[Ed note: I asked poet and Penn Writing Fellow Thomas Devaney if we could reprint his catalog essay for Sarah McEneaney’s current solo show at Tibor De Nagy Gallery in New York. (The show’s up now through June 2.) Devaney and McEneaney graciously agreed to let us post the essay. See the gallery’s website and McEneaney’s page on missioncreep for more images. See our index for more artblog posts on McEneaney.]

SARAH MCENEANEY: RECENT HISTORY

By Thomas Devaney

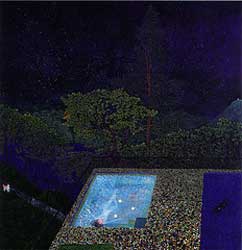

Watsonville (2005)

You don’t so much control as work with your materials, which inevitably include yourself, whatever may be your most intimate facts.

—Bill Berkson from “Working with Joe”

Looking at the paintings of Sarah McEneaney, one is struck by the intimacy of her panoramic views. Taking McEneaney’s everyday surroundings as her subject matter is one thing. But these are remarkable figurative paintings, which display a convincing and nuanced marriage of a person and paint. Yes, there are the accumulated moments and charted events of Sarah’s recent history: her cancer; the death of her dog Birdy; her work in the studio; the construction and build-up of Tresletown, her industrial neighborhood in Philadelphia’s Chinatown north. But it is the painterly attention she pays to her subject matter and her singular treatment of it that is most captivating. The interplay of subject matter, scale, and exacting egg tempera paint is simply marvelous.

In the painting RB Fisher, 2005, (not shown), your eyes address a tiny figure (Sarah) working in a spare, seemingly white, studio; they drift up to the large window opening out onto the summertime trees, then rise even further to the sloping pink and white wood ceiling and return to the wide-angled green floor area, only to encounter five or six miniature paintings in progress on the studio walls, along with a dog, a table, and a few other chairs scattered just so throughout the space.

Good and Plenty, 2002, egg tempera on clayboard,10 x 8 inches

Many of McEneaney’s paintings have a light, deep, and fresh beauty. She simultaneously strives for an opaqueness that calls attention to the color-infused nature of the work, and for a transparency and overpainting that highlights the engrossing abstract aspects of the paintings. She comments, “Everything means something, every inch.” Notice the translucent cloth of the otherwise nondescript window shades, the play of light in her glass-block doorways, the swirl of warm bathwater, and her unbelievable skies, ceilings, and walls of every degree and configuration. Close up, you can get lost in the infinitesimal attention of her brushstrokes; from a distance, you glide, attempting to take in the larger scenes.

In painting after painting McEneaney seems either to bring more light into the world, or to make us more aware of the light that is there. Her works include studio scenes (paintings within the paintings), Sarah sleeping under windows or daydreaming on day beds, and an art historical nod in Recent History (2006), which dramatizes and wryly plays with the intimate and the panoramic at once.

Recent History, 2006, egg tempera on wood, 17 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches

Here, at the threshold of her studio, Sarah hoists up a curtain inviting us into her living museum. The painting aptly echoes Charles Wilson Peale’s defining work The Artist in his Museum (1822). Sarah’s painting displays her own curiosities. At first glance it appears to be a series of abstract paintings, but looking more closely, we see depictions of healthy and bad cell structures; a body undergoing a CAT scan; and a scroll-like calendar containing the tiniest hand-written appointments and dates.

McEneaney’s work also includes traces of Henri Rousseau, Frida Kahlo, and Alice Neel, as well as hints of Indian, Medieval, and Early Renaissance painting. The most significant comparison, however, might be with the exquisite world and work of Florine Stettheimer from the mid-teens throughout the 1920s and ‘30s. Though McEneaney’s paintings are not exquisite in the same manner as Stettheimer’s, they share key sympathies.

My Lucky Garden, 2006, egg tempera on wood, 27 1/4 x 36 inches

Most notably, their often-panoramic work reveals the ways in which their lives are distilled into their private and idiosyncratic art. Each painter is also her own original stylist, absorbing various aspects of American folk art as well as Persian miniature painting. Some of the differences include the distinct atmospheres they both create and inhabit: Stettheimer’s arch urbanity, populated with the denizens of Modernism, contrasted with McEneaney’s contemporary life as an intrepid, private urban dweller. Ultimately, McEneaney and Stettheimer are kindred souls. Each painter, in her own time and place, is unique, and both give the kind of stimulating visual pleasure we receive from the greatest art. They are both independent artists making the paintings they want to make, in their own way.

It is worth saying a few words about McEneaney’s recent painting Watsonville, 2005 (see top image). The painting depicts an enormous nighttime sky surrounded by a dazzling light-bright patio, and a luminous pool in which Sarah is swimming. Out beyond the pool is the wood-lined property and above is the (literally) brilliant sky, all of which is considered from Sarah’s intimist point of view. Because of the prominent placement of the radiant pool of light in the foreground, the darker side patio on the right, the dogs off to the left (down upon the edge of a blackened green hill), and the woods and great sky above, each section of Watsonville offers its own ruminating world. It is like looking at several paintings at once where the parts and the whole simultaneously cohere.

In her biography Willard Gibbs: American Genius (1942), on the noted physicist and inventor of vector analysis, Muriel Rukeyser famously observed, “the world is made of stories, not of atoms.” Reflecting upon McEneaney’s captivating paintings we may slightly expand Rukeyser’s aphorism to say: the world is made of stories and paint, not of atoms. Or, to go a step further, our world, as seen through McEneaney’s prism, is made up of stories, paint, and atoms all together.

–Thomas Devaney is a poet and author of The American Pragmatist Fell in Love (Banshee Press, 1999) and Letters to Ernesto Neto (Germ Folios, 2005). His collection of poems Incessant Spaces is forthcoming from Fish Drum Press. He is a Penn Senior Writing Fellow in the English Department at the University of Pennsylvania.