it. What would be the true roll? The internal or external result? Forget it. By the time you’ve boxed it it would be too big to roll anyway.

Where do people like to throw the dice? In games. Backgammon, for example, presents the sublime opportunity to make the most of a roll. In board games winning and losing are clearly defined and the game time is finite. Not so in art, if we consider it as a game. We can spend a lifetime rolling and never know what we rolled or if we have won or lost. There is no board but rather just one big slippery slope. “I-de” highlights one of the strategies that artists can employ to skirt appraisal and outcome in unfavorable or confusing circumstances and gain a home advantage in the process: change the rules and block the dice. Or, create a system wherein the element of luck and its properties are controlled by the artist. In other words, load the dice.

This piece is a progenitor of Duchamp’s iron, of course and the joyful cheating that characterized his work (he loaded the dice, indifferently, of course). Use the iron and you’ll rip a shirt. Pistolesi’s die cannot tumble. The useless creates sacredness. Nothing will be broken or fixed which is a pronouncement with an air of finality to it like that of a roll of the dice. Still, while “I-de” is stopped other dice are rolling and contingency is still at work.

72 centimetres (28 inches) is the standard length for table legs in the human world. This measure creates a plane transiting human domestic space across the face of the planet. This notion of measuring human presence and needs as well as the notion of canons of ideal proportion was recently encountered in this blog with the artist Antti Laitenen. Laitenen measures his existence on this earth via direct confrontation with natural forces such as tide and solid earth.

Does the natural world roll dice ? It can. In a project entitled Aqua Dice I plan to set a pair of dice out at sea and have them rolled by wave and wind action. Nature won’t use them but maybe natural forces will determine another probability curve for future rolls.

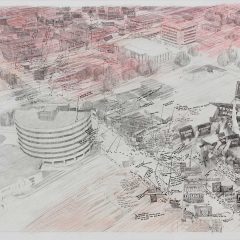

Speaking of luck, I am glad that the guillotine has been cancelled in France! While walking through the Tuileries garden in central Paris I saw what I thought was a reminder of capital punishment a la Francaise when heads, in addition to dice, used to roll. In France when upper management messes up they still say “Heads will roll!”. In fact these weren’t blades but rather the arcs of a circle. It was chilling to see such a formal coincidence near the Place de La Concorde where the guillotine was working overtime during the Revolution.