I stopped by the Perelmann Building at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) over the weekend thinking I’d spend an hour at the exhibition of North African Jewelry, and after three hours I left, only because the guards were trying to close the museum.

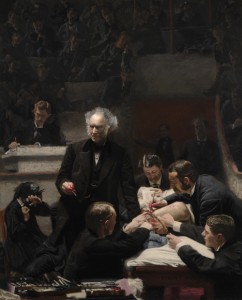

An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing ‘The Gross Clinic’ Anew (through Jan. 9, 2011), which Peter Crimmins discussed here is an exemplary demonstration of how a museum can renew the public interest in an old favorite. I suspect every visitor will learn something new about the painting, Eakins, masterpiece, and a very expensive, recent acquisition by the PMA which it is sharing with The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA: information on the purchase can be found here ) .

Crimmins discussed the exhibition installation, with The Gross Clinic hanging beside Eakins’ later portrait of a doctor surrounded by his students, The Agnew Clinic (1889), and the technical information which documents its recent restoration. The exhibition does even more. The first room situates the painting in terms of its origins in Eakins’ self-promotion, painting his largest work yet so it could be viewed in the 1876 Centennial exhibition in Philadelphia; in terms of the spectacle such exhibitions offered the public and the fact that the Centennial exhibition included the first ever survey of American art; within memories of the recently-ended Civil War, for Dr. Samuel D. Gross had written the standard work on military surgery, widely used by doctors on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line; in terms of Eakins’ medical portraiture which he initiated in 1874 with Dr. Benjamin Rand, also on view; and within the contemporary responses to The Gross Clinic, which must be as divergent as any painting has ever received.

The second gallery holds one of the most beautiful installations I’ve seen at the PMA, an institution that does such a seamlessly-good job with most exhibition design that no one remarks about it. It is also the first exhibition to use that particular gallery well. Plain Beauty: Korean White Porcelain/Photographs by Bohnchang Koo (through September 26) has a white vitrine, holding white porcelains, bisecting the long dimension of the gallery whose walls are hung with very large either black and white or color (in this case white-on- white) photographs. It is a tribute to the subtle poetry of monochrome, and indeed, to the range of colors that the term white encompasses.

While porcelain was developed in China before its production spread across East Asia, the taste for plain white ware is characteristically Korean. The vitrine holds pieces made from the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) as well as Joseon-inspired work by contemporary Korean potters. The early work is milky or snowy white, while the later work has hints of gray and blue (according to the museum’s literature; I’d probably describe some of the recent pieces as pale celadon).

The photographer Bohnchang Koo (Korean, b. 1953) began exploring specifically-Korean subject matter in 1998 with the series Masks. The huge prints shown at the PMA, with their very narrow chromatic range, convey the impression, rather than the precise forms or surface details, of this most subtle type of ceramics. In one black and white series, Moon Rising II, a globular jar stands in for the natural form and the changing lighting across the six prints mimics the effects of the diminishing light of nighttime.

One gallery over is the exhibition I’d come to see: Desert Jewels: North African Jewelry and Photography from the Xavier Guerrand-Hermès Collection (through Dec. 5). It is really two exhibitions sharing the same space. On the walls are a group of 19th century photographs of North Africans taken by photographers from France, Scotland, Spain, Syria and Turkey. Some are street scenes, others studio shots; a fair number of the later offer the same low-grade titillation that is a specialty of National Geographic, with dark-skinned women baring their breasts. While most of the photographers are known, their subjects are all anonymous and described only according to ethnic group. I assume they are exhibited for the jewelry that some of the men and women are wearing, but they would fit more comfortably into an exploration of 19th century Orientalism. This sort of ‘ethnographic’ photography has been subject to a great deal of very interesting analysis, but you wouldn’t know it from the museum’s labels.

The second exhibition is a large array of 19th-20th century jewelry; they are labeled to indicate their area of origin, likely date, materials and sometimes the techniques employed. The jewelry is wonderful, with intricate filigrees, granulation, and chased designs and heavy beads of coral, copal, amazonite, shell, glass and modern plastics. Three stone molds for cast pieces are exhibited along with two wall texts, one devoted to a brief discussion of the metalworking techniques. However, for an exhibition of artifacts likely to be unfamiliar to most viewers, the amount of content is woefully scarce.

The exhibition raises more questions than it answers: Was the work made for local use or for trade? Did craftsmen move among ethnic groups or did the techniques and motifs travel as the jewelry was traded? When was such jewelry worn? How valuable was it locally? Was the wearer exhibiting the family’s entire wealth? Did the various stones have local meaning? Who wore the amulets and did different motifs have distinct functions? Was the sound made by the jewelry when worn important?

The Eakins exhibition demonstrates the value of situating paintings from our own recent past within a social, historic and technical framework. To exhibit jewelry from unfamiliar cultures merely as beautiful baubles is shortchanging the visitors. The exhibition in the final gallery, Hanging Around: Modern and Contemporary Lighting from the Permanent Collection (through Oct. 10) is also a stunning display, but with no more information about the lamps than one would find in a commercial gallery or furniture store. The Museum should have more to offer.