By Daniel Forrest Hoffman

The beauty of a city, a building, or a home has often been explored through natural signs of age. The “lived in” quality of a place is usually what allows it to speak about itself and its history. Erin Murray’s solo exhibition “Architecture Parlante” at Slingluff Gallery (through Feb 27) explores the subject of architecture and the way it describes its function and/or identity from a different perspective. The structures in her oil paintings and drawings are idealized and nostalgic. They are stripped of any sign of wear, yet they reference a history. Her images are soft and detailed, familiar yet alien. Landscapes are devoid of human figures, and in their absence, the structures become the major players, describing themselves, not through signs of having been lived in, but through individualizing adornments and signs. Murray celebrates the mundane by carefully rendering details of aluminum awnings and unique brickwork.

The materiality of the work is striking. In Learning From Harbison Avenue her drawing embraces the fibrous cotton paper to create beautiful dark velvet stretches of sky coupled with meticulous architectural detail. It is easy to be seduced by the beauty of the images and skill of the artist’s hand. Murray uses this to persuade the viewer to find beauty in such ordinary settings as a Northeast Philadelphia block of rowhomes, and in fact they are quite beautiful.

At first the eerie lack of figures and odd angles feel ominous and alien, like a De Chirico painting minus the surrealist symbolism. However the character of the structures quickly fills that emptiness. Each rowhome, nestled next to its neighbor is like a figure. They are individualized with adornments like wrought iron fences or aluminum awnings. Despite this, the structures are quite inhuman. They feel sterile in a way that denies the humanity that allowed them to exist in the first place. What is striking though is the lack of wear and age. At times, the image feels like looking at an old black and white photo of your grandparents when they were young. It is nostalgic, yet somewhat unfamiliar and foreign. In today’s climate the work feels quite poignant, as it seems to call into question where the people are in this scene? Where is there a role for the people at the socio-economic level that would occupy these homes? In fact it is the structure that is timeless and the events of our day and the people who play parts in them that are fleeting.

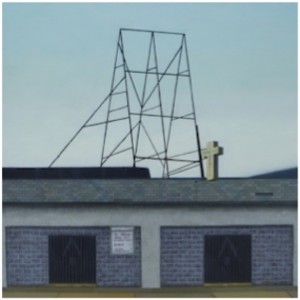

This nostalgic, unfamiliar feel continues in Murray’s paintings, most of which set up a scenario where a building sits all alone in a landscape or against a cloudless sky. In Yokefellow the building desperately tries to get out the message of its function as a religious meeting place. However the massive empty billboard structure that sits atop it competes for attention and soars into the sky. It becomes a monolithic monument to empty thought and advertising.

BBillboard is a similar composition. Here Murray depicts a piece of architecture that seems to come out of a suburban strip-mall nightmare. Buildings like that have little to say and Murray comments on this by depicting the graffiti on the back. The tags on the rear of the building are more interesting to look at than the intentional architecture of the building.

In this exhibit I find the drawing the most compelling, as it is so open and honest. It does not seem to make a point, as do some of the paintings in the show. It simply presents us with a setting to absorb. As the poet Archibald MacLeish said “A poem should not mean, but be.” In this work Murray does not need to make the work mean anything, as it simply is the embodiment of her ideas. The homes are lonely despite being nestled next to one another. The composition is full of emptiness. It seems to capture a general mood that has pervaded our culture during the past year while this work was being made.