Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman’s Bauhaus 1919-1933; Workshops for modernity (2009, Museum of Modern Art, New York, ISBN 978-0-87070-758-2), the catalog for MoMA’s exhibition of the same name, would serve as an excellent introduction to the Bauhaus for a serious scholarly or general audience. The book, as did the exhibition, addresses the Bauhaus primarily as an educational institution, rejecting common usage of the term to describe a style, often associated with modernism in general.

It is made up of introductory essays by each of the authors, thirty short articles by other scholars (which are actually extended catalog entries), and a chronology, with all 448 objects in the exhibition (and more) illustrated beautifully, in color. The essays all have notes but there is no overall bibliography; I assume this acknowledges the availability of bibliographies by Biundo and others. The many short articles not only bring a range of voices to the volume, but mark a welcome change from catalogs on modern subjects which often lack individual entries.

Bergdoll discusses Bauhaus pedagogy and marketing (through exhibitions and publications), noting its background in the writings of Muthesius, Semper, Riegel and others. He discusses the ambition to reform life as well as teaching, the school as a model city, the ideal of the house as modern Gesamkunstwerk, and the ongoing tension between unique objects versus reproducible objects of industrial production and between universal functionalism and individually-credited designs. Dickerman sets the Bauhaus within a post-WWI interest in anti-nationalist universalism (which abstraction was thought to support), an emphasis on teaching through craftsmanship (with precedent in craft schools, but not art schools), and learning through the sense of touch as well as sight.

The series of tightly-focused studies point to the interaction of theoretical, political and personal inclinations in determining how the various Bauhaus figures made decisions about design, production and pedagogy. This gives a nuanced approach to the practices of a large and divergent group. For instance, Juliet Kinchin in discussing Theodore Bogler’s ceramics in light of his post-war turn to primitivist craft as a conservative stance emphasizes the potential of artistic modernism to reflect either conservative or socialist politics. Frederic J. Schwartz discusses the paradox of a socialism of vision embodied in Wagenfeld and Jucker’s classic table lamp; their employment of pure forms was an implicit retreat from real politick during a particularly fraught time in Germany.

Interactions in Color

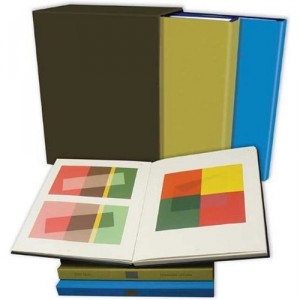

I have been waiting forty years for Joseph Albers’ Interactions in Color (2nd edition 2009, original edition1963, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-14693-6). The original edition was published as two portfolios of unbound folders and I saw a number of them in an exhibition in the mid-1960s. I assumed such a recent publication would be available, but the only thing I found was a much abridged paperback, various versions of which have been available since 1963 in multiple languages.

The original Interactions in Color was unlike anything Yale University Press (YUP) had produced; the press took up the project understanding that it would have to meet the standards of Albers, who was uncompromisingly demanding and precise. During the writing and production the press’ director and Albers stopped speaking for an entire year. But the results were a marvel, and it quickly sold out. It was not a treatise on color, but a set of exercises meant to inspire readers to take up their own color experiments.

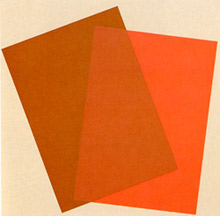

Albers taught color without a system like Chevreul’s color wheel, or Munsell’s and Ostwald’s three-dimensional models (although he discusses and illustrates the last two). His was a lesson in seeing; as he said, Our concern is the interaction of color; that is, seeing what happens between colors. His exercises were empirical. The book follows the lessons he taught for 36 years, first at the Bauhaus, then at Black Mountain College and finally at Yale University. Something of his attitude as a teacher can be seen from the book’s dedication, which is to his students who, Albers says, have taught me more color than have books about color. I took a color course with one of those students who closely followed his method and can testify to its rigor and value. An editor at YUP told me the re-publication was inspired by talking with an artist who convinced her that its availability would be of great use in teaching. It certainly will be.

The new edition, bound in two volumes – one text, the other color plates — is beautifully printed and conceived, down to the cloth covers which, when laid side by side, are seen to be one of Albers’ exercises. It closely follows the original design which Albers worked on with Norman Ives, although the plates do not have anything like the richness and intensity of the original edition, which were silk-screened; they looked just like the Color-aid papers we used for exercises. But it is still a luxurious book, with movable flaps for some plates, to mask areas or add comparative examples, and a number of the free studies he set after the students had gone through the structured ones. It also includes an introductory essay by Nicholas Fox Weber on the history of the book’s production and something of its reception. Readers of the back matter will see that the plates were done by a number of Albers’ students, including Eva Hesse, Rackstraw Downs and the poet, Mark Strand.

Albers at the Hirshhorn

Josef Albers: Innovation and Inspiration, on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden through April 11, is a good introduction to Albers’ pedagogy. His work is represented by paintings, stunning works in glass, works on paper and pages from the original, silk-screened edition of Interactions in Color (mostly drawn from the museum’s own collection). The artist worked at night under artificial light, using pre-mixed colors and a palette knife. He did everything to eliminate evidence of his hand, but time and the inherent texture of the fiberboard on which he painted has resulted in paintings that carry his intent less well than the still-uninflected silkscreen surfaces of the 1963 publication.

Perhaps as interesting as Albers’ own work is the small selection of work by artists he taught and/or influenced, including Robert Rauschenberg (the placement of the small amount of red in Dam clearly reflects his study with Albers), Donald Judd (I’d never before realized how much his stacks drew on Albers’ studies), and Jacob Lawrence (I’ll never look at his work the same way again, particularly the relationship between close colors within areas).

Just as interesting was exiting the exhibition into the Hirshhorn’s interior, circular area where the museum permanently displays sculpture. The Hirshhorn shows the most complete selection of 20th century sculpture of any museum I can think of, despite the fact that all are of modest size, even those by artists who usually worked on larger scale.

Two works in particular struck me: one of Larry Bell’s cubes, with subtly colored iridescence; and one of Hans Haacke’s condensation cubes, from the period when Haacke was working with natural systems. After looking at all of Albers’ squares they emphasized how central the square, and in 3 dimensions the cube, were to art of the 1960s. They also reminded me how hard it must be for later generations to know these works, other than as illustrations in books, slides or on the web. It’s not the same, and we should be grateful to the Hirshhorn for keeping this work on view.