British film director Peter Greenaway interpreting Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper seemed a compelling combination. At least it piqued my curiosity. While the exhibited video work concluded its run at The Armory in NYC on January 6, I have been struggling to find the words to describe my disappointment and dissatisfaction (to put it lightly) ever since the work confronted me. While some of its technical setup and execution are to be praised, the finished product betrays and insults the experience of Da Vinci and his masterpiece. I write this piece because Greenaway intends to continue exploring some of the world’s greatest masterpieces, transforming them into multimedia experiences.

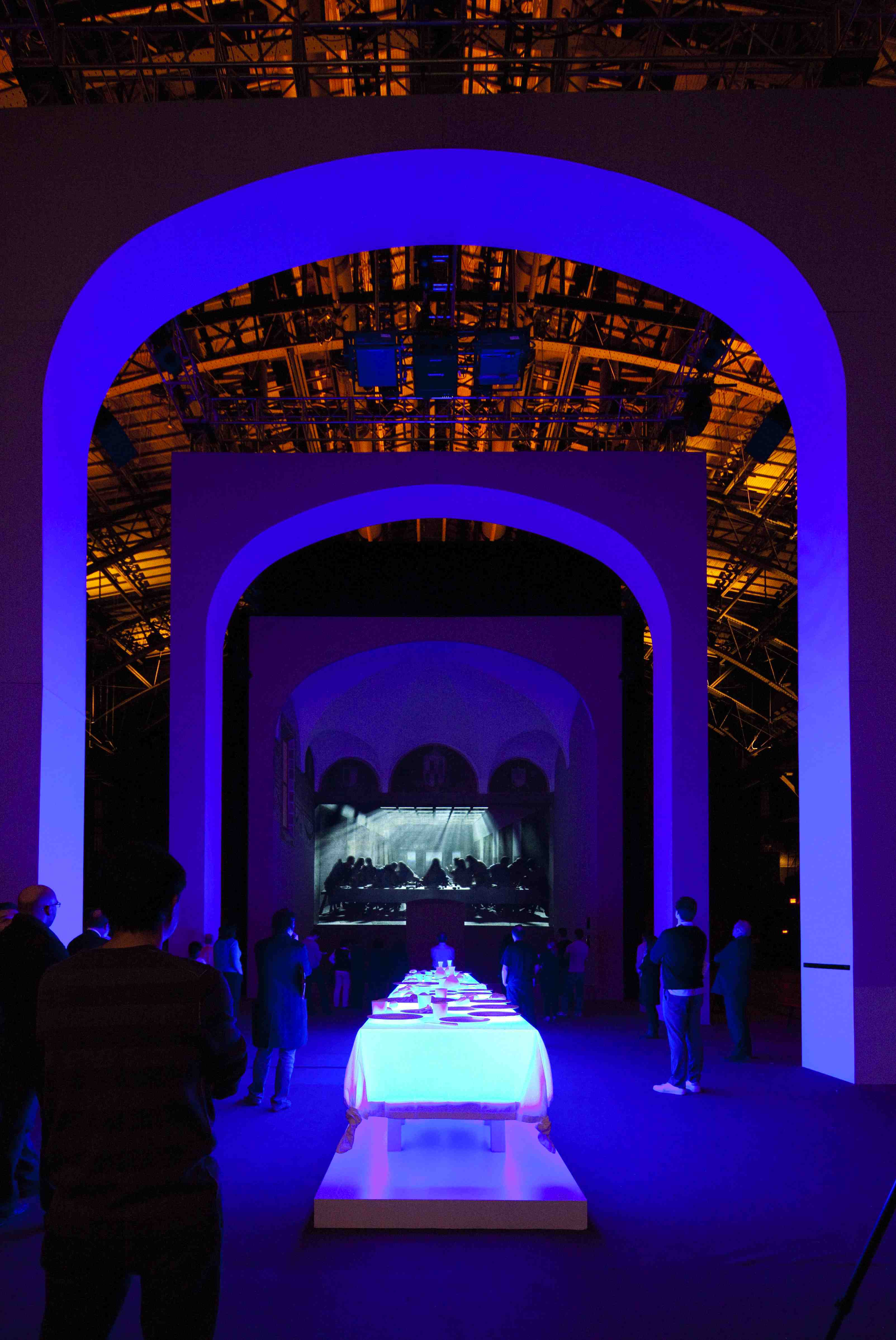

But first to critique the current work. Set in the Armory’s glorious main hall, Leonardo’s Last Supper: A Vision by Peter Greenaway consisted of three parts in two spaces. The prologue, Italy of the Cities, felt like a whirlwind tour through the history and geography of the Mediterranean country. I felt as if I had been swallowed by a high-speed digital wormhole, as I was bombarded on all sides (screens behind screens, screens on four sides of the room, on the floor, hanging from the center of the room…) by blueprints, photographs, swirling light, and architecture – all ‘celebrating’ the genius of the Italians. I put celebrating in quotations since the barrage of images, without any narration, was far from, in my opinion, worthy thoughtful praise for the great achievements of Italians.

