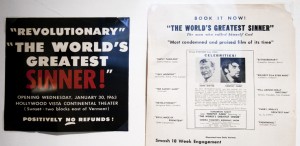

Vox Populi’s Dead Flowers—guest curated by Lia Gangitano of PARTICIPANT INC, New York—invites us to consider the spirit of the underground through little known director Timothy Carey. A vintage poster for The World’s Greatest Sinner! at the entrance of the exhibition proudly announces Carey’s film as—and suggests that any other work in the show should aspire to be—the “Most condemned and praised […] of its time.”

The best work in Dead Flowers earns that appellation by letting the tasteful and the taboo get real cozy.

Alvin Baltrop’s Pier Photographs (1975-86) are sensitively observed. A brief shock of blinding light or the fleeting poise of a half closed hand is honored by the technical comfort and intimate scale of the photographs. But the subjects of these graceful observations—meetings of queer runaways and cruisers in the abandoned post-industrial West Side piers of 1970s and 80s Manhattan—could only happen precisely where normative society failed to look. Baltrop’s photographs of overlooked spaces and covered-up activities fulfill the promise of the underground through their disarming beauty.

Putting Paul Thek’s Meat Cable (1968-9) nearby is a tidy curatorial move. Thek’s simple conceit—desiccated flesh as capacitor—turns a surprising and conventionally distasteful material into a stunning visual metaphor for stored energy.

Some of the contemporary work fares less well. Between the artworld’s pluralist mood and the Naughties’ internet-aided desensitization, it’s harder to shock than ever. Better find another way to get condemned.

Brandon Olson’s Untitled (2004), an expressionistic and colorful drawing of an ambiguously gendered heavily made-up face, is as not as transgressive as its casual construction and material choices (glitter and spray paint) together seem to hope for. Nor is its polite gender confusion or declarative glaze really stepping on anyone’s toes. It’s been 7 years since Captain Jack Sparrow hit theaters, decades since Duchamp’s alt-gender alter-ego Rrose Sélavy entered the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and over a century since Olympia stared down some surprised salon-goers. That Olson’s piece features the word “Selavy” scrawled across a cheek does not legitimize it, but, rather, only confirms that its bite is borrowed.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge’s overly sleek nude double portrait Red Chair Posed (2008) and materially sensuous but insubstantial Tongue Kiss (2003) share some of the troubles of Olson’s drawing. However, P-Orridge’s most recent piece, Boaz (2010), is a real knockout.

At first, it appears to be three impersonal medical images of patients with decreasing numbers of false teeth. But the unusual quantity and color of the teeth, coupled with a persistent mole, reveal that the series of photographs depict the same mouth.

That is, the subjects of the triptych are not three people, but three states of one person; the visible change is the number of teeth replaced with gleaming metal. Boaz’s success lies precisely in achieving these kinds of transgressions—confusions of personal and impersonal, singular and plural—through the seemingly matter-of-fact genre of medical photography.

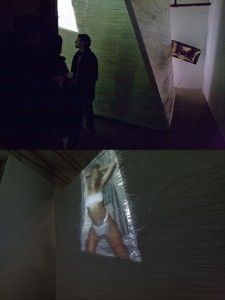

Suspiciously billed as “CG Haiti live gesamptkunstwerk with stage production by Humalode LLC,” Copy Gallery’s first Friday shenanigans filled the small space. Loud music emanated from an irregular opaque packing-tape (cling wrap?) prism, just barely smaller than the room itself—think DIY Richard Serra with killer bass. The space between the prism’s planes and the walls of the gallery was just wide enough to act as an encircling hallway.

Walking counter-clockwise around the prism, I was confronted by a series of assertive images. Affixed to the back wall of the gallery, two motorized body-sized prints of a “Predator-mouth” spun like pinwheels, lit by a bare white fluorescent tube on the floor. A projection onto the prism itself alternated between grainy overexposed photos of hard-partiers and incendiary text (“The public sector was outsourced” “WHAT ARE VIABLE MODES OF NON-IDENTIFIED COMMUNAL PRAYER?”).

Despite the prolific and generally overbearing images around the prism, the sound held its own. The strength of the vibration, the assertive but not deafening volume, and irregularity of the music revealed that it was not a recording, but a live performance masked by the prism walls.

The images in Copy managed to be both cacophonous and distant, while the live sound performance, despite the visual block, maintained a human touch. This unexpected harmony made Copy Gallery’s installation memorable and frankly pleasurable. I came back twice before the night was out.

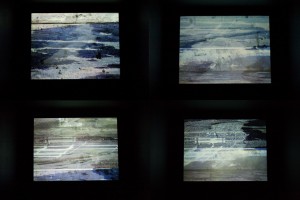

Pat O’Neill’s Horizontal Boundaries (2008), a 35mm film transferred to HD video for Screening, starts with a blank screen. In the darkened room, the sounds of city life hum, click, honk, and whir. They’re a suitable overture, as the screen lights up to an image as overlaid as the sounds. A scene of LA beachgoers reposing by, shuffling around, and crashing into the barely discernable ocean mixes with different views of the same scene and a still shot of debris on the sand. A lone figure on a bench sits, disappears, and reappears. California landscapes and crowds merge.

O’Neill masterfully uses optical printing, a technique where a film projector or projectors are synched to a movie camera recording the combined image the projectors produce. Nonetheless, the film’s (and the artist-statement’s) conceit—that the laborious overlays yield an image of representation itself, the subject represented, and the hazy “idea” of that subject—is less interesting than the resemblance O’Neill’s analog images have to digitally manipulated video. Particularly intriguing is that O’Neill’s highly crafted film resembles a genre of digital video—let’s call it youtubey—that is easily and quickly made, and critically celebrated for that democratic quality. Spending a half hour with the artisanal but strangely familiar Horizontal Boundaries, I’ll say the jury’s still out on the value of easy.

–David Muenzer fell down a few stairs in 1998. After passing a couple minutes by some tentative cursing, the soreness subsided, and he finished going to the backyard. He currently spends too much time trying to make a Tahdeeg, but, having failed to look up a recipe, generally just burns the pan.