Now in its 75th go-round, The Whitney Biennial is still the big kahuna, the show every American artist wants to be in and every art lover wants to see. This year the career-boosting show includes no Philadelphia artist. We had representation in 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008 — so much for that trend. Instead, the curators went to Chicago, Oregon, Los Angeles and, of course, New York for the 55 artists, more than half of them women (a first) and many of them under the national radar.

The show is a somber parade, with some work that’s tedious and some that’s breath-takingly beautiful. A surprising number of artists are channeling anthropology ala Margaret Mead this year, a trend among Philadelphia artists as well — see Zoe Strauss, Sarah Stolfa, Phil Jackson and Gabe Martinez for starters.

Whether intended or not, this is a populist show dealing with issues of war, gender, alienation, the slipperiness of truth and longing – things very much on people’s minds. War victims show up in photographs of a disfigured American soldier by Nina Berman. Stephanie Sinclair’s photos of desperate Afghani women who self-immolate are stomach-wrenching. Sharon Hayes’ multi-channel videos about political protesters create a kind of faux-reportage that questions the reality of the news. The artist, a chunky, tousle-haired young woman, who appears throughout, exudes no star power but she’s charismatic. She’s the anti-Christiane Amanpour.

Some of the documentary films are mesmerizing, like Rashaad Newsome’s two silent videos of “vogue” dancers — athletic young men in t-shirts and jeans who spin, twirl, prance and contort themselves for the camera from small prison-like rooms. One of the dancers makes eye contact and just won’t break — it’s a challenge to pull yourself away. These silent pieces force you to concentrate on the dancers’ personalities and gender identities. Their stylized movements are not seductive but the perpetual motion alone casts a spell. It’s all very poignant.

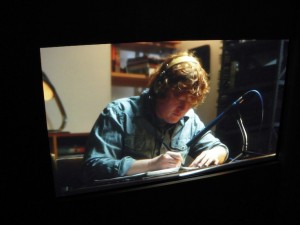

Ari Marcopoulos’ video, on the other hand, is static, colorful and loud. But it, too is hypnotic. The piece documents two teenage boys making noise music in their Detroit bedroom and, in a nice touch of curatorial pairing, the sonic screeches of Marcopoulos’ video wash over the nearby photographs of suburban tract houses by James Casebere — the very houses this noise might be coming from.

The bone-rattling machine noise soundtrack of Josephine Meckseper’s video “Mall of America,” turns what is a rather beautiful (albeit ham-handed) slap at capitalism into something mesmerizing as well. Maybe I didn’t have enough coffee the day we saw the show but I felt myself grow roots when watching this one even though I knew its message was nothing new.

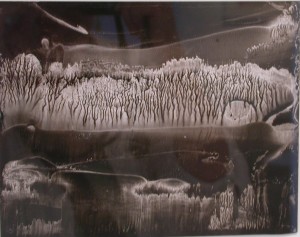

Roland Flexner’s wall of small sumi ink landscapes is the oasis into which you can escape. These drawings (like some of Flexner’s I’d seen Gallery Joe) are dark, dreamy paradise scenes. Sublime with a bit of threat they are not afraid of beauty or the infinite, something we’re very much in need of.

Tedium sets in with several inclusions that seem to be there merely to toot the museum’s own horn. I have to believe Maureen Gallace‘s chalky and standard-issue landscape paintings are there to call attention to the Whitney’s Edward Hopper and Milton Avery holdings (you can see Hopper in the Whitney Collects show on the museum’s fifth floor.) R. H. Quaytman’s photo collage prints, which feature the museum’s Marcel Breuer-designed windows, likewise seem geared to feature the museum as much as the artist.

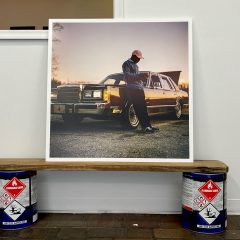

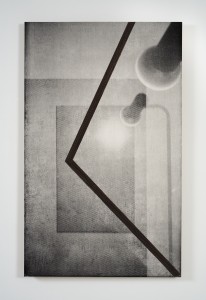

But really, the Whitney Biennial has always been about the Whitney Museum. As if to prove that point, the show’s catalog ($45, softcover) devotes more than half its pages to past biennials. This book is a big disappointment. With eight shiny card stock “billboard” pages inside showing nothing but a horrible concentric square design in black and grey with a photo (in green and white) of the sitting American president at the time of biennials in 1930, 40, 50, etc, the book is borderline annoying. And with more than half of it devoted to press clippings about past biennials — and pages and pages of lists of names of who was in each and every biennial — the book seems an almost desperate attempt at institutional cheerleading. I don’t know, maybe you have to remind people how wonderful you are when you’re in the middle of a big capital campaign.

The biggest disappointment of the Biennial is Charles Ray‘s drawings of flowers, or something that looks like flowers drawn by a teenage girl who just got a new set of magic markers. I read Peter Schejldahl in the New Yorker (see and hear his audio slide show here) and I’m not convinced. The work is slight and bad to look at, and this from an artist whose sculptures can knock it out of the ballpark. I don’t get it.

Biennials are a way for museums to claim the leadership they once had from the marketplace (art fairs/auctions) which has taken over defining what’s good and worthy. There should be more biennials. That said, no curated group show is “the answer” to the big mystery of what is art today. But, bottom line, a curated show will give you more satisfaction than the art fairs will.

More photos at Flickr.

>>Whitney Biennial 2010, to May 30. Whitney Museum of American Art, 945 Madison Ave. at 75th St. New York, NY 212 570 3600