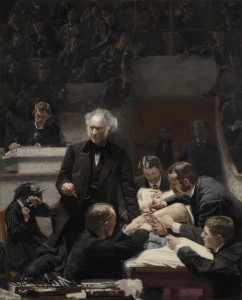

The restoration crew at the Philadelphia Art Museum likes to say that The Gross Clinic now looks like it did when it came off Thomas Eakins easel in 1875. Only partially true. The way it is presented in the Museum’s Perelman Building is nothing like the debut the painting had at the 1876 Centennial Expo in Fairmount Park.

Young Thomas – barely into his 30’s – conceived and executed his masterpiece for the express purpose of getting it into the Expo’s juried show. In what is now considered one of the 19th century’s great art disasters, it wasn’t. The painting was shown out of competition, out of the Expo’s art gallery, hung in a corner behind a collection of then-modern medical equipment in glass cases. Hardly anyone saw it.

A wise man once said: nobody puts baby in a corner. The Museum has now put the restored Gross Clinic in a shrine, surrounded by its own studies. The Gross Clinic is a big, black painting – even more so after the much-needed restoration – and it reflects incandescent lightbulbs like a champ. In earlier gallery situations (i.e. Jefferson Hospital), looking at this painting meant shifting yourself around until you found the spot where the painting didn’t reflect back the glare of the lights. If you ask Museum curator Kathleen Foster, she might demonstrate for you the little dance shuffle she had to do when in front of the painting at Jefferson.

Foster knows that the best way to honor such a richly dark painting is to put it in a dark room, carefully and sparsely lit. Dr. Gross’ wide, bald forehead exploding wild strings of grey hair leaps out of dark at you, as do his bloody fingers still cradling the scalpel he used to slice open the leg of the patient to his right. His crimson fingers are just inches away from those of the patient’s mother. Her fingers palsied in horror.

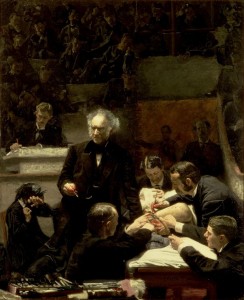

In the darkness behind Gross are students observing the operation. A restoration effort in the 1920’s erroneously presumed that we are supposed to be able to see those students. Actually, we’re supposed to see just Dr. Gross, his calm medical intellect emerging from a grisly nightmare. Had Eakins wanted those students to be seen, he would have painted The Agnew Clinic. Which he did. It’s hanging in the Perelman Building right next The Gross Clinic. Painted 12 years later, The Agnew Clinic’s operation theater is lit like a kitchen. Every student in the background (who collectively commissioned the painting) is distinctly identifiable. Dr. Agnew is dressed in sterile whites – as is his medical staff – and his jolly arms are outstretched like he has just made a Thanksgiving toast. The Gross Clinic, on the other hand, was painted before doctors understood sterility, suggesting the medical profession was coming out of the Dark Ages and there was a lot of pain involved. And maybe a little regret.

The exhibit – like the Matisse exhibit at New York’s MoMA – literally gets behind the scenes with x-ray displays of what the under-painting looks like, so you can see the artist’s method and maybe glean something about his intention. It adds to the drama. There are good guys and bad guys. The video documentary in the back room gives an excellent demonstration of how earlier restorers screwed the pooch; in the restoration community, Eakins’ work is well-known to have been damaged by good intentions. The restored masterpiece shows what Eakins originally meant, and the good, the bad, and the ugly of how the world treated it.

See the restored Gross Clinic at the Perelman Building, PMA, until January 9, 2011.

*Photo credits: Thomas Eakins Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), 1875, Oil on canvas, 8 feet x 6 feet 6 inches (243.8 x 198.1 cm)

Gift of the Alumni Association to Jefferson Medical College in 1878 and purchased by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2007 with the generous support of more than 3,500 donors, 2007, 2007-1-1