People trained in clay, glass and fiber often wonder why their work is marginalized within the art world and relegated to craft. I suspect it’s because much of the work puts an emphasis on technical virtuosity (a subject that never arises in discussing contemporary art which, these days, is likely to favor the quick and dirty solution) and does not engage issues of interest to the wider art world.

Here are two books, one on an artist who works in glass, the other on ceramics, which should interest readers across disciplines.

Josiah McElheny; A Prism. Louise Neri and Josiah McElheny, eds. (New York: Skira Rizzzoli, 2010) ISBN 13: 978-0-8478-3415-0

Josiah McElheny; A Prism is the first overview of a particularly inventive and intelligent artist whose work long ago obviated the question of art vs. craft. It is also that rarity these days: a monograph unconnected to an exhibition. This allows a range of work to be represented which could never be physically assembled. The book emphasizes McElheny’s production of the past decade, with essays (largely reprinted from catalogs and journals) by fifteen authors as well as writing by Jorge Louis Borges and Adolf Loos that were significant for the artist. The authors include artists, critics, curators, art historians and a cosmologist. McElheny’s own writing is included, as are his conversations with Louise Neri, recorded over a long period, which are threaded throughout the book.

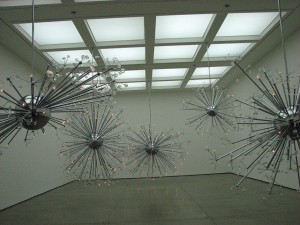

McElhenny reads widely. His research engages a range of questions that his installations address: modernism, history, the social implications of design, the unity of the mind and senses, the place of models in architectural thought, how display of collections changes individual objects, the significance of unbuilt projects, the symbolic place of glass in architecture, and the theory of the universe. His work incorporates his sources, variously intertwined and often in fictional relation to one another, and is replete with verbal and visual citations. The book is successful in conveying the complexity of his thought and work, as well as its visual form.

The artist was trained as a glassmaker, a craft that has barely changed in several thousand years, and the conceptual basis of his installations often involves the relationship of art and craft, the unique and the multiple, and the individual artist and collaborative craftsmen. Despite the extensive intellectual background, the first impact of the work is always aesthetic and sensual. McElhenny produces extremely beautiful art. The book’s extensive color images document this extremely well, with multiple views and many details.

It’s a very handsome volume, despite the fact that the effects of glass are almost impossible to capture with photography. Glass is inherently reflective, more so when mirrored, as some of McElheny’s work is. Reflections change as viewers move and McElheny’s installations are often large enough that reflections come from multiple angles, creating a flickering environment. It is noone’s fault that the illustrations will never have the immersive and changing effects of their subject, nor the impact of their large scale.

The book’s design, by Purtle Family Business, is as conceptual and multi-referenced as the artist’s work. Each essay is separately laid out and set in a different type, and McElheny suggests in his introduction that readers will be able to tease out the meanings from the articles. Much as I’m interested in graphic design, I’m not educated enough in its history to recognize the referents; but readers who d o will have the pleasure of figuring out another of the puzzles that pervade McElheny’s work.

The Hockemeyer Collection; 20th Century Italian Ceramic Art (Hirmer Verlag, Munich: 2009) ISBN 978-3-7774-2271-8

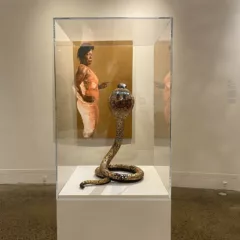

The Hockemeyer Collection; 20th Century Italian Ceramic Art reveals a subject that is almost entirely unknown to English-speaking audiences: modern Italian ceramics, with an emphasis on work from the 1950s-60s. The works illustrated are from a collection assembled by Bernd and Eva Hockemeyer of Bremen. The bilingual volume (German/English, with an Italian insert) is a serious and scholarly book, with a long article situating the work by Lisa Hockemeyer (the collectors’ daughter, who has a doctorate in the field of Italian ceramic art), entries on each work, a substantial biography for each artist and a bibliography.

Lisa Hockemeyer’s very interesting article explains the historical situation that distinguishes ceramic production in Italy from the tradition of studio ceramics in the U.K. and U.S. The Anglo/American studio craft movement began in the late 19th century as a return to handwork, in reaction to industrialization. Industrialization did not pervade Italy until the 1960s, and the country had an unbroken tradition of ceramic production in numerous regions where many of the workshops remained relatively unchanged since the Renaissance. The use of ceramics in the fine arts was also bolstered by the precedent of Etruscan ceramic sculpture, Renaissance majolica and the sculpture of Luca Della Robbia. The Italians did not make strong distinctions between crafts and fine arts or high and popular culture. This allowed artists working in ceramic, many of whom had much better known careers as painters and sculptors, to draw upon craft traditions while exploring the current concerns of their art.

The situation in Italy encouraged ceramics in a variety of ways. Regional workshops provided artists with skilled craftsmen and technicians who supported their experiments in a new medium. Work in ceramic was shown by a number of galleries as early as the 1930s; it was regularly included in fine art exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale and written about in publications such as Domus. Following World War II, a number of galleries and exhibitions were entirely devoted to ceramics, and ceramic murals were commissioned for decoration of the exterior and interiors of architecture. Among the better-known artists whose work the book illustrates, are the sculptors Marino Marini, Fausto Melotti , Arturo Martini, and Leoncillo Leonardi (all of whose sculpture was in clay) and the sculptor and painter, Lucio Fontana; it also includes work entirely in a ceramic tradition by Giuseppe Civitelli, Marcello Fantoni, Guido Gambone and Pietro Melandri.

One striking aspect of the work is the extent to which artists used ceramics in conscious reference to artworks in other media; the Italians obviously put no emphasis on a separate sphere for ceramics, with an aesthetic entirely rooted in the medium. Guido Gambone painted a vase with a design that clearly derived from Picasso’s Guernica; a vase by Lucio Fontana is decorated with the heads of three horses that refer to the Parthenon friezes; Piero Melandri based the form of a vase on those depicted by Giorgio Morandi; and Fausto Melotti based the craggy formlessness of Omaggio a Lucio Fontana on a sculpture that Fontana had exhibited the previous year.

This book will be welcomed by readers interested in Italian modernism as well as followers of ceramics, and reveals a fascinating and little-known area where the distinction between fine and decorative arts was truly dissolved.