Old City brought the crowds on first Friday. The five o’clock crawl gave way to 6 o’clock jams, and by 7, the 20 and 30 somethings outnumbered the slightly older early-birds. So what’s the draw?

The Clay Studio’s flagship exhibit for the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts annual conference has a ponderous name: “Of this Century: Residents, Fellows, and Select Guest Artists of The Clay Studio, 2000-2010” (through May 2nd). Like the title, the show is large, organized by convention, and conveys less than its ought to for its length.

As a survey show, it might seem unfair of me to harp on curatorial choices (or lack thereof). But since there is, as a given, a degree of sameness to the pieces in a Clay Studio show—a shared penchant for demonstrated virtuosity and dishwasher-size—it is a special disservice to works in “Of this Century” to obscure their particularities through a homogenizing grouping.

Claire Curneen’s porcelain and gold figural sculpture Lucretia is a prime example of the strengths and weakness of the works in the show. Curneen coaxes, with an unfussy additive sculpting process, convincing gesture from the clay figure. The facial features are likewise concise and poised—the eyes are reduced to dot-notations and the mouth an inset dash. The figure’s more modeled hand stabs the stomach, letting out a small flow of blood, rendered in gold leaf.

Lucretia, for all its deftness, fails to move me. It’s “sculptorly” simplifications, classical subject, and use of a literally precious material seem to reach for a weighty art-historical lineage: Rodin’s modern imbrication of form and material, the Kouros’s antique hope for perfect beauty, the Venus of Willendorf’s primal directness.

But attempting to combine these distinct modes precludes the form that would actually constitute any one of them. The simple face, for instance, does have an arresting combination of specificity and vagueness—albeit somewhat closer to Julian Opie or Sandro Chia than a Kouros—but the baroque flourish of the gold and laborious, modeled hand bars reading the simplifications in the piece as a metaphysical posture.

I feel similarly ambivalent about many of the pieces from Old City’s first Friday; time and again, I saw artworks intimating powerful meanings that their forms could not carry.

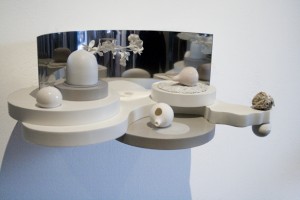

Julie York’s Reflectionoitcelfer series—with a handful of pieces in the Clay Studio and a half-gallery of works at Pentimenti—are very different from Ms. Curneen’s sculpture, but subject to a similar critique.

York’s abstract ceramic tableaus place irregular and geometric shapes side by side on supports that look like miniature 1950s game show sets. The whole scene is mirrored and distorted by an arc of metal curving behind.

York’s pieces successfully confuse the organic and the inorganic—a strange ball of fiber sits above an “ideal” ceramic sphere in one piece—as well as the large and small—the set-like quality of the platforms coexists with a one-to-one scale flower. My favorite moment is a perfect half-sphere that seems to turn into a fried egg as it makes contact with its support. Because it is rendered in a single piece of ceramic, it demonstrates physical continuity between geometric ideals and the rude informality of the edible.

Such challenges to conventions of rationality are central to the best works of art. Yet, presented too transparently, said challenges start to feel like rational exercises themselves: this round shape calls for a squiggle, these bundles call for a solid form, that natural needs an artificial. To everything, logically, its opposite!

York’s pieces please, but neatly lined up on the wall, the sculptures’ efforts to tangle experience are unwound. The repetition of techniques turns hard-to-parse moments like the fried sphere into a bit of a vocab list, easy enough to memorize, then utilize.

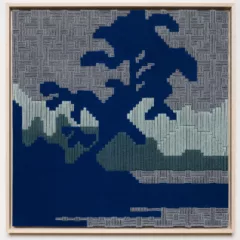

The repetitions in Viviane Rombaldi’s works at Pentimenti function in the opposite way. While excessive continuity trips up York’s project, Rombaldi interprets the same material to wildly differing degrees of success.

On its own, Rombaldi’s collage Boomerang is a striking revaluation of a newspaper. Where one might expect to see facing pages and horizontal type, Boomerang instead greets its audience with two delicate spirals of collaged-newspaper text.

I was struck by the extreme fragility of the configuration—it must have been painstaking to collage these thin strips of newsprint in a controlled manner—and the boldness of the mark—the spiral is visible even among information-saturated attention-grabbing newspaper clippings. By producing such tension in something as supposedly straightforward as a broadsheet, Romaldi shows us how unstable the seemingly basic act of “reading the morning paper” can be.

But flanking Boomerang on either side are Fougeres and Woodlands, in which newspapers are cut into plainly illustrative shapes. In these pieces, the final shape of Romaldi’s work makes no reference to the design of a newspaper, and the subtlety that Boomerang achieves is, accordingly, absent.

Adelaide Paul’s exhibition “The Peaceable Queendom” at Wexler gallery (through May 1st) presents similarly uneven work, with the potency of the central material, once again, only occasionally realized. In the best pieces, taxidermy manikins have been lightly modified to great effect. These simple changes generate uncomfortable hybrids: an evocative yawn from a three legged dog or an inquisitive stare exists in the same space as a still-recognizable taxidermy manikin, which we are uneasily aware could well have been used instead to display a real dog’s carcass.

.

Unfortunately, Paul does not always show such discretion. In most of the show, she favors complex dramatic poses and baroque ornamentation, which discourages considering the strangeness of the manikins. Accordingly, the poetry of the animated taxidermy, present in the two smaller works, is lost.

My favorite piece of the night was Bruk Dunbar’s small ceramic bus from Dalet art gallery’s “The Travel Show” (through April 27th). Dunbar’s piece does, in under 4 square feet, everything Dalet’s other show—the large, largely mediocre, and pretentiously titled “Birth of Shape”—fails to do.

Dunbar’s cartoony bus tapers as it goes back, seeming to speed forward through an anamorphosis effect. But unlike most times such trickery shows up in art, we can be disillusioned as we walk past the sculpture, and see the awkward distortions from the rear.

This failure to zoom, rendered in strong glazed color and brittle ceramic, is announced by the heavy title: The Silver Bullet Will Become A Ghetto Pod. Yet, as skeptical as Dunbar’s piece is about the unbridled optimism of the modern, it is not pessimistic. The reflections of light on its glassy surface, still-brilliant green hue, and obstinate charge frozen in time, give us a fleeting sense of the beauty and total futility of the modern dream.

–David Muenzer fell down a few stairs in 1998. After passing a couple minutes by some tentative cursing, the soreness subsided, and he finished going to the backyard. He currently spends too much time trying to make a Tahdeeg, but, having failed to look up a recipe, generally just burns the pan.