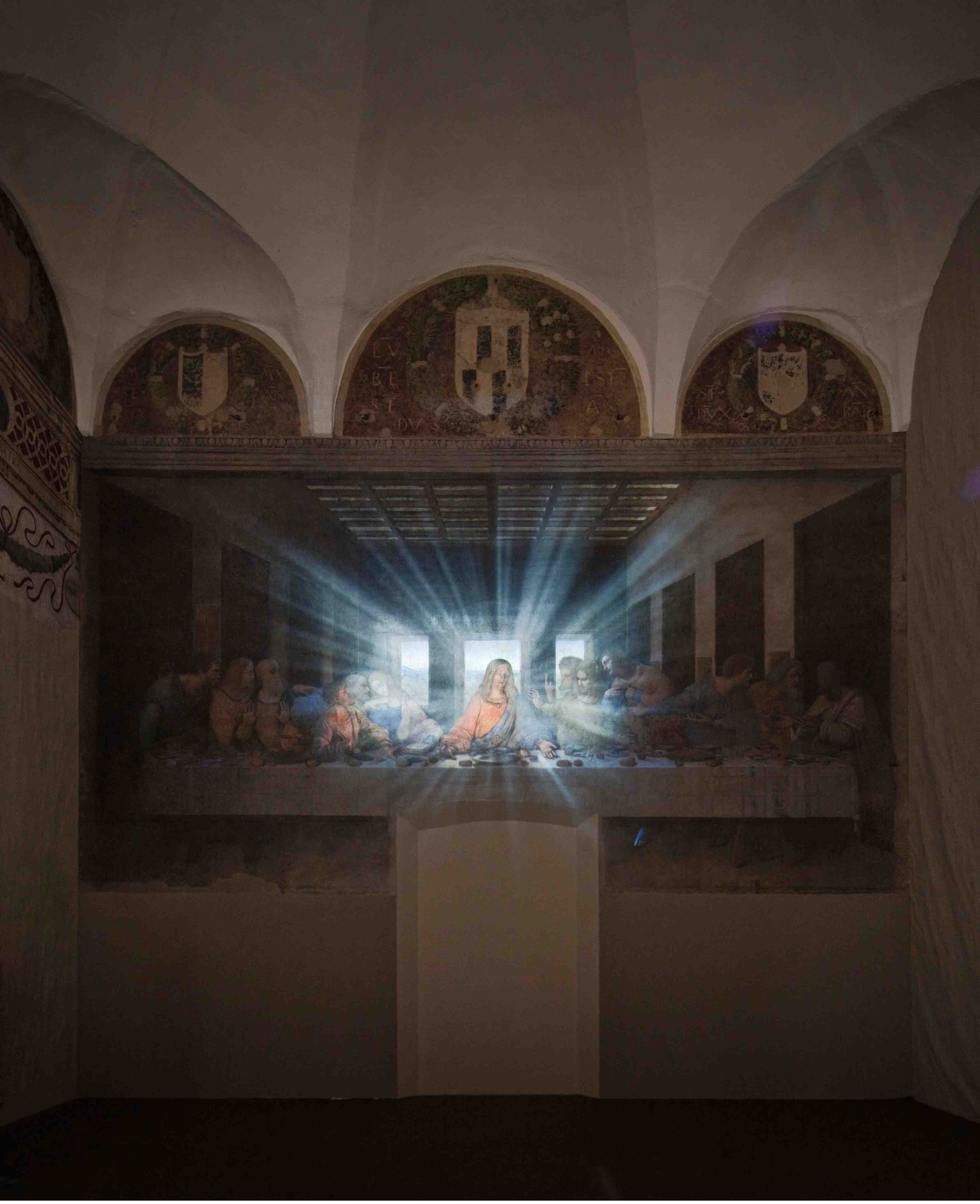

At the conclusion of the prologue, doors opened to a space replicating that of the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery. A clone of Da Vinci’s mural was also beautifully reproduced in the space along with a translucent life-size sculpture of the last supper table which changed colour during the twice-played video loop (excerpted here). During the duration of the piece, The Last Supper went from being a static image to being manipulated to: change the light conditions in the painted space, give Jesus a halo and divine glow, as well as to highlight the trios of figures, hands, and the weapon of betrayal. The colours shifted and, at a certain point, blood ran down the table. At this point I wanted to leave. I was just waiting for the figures to become animated, half-expecting it would happen. Without narration, it was implied that all these highlights and effects could all speak for themselves (when in fact they were but juxtaposed fragments). Meanwhile, back in the screens of the first space, still visible, footage meandered across microscopic close-ups of the mural’s paints and pigments.

I have seen The Last Supper in Milan and it is an auspicious experience to be in front of such a fragile and masterful painting that has survived its tumultuous history. Its beauty is trying to absorb the fullness, the reverence, the fragility of the painting. Adding a light show and computer effects (while top-notch and displaying excellent skill) ruins the work for me. Or rather, the way they were added ruined it. Taking on Da Vinci as well as taking on a quintessential scene from Christian theology were perhaps too ambitious. In any case, the final product lacks a clear voice and comes off as blasphemous and sacrilegious (both to the Christian religion and those, like me, who are devoted to the religion of art). Greenaway’s ‘vision’ ruined an original masterpiece.

