The art and artifacts in these two exhibitions are more interesting for their stories than for their aesthetic qualities, but a good story is a valuable find.

Archaeologists and Travelers in Ottoman Lands at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (the Penn Museum, through June 26, 2011) focuses on three men involved with the first American archaeological expedition in the Middle East. If the Penn Museum is airing its dirty laundry in public, at least it’s an entertaining sight. Filled with feuds, fraud, coercion and madness, the tale of the excavations at Nippur (in present-day Iraq) would make a good movie or tv mini-series.

Osman Hamdi Bey was director of the Imperial Ottoman Museum in Constantinople, but his first love was painting. Having studied in Paris with academic and Orientalist painters and exhibited in the Exposition Universelle, he set up and taught in a school in Istanbul modeled on the École des Beaux Arts. Hamdi Bey oversaw the Imperial Ottoman Museum’s construction and although untrained, turned to archaeology. He made an enduring impact on the cultural patrimony of the Ottoman Empire when in 1883-84 he wrote the law prohibiting export of archaeological material.

The German-trained Hermann Vollrath Hilprecht was Professor of Assyriology at Penn. He claimed to be too delicate to carry out actual excavations (complaining about the bugs, beggars and his colleagues) so oversaw the Nippur site from a desk in Istanbul, and later from Philadelphia. He nonetheless took credit for ten years’ worth of finds at the site. Ultimately accused of faking work and stealing artifacts, Hilprecht was forced to resign his professorship.

The most sympathetic character is John Henry Haynes, the little-known photographer of the excavations. Although he spent more time at the site than any of the American expedition and personally uncovered 30,000 cunieform tablets, credit for his discoveries was claimed by Hilprech and much of his photographic work remains unpublished. Broken down by years’ of isolation and danger at the site and by the theft of his work, Haynes was too fragile to testify against Hilprecht and ended up in an asylum. A number of Haynes’ photographs are on view as is documentation and correspondence around the excavation and ensuing controversies.

While export of archaeological finds had been outlawed, the government was allowed to donate artifacts and the exhibition includes a clay slipper sarcophagus, one case of cunieform tablets (from a collection of 30,000) and another filled with incantation bowls and fertility figures, just a small part of the collection which was given to Penn. The University apparently sweetened the deal with an honorary degree for Hamdi Bey as well as the purchase of two of his paintings. The larger, At the Mosque Door, had been rolled and in storage for the last 100 years. Cleaned and given pride of place, it’s as good an example of the genre as any; it also raises the question of whether an imaginary scene of the Middle East painted in the French academic style by an educated Turk can truly be considered Orientalist; it may just belong to a class of its own.

The exhibition was organized by Penn Professors Robert G. Ousterhout and Renata Holod with assistance from students in the Halpern-Rogath Seminar in the History of Art.

Yokahama Prints at the PMA

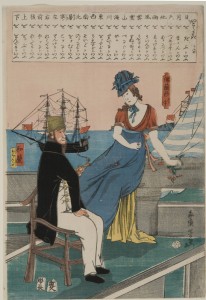

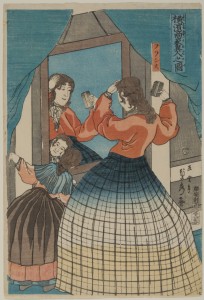

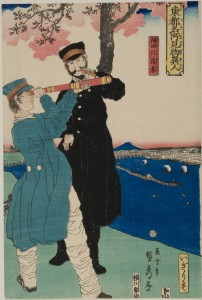

After two centuries of almost total isolation Japan signed treaties with the U.S., France Britain, the Netherlands and Russia in 1858. This opened doors to the movement of people and goods in and out of the country and provoked curiosity on all sides. The exhibition Picturing the West: Yokohama Prints 1859–1870s at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA , through Nov. 14, 2010) displays 98 wood-block prints (all from the Museum’s collection) produced in Japan to satisfy local demand for knowledge of the strangers in their midst, and display a mixture of fascination and discomfort.

These are not the beautifully-crafted ukiyo-e wood-cuts depicting Japanese life, whose export would have so much influence on Western art. They are, rather, predecessors of the fashion and picture magazines of recent times. They display a mixture of surprise at the foreign customs (such as a couple holding hands in public or women on horseback) and a bottomless hunger for details of fashion in both furnishings and clothing. If we are used to the simplified and stereotypical depictions of the Japanese by the likes of W.S. Gilbert and Giacomo Puccini, these prints invert the view.

Many of the images were not done from life but were lifted from Western magazines such as the Illustrated London News. They reveal an intense interest in women’s bare shoulders, ribbons, bows, ruffles, pleats and other foreign adornments, and an equal interest in male haberdashery. Every epaulette, braided trim, button-hole and pocket is lovingly (if not always accurately) depicted, as are the chandeliers, carpets, furnishings and framed pictures on the walls of the foreigners’ homes. Prints show such odd customs as brass bands, hot-air balloons and professional photography studios as well as the beginning of a tourist industry, with foreigners viewing the famous sights of Edo. These prints offer a splendid answer to Robert Burns’ desire to see oursels as ithers see us.

The exhibition was organized by Shelley R. Langdale, Associate Curator of Prints and Drawings.