It’s hard to imagine another exhibition that would be of equal interest to members of the AIA (Archaeological Institute of America) and the NRA (National Rifle Association), to subscribers of Hali (the leading publication in the world for carpets, textiles and Islamic art) and readers of Soldier of Fortune (the mercenaries’ monthly). Battleground: War Rugs from Afghanistan at the Penn Museum through July 31, 2011 is the first stop on a U.S. tour organized by the Textile Museum of Canada, Toronto; it is likely to amaze most viewers and will fascinate anyone curious about the world, the impact of war upon civilians, international visual culture, the flexibility of women artisans and the place of traditional crafts in the Twenty-first Century. It shows the extraordinary products of the merger between ancient tribal craft and the most advanced of technological equipment: computers, fighter jets, armed tanks, as well as the somewhat more old fashioned tools of war: Kalashnikov automatic rifles, hand grenades and land mines.

I was totally intrigued with Afghan war rugs (sometimes referred to as Kalishnikov carpets) when I saw them several years ago at the Troppen Museum in Amsterdam, but they have been little exhibited in the U.S. This is a chance not to be missed. The tradition of tribal rugs in Afghanistan derives from the central Asian Turkmen and Baloch tribes, and only attracted Western attention in the late 19th century. Afghanistan has been a continuous battleground since 1979 when the Soviets invaded, and one consequence is the largest community of exiles in the world (6.2 million in 1990), living primarily in Pakistan and Iran where peoples from all over Afghanistan mix. Some time in the 1980s, Afghan rugs began to appear with new motifs: the instruments of war. Their origins are uncertain because of the extensive mixing of exiles and the many hands through which the rugs pass before reaching the West.

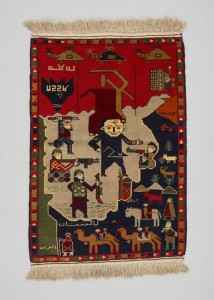

The intended audience for the rugs is equally uncertain. Prof. Brian Spooner, curator of Near Eastern Ethnology at the Penn Museum and a specialist in Afghan rug weaving, suggests that the earliest war rugs were designed for Soviet tourists, and after 2001, for the U.S. military. This does not explain the designs, several of which are on view, that celebrate the Soviet withdrawal and also picture Afghanis fleeing the country by foot and on camels, followed by women bearing goods on their heads (see the rug depicting Najibullah, below). Spooner describes the war rugs as an effort to respond to an international market and quotes a local dealer that men provide designs for the rugs, which are mostly woven by women.

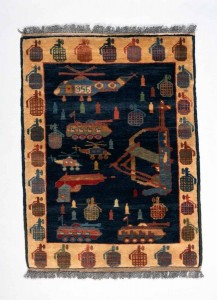

The rugs are all based on traditional, tribal formats, and in some cases the modern weaponry is worked into the pattern so subtly that it is easily overlooked on first viewing. Some of the decorative borders incorporate bullets, grenades (above), armored vehicles or war planes. Or the central field, which often represented a garden on traditional rugs (the garden itself likely referred to heaven) is given over to guns and tanks, helicopters and bomber jets, all distributed in the patterns of traditional designs. In one group of rugs, two large Kalashnikov rifles face each other on either side of the carpet, forming symmetrical borders that at first appear to be abstract decoration. The weapons and planes are shown with enough detail to distinguish a Soviet Kalashnikov from a U.S. M16.

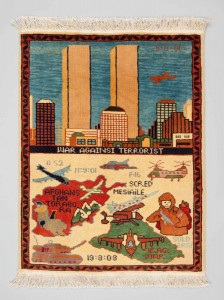

The exhibition divides the rugs according to general type: one group depicts maps of Afghanistan, occasionally its bordering states or areas beyond; another group commemorates Afghan heros (above); some show modern cities in Afghanistan (such as an aerial view of Kabul, with a border of helicopters that accurately reflects the city’s regular aerial surveillance); a few depict the twin towers of the World Trade Center (below). The most gruesome rugs show adults and children who have lost limbs to land mines; the most common mines are butterfly-shaped and are sometimes represented abstractly, at other times by images of actual butterflies.

A handful of the rugs on view incorporate more than Western motifs, employing Western visual conventions of perspective as well, and one particularly striking example employs the multiple parallel images of much international television news, complete with texts running along the bottom. Despite the many unanswered questions about these war rugs, they unquestionably testify to the state of war as an ongoing feature of Afghan life, to the persistence of tribal craft traditions, the flexibility of craftsmen who produce goods for trade and the role of trade in intercultural contacts; most of all, they reflect a population of uneducated women who can produce such labor-intensive products for such low prices. When universal education becomes standard in Afghan communities, it may be the end of the production of hand-made rugs. But the women will certainly celebrate the beating of tanks into tractors and guns into pruning hooks, when, as Issiah foretold, nation will not take up arms against nation, neither will they train for war anymore.