Today’s your last chance to do a truly civic feel-good thing–bid in a silent auction on a photo or print to help support the Free Library’s Prints and Pictures Collection.

The collection is an amazing thing, something you can visit both in the library, and in cyberspace. And people who cherish it formed the Friends of PIX to help maintain it, and they are behind the auction. So hurry up and go bid and buy and you can figure you’ve done your good deed for the week!!!

Today is also the last day of this year’s PIX art show–Documentary PIX: Philadelphia, A Century of Change. Prints and Pictures puts on a show, talk and fundraiser each year to not only raise money but to honor the late Robert F. Looney, the collection’s curator from 1963 to 1986. I went to the opening event at the Free Library about a month ago to both see the show and hear the panel discussion on my favorite photo question, what’s real?

The panelists were eminent photo critic A.D. Coleman; independent arts writer Nancy Brokaw; and documentary photographer Daniel Traub. Many of the main themes each presenter talked about during the panel discussion were crystallized in the Q&A afterwards.

Someone in the audience was worried about reliability of documentary work in the age of PhotoShop. A.D. Coleman, who was the first photo critic at the New York Times, said he didn’t think PhotoShop was making that much of a difference. “We have photos from the Civil War that were changed,” said Coleman. “On some level, the power of documentary has always depended on the photographer saying to us, I saw this, this happened. Goya wrote this on some of his Disasters of War–‘I saw this.'”

Nancy Brokaw, who teaches at the University of the Arts, agreed: “It’s always been an interpretation. …Anything that purports to be a document is always a flawed document. It has just gotten to be easier to do.”

And documentary photography Daniel Traub said it’s all a matter of degree vis a vis the changes that you make with PhotoShop. It’s the difference between adjusting the color and putting something in or taking something out. “You need to have clarity about what you are doing.” He cited photographer Edgar Martins, who denied his manipulations of photos that ran in the New York Times, as an example of what not to do. Embarrassment all around.

(Traub during the panel discussion had also talked about how the process of taking photographs helps him figure out what feels real to himself. It took him several years in China before he figured out that the theme of self-reinvention was an important factor in his photographic choices in a country that has thrown out its history of language and culture.)

Pixel manipulation is only one of the ways a lie can be created in photography. Coleman cited Robert Doisneau‘s kiss in front of the Hotel De Ville, which stood for a half a century as a wonderful picture of romance in Paris. Then the truth came out. It was staged, with two paid actors feigning a kiss. “He didn’t change a pixel, didn’t change a silver particle. It’s the identical physical thing. But the response that I have to it has changed completely. It has gone from sociology to theater. I now have to suspend my disbelief, which is what I do with theater.”

In answer to a question about beauty in Picasso’s Guernica still successfully communicating war, Brokaw said, “You don’t want to make ugly pictures. …If you take beautiful pictures of a disaster and that’s where you stop [at the beauty, with no intent of fixing a wrong], you’re in some decadent space where I don’t want to live.”

Coleman chimed in on Brokaw’s point by paraphrasing a Pablo Neruda poem on the effect of bombing during the Spanish Civil War: “The blood of the children on the street was like the blood of the children in the streets. …Sometimes you need to restrain the poetics in order to let the brute facts speak for themselves. Sometimes you need to enhance things to get it across.”

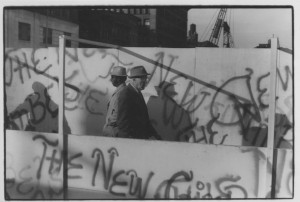

After the discussion, most of the audience wandered out for a meal and a look at the exhibit, which features documentary photography from the Free Library collection of Philadelphia–images from the turn of the 20th century, images from the 1950s, and then images from today (more or less) by 15 contemporary documentary photographers.

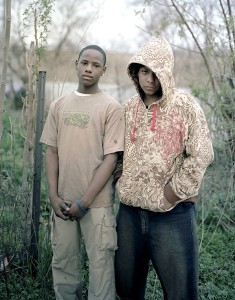

Curated by Drexel photography Professor Blaise Tobia and Photo Review Editor Stephen Perloff, the exhibit captures the civic pride and optimism embodied in the photos of the previous century, such as Frank Taylor’s bird’s-eye-view of the city from the Bell Telephone Building, or the photos of building the Schuylkill Expressway and the Oxford Circle area. The unblinking, often unsentimental work of the last decade stands in sharp contrast, from Harvey Finkle’s sympathetic photo of a welfare-cuts protest to Sandy Sorlien’s vines overgrowing the decrepit Eastern State Penitentiary to Zoe Strauss’ portraits of people living on the edge.

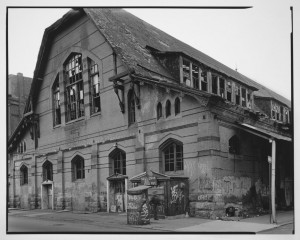

My favorite grouping in the show was a pair of pictures by Joseph Labolito opposite a photo by Karen Lightner.

Lightner, who for many years was curator of the Prints and PIctures collection at the Free Library, had commissioned Labolito to take pictures documenting Philadelphia for the collection. His two photos of the Youth Study Center’s womens (pink) floor and mens (blue) floor capture the dehumanizing architecture of the building before it came down. The baby sex-coded colors were almost surreal. Lightner’s more recent picture of the partially destroyed building also catches the pink and blue floors. What a pairing–and kudos to the curators for this!

Other contemporary artists in the show are: Jim Abbott, Noah Addis, Michael Bucher, John Dowell, Jr., Daniel Lobdell, Zoe Strauss, and John Woodin. You can see many of the images on line here.

Oh yes, and don’t forget to be a citizen and put in a bid.