Post by Colette Copeland

Everyone complains that New York is dead in the summer. I braved the heat on Tuesday venturing to the International Center of Photography and down to Chelsea. While many galleries were closed or in the midst of installing a new exhibit, there were a few welcome surprises, proving that even in the ‘dead’ season, New York is worth the trip.

Everyone complains that New York is dead in the summer. I braved the heat on Tuesday venturing to the International Center of Photography and down to Chelsea. While many galleries were closed or in the midst of installing a new exhibit, there were a few welcome surprises, proving that even in the ‘dead’ season, New York is worth the trip.

Daguerrotypes

On display at the International Center of Photography through Sept. 4 are the 19th century daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes. The duo collaborated from 1843-1863. The exhibit is astounding on many levels. I have never before been in such close proximity to so many pristinely preserved daguerreotypes (top, unidentified bride, ca. 1850).

On display at the International Center of Photography through Sept. 4 are the 19th century daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes. The duo collaborated from 1843-1863. The exhibit is astounding on many levels. I have never before been in such close proximity to so many pristinely preserved daguerreotypes (top, unidentified bride, ca. 1850).Most photographers I know suffer from varying degrees of daguerreotype fetish. The daguerreotype’s aura stems from its rarity, uniqueness, and irreproducibility, causing photographers to swoon in its presence. I am no exception to this phenomenon. Unlike other photographers at the time, Southworth and Hawes worked with large 8” x 6” plates, giving their images an added “ooohh factor”. Given the labor-intensive and costly process, only the wealthy could afford daguerreotypes. The process also involved handling toxic mercury vapors during development, which significantly shortened the photographer’s lifespan (right, Miss Sarah Hodges of Salem, Mass., ca. 1850).

Most compelling (perhaps because they are less commonly seen) are the post-mortem child images and the images of early, public theater-style operations using ether. Both present their subjects in a state of sleep–the former in permanent stasis and the latter in a temporal state. While early photography’s role was to document and record, Southworth and Hawes brought an artistic sensibility to their compositions, evoking an emotional quality lacking in other photographers’ works from the time (left, postmortem unidentified child, ca. 1850) .

Most compelling (perhaps because they are less commonly seen) are the post-mortem child images and the images of early, public theater-style operations using ether. Both present their subjects in a state of sleep–the former in permanent stasis and the latter in a temporal state. While early photography’s role was to document and record, Southworth and Hawes brought an artistic sensibility to their compositions, evoking an emotional quality lacking in other photographers’ works from the time (left, postmortem unidentified child, ca. 1850) .Lastly, daguerreotypes have to be physically experienced. Years of looking at crappy slides and reproductions in art- and photo-history classes only enhanced my awe in seeing the real deal in person. Virtual does not even come close.

Jesus surprise

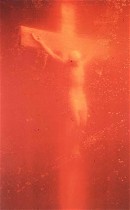

In Chelsea, I stumbled across the show, “Jesus Christ Superstar: 140 Years of Jesus Christ in Photography” at Bruce Silverstein Photography (thru July 29). The exhibition featured 48 photographers, whose work spanned the movements of pictorialism, surrealism, modernism, and postmodernism. This was clearly a ‘best’ of show. Most of the work was familiar and there were some predictable choices like Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” (right), and Renee Cox’s “Yo Mama’s Last Supper” (below, left).

In Chelsea, I stumbled across the show, “Jesus Christ Superstar: 140 Years of Jesus Christ in Photography” at Bruce Silverstein Photography (thru July 29). The exhibition featured 48 photographers, whose work spanned the movements of pictorialism, surrealism, modernism, and postmodernism. This was clearly a ‘best’ of show. Most of the work was familiar and there were some predictable choices like Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” (right), and Renee Cox’s “Yo Mama’s Last Supper” (below, left).  There were a few surprises however, which added to the complexity of the exhibit. Jose Maria Sert’s vintage black and white print from the late 1930’s depicted the descent from the cross, using featureless wooden anatomical dolls. In the Russian constructivist style, photographer Marinus created a montage photograph in 1940 combining Hitler and Jesus. Neither of these photographers is included in the photo history books, so it was treat to see their work.

There were a few surprises however, which added to the complexity of the exhibit. Jose Maria Sert’s vintage black and white print from the late 1930’s depicted the descent from the cross, using featureless wooden anatomical dolls. In the Russian constructivist style, photographer Marinus created a montage photograph in 1940 combining Hitler and Jesus. Neither of these photographers is included in the photo history books, so it was treat to see their work.

What caused the exhibit to successfully transgress the surface level was the juxtaposition of the work.

What caused the exhibit to successfully transgress the surface level was the juxtaposition of the work.

Early 20th century pictorialist, F. Holland Day’s sincere tableaux self-portrait crucifixions sharply contrast the crucifixion performance spectacle of Hermann Nitsch.

Documentary photographs by Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Walker Evans, Robert Frank and Eugene Smith recontextualize the ironic tone of such work as the four different renditions of the Last Supper.

Rolling Stone photographer Annie Liebowitz’ Last Supper features the cast from HBO’s hit series, “The Sopranos”.

Vik Muniz’ Last Supper (right) is brilliantly painted in chocolate syrup and then photographed, while still wet.

Cox’s version features herself as a nude black female messiah.

New to me was Raoef Mamedor’s 1998 Lambda print of Jesus and the apostles played by models with Down’s syndrome. I have to admit, this version did not strike me as funny at all, but rather exploitative. Perhaps the artist shares Joel Peter Witkin’s view on celebrating those who are marginalized. (His work was in the show too.)

Next to Chip Simon’s 2003 color photograph entitled, “Jesus Toast” (wasn’t that toast sold on e-bay for thousands of dollars?) was the 1898 albumen print authenticating the Shroud of Turin.

A few prints down, plastic surgery queen and French performance artist Orlan’s “Saint Suaire #21” eerily referenced the Turin Shroud. One could argue that this was a cheap shot—a parody at best. However within the context of the entire exhibition, a dialogue emerges. Beyond the obvious subject matter, questions of mortality, authenticity, and the search for meaning surface.

Whether the photographers are documenting the evidence of Christianity in contemporary culture or critiquing/questioning notions of history within the framework of Christianity or venerating Christ as an icon, the fact remains that JC as a subject has continued to reign in the art world and in photography since its inception.

–Video artist Colette Copeland teaches at the University of Pennsylvania and at the University of the Arts