Bohyun Yoon has been taking photographs of the people of Philadelphia . One of them turned out to be my friend Wendy, who was out in Rittenhouse Square walking her standard poodle Nelly when Bo approached. She talked, he talked, and they found out they had me in common. Wendy’s face is now one of the nearly 150 faces that make up Bo’s newest installation–150 different faces that have nothing–and everything–in common.

The new installation, in Bo’s Crane Arts Center studio, seems simple–a large cube framework nearly filling the space, from which hang the portraits–each silk-screened onto a glass plate in a different monotone color. A single bare bulb, hanging in the center of the cube, projects the portraits onto the wall in gray scale, creating a catalog of faces and souls. Very Christian Boltanski. But Bo’s spirits also have the liveliness of newsprint and community. Wherever I stood, I was crowded in among the nearly 300 faces pressing in from the colorful glass plates and the shadowy projections. Bo said my friend Wendy was in the crowd, but he couldn’t find her just then.

Then Bo, who teaches at Tyler School of Art in the glass department, started talking–about neighborhood, the South Korean army, life, death, and race.

Libby: What are you thinking about when you make these portraits?

Bo: They are like neighbors. When I first came to Philadelphia, I was surprised to see so many different races. Korea is (more homogeneous). I am now in Northern Liberties. The neighborhood is changing, not as mixed. But we are all the same human beings, have the same soul. There’s life and death–that’s for everybody. …I am interested in light and shadow. …I want to reveal something behind–life and death. If there’s death in it, I can feel the beauty. Beauty, art, needs to have death in it.

Libby: Do you have any shows coming up?

Bo: The Smithsonian Museum in 2012 asked me to show my helmet, a glass instrument, in a show “40 under 40.”

My education was in glass as a craft material. But glass art is always set up on a pedestal. It’s very precious. I don’t like that. I asked myself, How can I see this material from a different perspective. How about I wear the glass. …I have to move my body to make a sound. Body and clothing mean lots of things. Uniforms carry identity in society. And the military is a controlled society and has a controlled uniform.

I feel human beings are such a fragile and weak creature (in a system of societal rules). We are like puppets controlled by some invisible power. We are tricked by power. The doll (in Shadows) is truncated like a puppet, and is flipping reality and unreality. This (new installation) is a similar setup. Society and politics–(they are) for human beings and life. In the afterlife, there is no race. I don’t know what that world is. I want to see our life (from) a little bit of distance. We complain about politics and rules. But we are small creatures, born and living with other people.

Libby: Why did you leave Korea?

Bo: I felt I have a little bit of talent. I was thinking (about what) I live for, what I am meant to be. And I want to help people somehow, but using this talent, art, so something is revealed, something a little hidden.

I came here in 2001. I started RISD, and had good freedom, and passion about art. After, I go back to join the military. Korea wouldn’t give me the passport extension. (All South Korean males must serve two years in the military). During that time (in the military) I was not able to make art.

I did not want to go. My father and other people said, if you look at two years from (today), it feels long, but in a whole life, two years is not long–and it’s a special experience. But two years in the army is quite long. (Bo said when he was a child, he loved toy guns, but the realities of guns in the army–the weight, the harsh recoil, the loud bang, and the smell of cordite–was terrible).

Libby: Did you have to fight?

Bo: I did graphic design at a computer. I was a translator–I also speak Japanese (and English).

Then RISD invited me to come back to teach, under a changed visa type.

Libby: And now you’re teaching at Tyler?

Bo: Yes, in the glass department.

Libby: How do your parents feel about your being an artist?

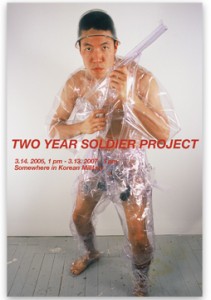

Bo. My parents are happy with what I’m doing. My father is a business man. I really appreciate that he understands me. I always watch him wearing a suit all the time. At RISD I was wearing casual clothing. The clothing is wearing us, not we them. The clothes are controlling you and you not them. I made a transparent business suit and walked in Rhode Island with a vinyl suitcase. I appreciate that my father, my parents, understand me. I made camouflage, vinyl, and a soldier’s glass helmet and gun (in my Two-Year Soldier Project). I made a postcard of me. I made it before joining the army.

Libby: Do you plan to stay here?

Bo: I want to stay in the United States. I am interested in contemporary art. There are many different artists here with brilliant ideas. But I’m thinking I don’t know really about my country. I have to learn and study about my country. I like Koreans. They speak their mind. Koreans on the outside are very aggressive; many people compare them to Spanish people. Koreans are loud but are making good relations (i.e. get along with each other).

I also lived in Japan. There people are the opposite. Outside they are very quiet and protect themselves. Koreans are fighting but have good connections with each other.

Libby: When did you fit in living in Japan? How old are you?

Bo: 36. I was born in 1975, December, but my documents say 1976, February. My father went to register me late, not right away. It’s not that easy to change. I tried. …

I lived in Japan 10 years. I was an elementary school student. My father is a banker. The bank sent him to their Japanese branch.

My mother is a ceramist. When I said I was going to study art, she said ceramics is kind of old. Why don’t you do glass? At that time there was no glass education in Korean universities, so I did my undergraduate and graduate education in Japan, in Tokyo. Then then in the US at RISD did an MFA again. Japanese education is very craft-wise, and I was curious about contemporary art. But the craft background is helping.

Libby: What’s next?

Bo: A baby. My wife (artist WonJung Choi) is pregnant, in her last trimester.

On my way out, I spotted Wendy’s face.