The last part of the flashy and slightly crass show was slightly redeeming, as it featured a narration that took time to explain the imagery depicted in Veronese’s Wedding at Cana. While informative (spruced up with fancy overlaid simple graphics) it did initially come off as a bit dry and art historical. The addition of voice-overs changed that impression, and this last segment ended with simulated rain and fire in the painted scene, a conclusion that left me non-plussed with Greenaway’s production.

Yet Greenaway has done this before, and intends to do this again. The British director intends, with his project Ten Classic Paintings Revisited, to bring together art and film, and inspire viewers to really engage with great works. At a time when the average visitor goes through a museum like a shopper at a supermarket, checking items off a list, I find the intention commendable. But is the execution worthy? Watching a preview of his previous project exploring Rembrandt’s Nightwatch, I was impressed to see a more in-depth exploration of law and justice in 17th-century Netherlands, complete with actors and re-enactments.

With The Last Supper and Wedding at Cana, the dissonance between the static masterpiece and the urge to bring it into a more dynamic medium is nothing short of loud and uncomfortable. The project may have been too ambitious in its choice of artwork and subject matter. Greenaway intends to continue his project and work with Raphael’s Wedding of the Virgin, Picasso’s Guernica, Velasquez’s Las Meninas, Monet’s Water Lilies, Seurat’s La Grande Jatte, Pollock’s One: Number 31, and Michelangelo’s Last Judgment from the Sistine Chapel. An ambitious project. Unfortunately, this time around, I believe Greenaway did not properly command the visual exploration in order to deliver a thoughtful message. I only hope that his next attempts are more considered. I just know that I won’t be hastening to see the next Greenaway production with the optimistic curiosity I had this time around.