Stargazers; Elizabeth Catlett in Conversation with 21 Contemporary Artists, on view at the Bronx Museum of Art through May 29, 2011, exhibits forty of Catlett’s sculptures and graphic works juxtaposed with work by two younger generations of artists who share her concerns with the roles and images of African-Americans, particularly African-American women, and with broader questions of social (in)justice. Catlett is a major figure whose work is referenced more often than seen, and unless you caught the retrospective that toured in 1998 you’ve not likely seen this much of her work. She is also a living connection with seventy years’ of American and Mexican art history, and remarkably, is still active at ninety-seven.

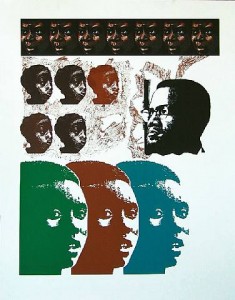

Catlett’s work has been overwhelmingly figural, although she acknowledges that her sculpture has been more concerned with purely formal issues than her prints, and she has occasionally ventured into sculptural abstraction. She looked to West African art for its formal manipulation of the human figure, and like Wifredo Lam, claimed African art as part of her patrimony at a time when European and American artists were appropriating African forms as a romantic primitivism. Her prints show tremendous virtuosity and graphic punch. While her best known prints are woodcuts in the manner of 1930s social realism, several prints from the early seventies were unexpectedly powerful, incorporating the style of Pop art and 60s posters, and mixing hand-drawn images with those taken from photographs of figures of Black resistance, such as Angela Davis and Malxolm X.

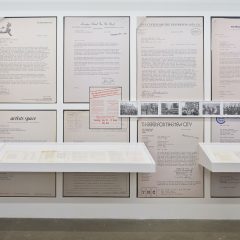

Catlett has worked to her own standards, even as the art world turned its back on her frankly-populist stance. She continues to produce work with a message of respect and affirmation for the lives of the working class and of African Americans marginalized by American culture. She worked for the Federal Art Project of the WPA (Works Progress Administration) and was among a group of artists involved in left-wing politics who created art for social change. In 1946 she moved to Mexico where she was involved with the Taller de Gráfica Popular, which produced popular prints in the service of social and political goals; she married a Mexican artist and remained there.

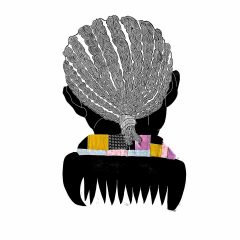

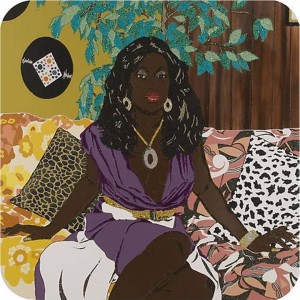

Some of the younger artists have acknowledged Catlett’s influence, others were chosen by the curator, Isolde Brielmeier, presumably because of shared social concerns. What’s most striking, however, is the distance most of them take from Catlett’s populism. Their work is sophisticated, knowing, multi-leveled, sometimes camp and largely ironic. It’s hard to know what an audience outside the art world would make of it: Hank Willis Thomas’ golden pendant of a bound slave as a take-off on urban street jewelry; Kalup Linzy’s send-up of soap operas in intentionally-unconvincing drag; Mickalene Thomas’ sequined and seductive femmes; Sam Durant’s abject, broken mannekin, Female Indian (nude); Wardell Milan’s trash pile of commercial detritus in the midst of urban decay, with the caustic title, One could still dream to devise an optimistic antidote against the defeatist and cynical claims.

A few of the younger artists do convey some of Catlett’s un-embarrassed celebration of the dignity of ordinary people: Robert Pruitt’s pastel drawing of a young girl in a tee-shirt that reads “Negro es bello”; Carrie Mae Weems’ mother and daughter negotiating a homework assignment (although as part of a series, the photographs were accompanied by texts that complicated the domestic scene); Xaviera Simmons’ family portraits; and Patricia Coffee’s hauntingly-beautiful, improbably black girl in a pink dress. Coffee, in fact, captures some of the beauty of black skin that Catlett renders so remarkably in her lithographs.

The exhibition comes off as a meditation on Catlett’s affirmative imagery, intended to effect real change (if only at the personal level), in contrast to art that acknowledges the inherent politics of all imagery but has little faith in its efficacy at street level. It raises interesting questions about art which professes an interest in progressive politics, yet distrusts imagery targeted at the masses; an art that speaks in a visual language far from the vernacular. And to whom?

On April 29 at 6pm Catlett will participate in a panel discussion with Sanford Biggers, Renee Cox and Xaviera Simmons.