Rebecca Jacoby, one of two artists featured at LG Tripp this month, has a bright pastel palette after my own heart. Many of her works are done in acrylic, oil, pastel and collage. For such a wide array of media, she utilizes her materials in a way that they are blended beyond individual identification, making her pieces very cohesive and whole.

The natural and nonobjective forms in Jacoby’s works are reminiscent of plankton or aquatic creatures swimming in some primordial soup. Bubbles and globules ebb and flow on her canvases much in the same way that her process reveals itself to her.

Unintentional marks that occur whilst preparing her canvas serve as the starting point for other forms. Jacoby says that “these marks are catalysts from which I expand on imagery and move the work forward.” She then works and reworks the pieces to completion, mirroring real evolution not only in biological appearance, but also process.

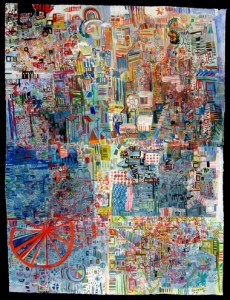

Miriam Singer, the other featured artist, makes a good contrast to Jacoby with her intricate drawings. Whether traveling around town or sitting in airports, Singer often carries her art around with her, working on her drawings much in the same way one would approach a sketchbook. Using whatever writing implements she may have available, she builds small urban environments across her pages.

Once at the studio, Singer applies various screen printing and woodblock techniques to the drawings. The printing surfaces’ limited size (as well as frequent folding of the paper for portability purposes) gives her larger works a grid-like composition and additional depth.

These little landscapes have distinct neighborhoods of their own that are reflective of the diverse and colorful nature of real cities. Often geometric and sometimes crowded, the subtlety of every pen stroke and idiosyncrasy makes these little communities dynamic enough to feel real.

Over at the Bridgette Mayer Gallery, most of the space is dominated by Charles Burwell’s large-scale studies of that tenuous place between the geometric and the organic. These paintings involve layering and dripping paint and shapes over one another to construct intricate patterns of great depth. These are op-art excursions that would put even Hunter S. Thompson’s wardrobe to shame.

Aside from their scale, they are impressive also for their sense of movement. The direction of that movement, however, is anyone’s guess. Flower-like forms seem to spin over curved lines, which dip beneath bulbous forms and slide under more lines, all of which lie beneath stripes of striking hues.

Burwell’s compositions seem wild and random, but upon closer inspection it is evident that they are extremely calculated and precise. The only thing more mind-blowing than these heavily-saturated explosions themselves is the realization of how much time they must take to produce.

More humble, and in this instance truly random, are Clint Takeda’s prints in the back vault of the gallery. He was happy to explain the background of each, and they all have curious individual narratives behind their creation, like dropping ink-covered rubber bands over wood prints or dripping iodine onto paper.

What emerge are unique, yet strangely recognizable natural forms. Some are celestial and distant while others look curiously figurative. They are all created rather randomly, and at least one utilizes the old oil and water adage in practice to shape an image that is otherwise irreproducible.

While these shows run the gamut of styles, there is a reminder in their divergence: that process is the backbone of visual – and perhaps any – creative endeavor. Whether explicitly or not, the journey is just as important as the destination.