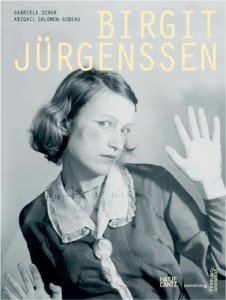

It’s welcome to see increasing numbers of serious books on women artists, even if all three discussed here are posthumous. The volumes on Spero and Wilke pay sustained attention to two Americans who are well-known and widely reproduced; the book on the Austrian, Birgit Jürgenssen (1949-2003), is an introduction to a fascinating artist whose work is all but unknown in the U.S.

Gabriele Schor and Abigail Solomon-Godeau Birgit Jürgenssen (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz and Vienna: Sammlung Verbund, 2009) ISBN 978-3-7757–2461-6 (English edition)

Birgit Jürgenssen’s education, teaching career and exhibitions took place primarily in the very small and in-bred art community of post-WWII Vienna. She created drawings, photoworks and objects exploring the social and personal construction of the feminine, and particularly woman’s body — often costumed, bound or distorted, sometimes in fragmentary form or as an icon, and often using herself as subject. It is an extraordinarily intelligent, imaginative and compelling body of work that deserves to be more widely known.

This book, the first on Jürgenssen in English, is extensively illustrated with more than 350 full-color images and articles by five scholars, as well as a list of the artist’s exhibitions and bibliography. Gabriele Schor looks at Jürgenssen’s evolving ideas about identity throughout her career, situating the artist on the threshold between modernism and post-modernism. Jürgenssen’s use of self-irony as a necessary tactic in her construction of self is the subject of Elizabeth Bronfen.

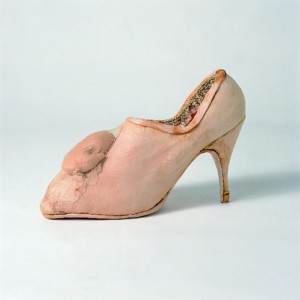

The first of Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s pieces looks at femininity, sexuality, gender, and subjectivity as problems of representation that are the chosen terrain of Jürgenssen’s art, analyzing the drawings and the photoworks, which she characterizes as a form of performance minus the audience. The second of Solomon-Godeau’s articles focuses on the Shoeworks and Jürgenssen’s unveiling of what fetishism seeks to repress. Two further articles examine specific subjects which Jürgenssen explored in series: Sigrid Schade on the Dance of Death photographs (1979-80) within the European tradition of the subject, and Geraldine Spiekermann on Jürgenssen’s use of water in various photographic works.

It is significant that, despite the fact that most of Jürgenssen’s oeuvre involved her own body and the suggestion of psycho-drama, the authors avoid discussion of biography other than her artistic training, practice and exhibitions. While this is a corrective to the tendency to frame women in terms of their personal lives, the catalog unfortunately omits situating the artist within art in Vienna from the 1970s to the turn of the twenty-first century, or discussing any feminist activity with which she might have been involved (with the single exception of her involvement with a group, DIE DAMEN, which is mentioned but not explored). To the outside world, Vienna of this period is associated only with the work of the Actionists (an entirely male group) and with Valie Export. Only recently has widespread attention been given to Maria Lassnig, a painter of an earlier generation than Jürgenssen and still active; Jürgenssen taught under Lassnig’s direction at the School of Applied Arts. Still, this is an important exploration of an under-known artist and will be of interest to students of European art of the late Twentieth Century and to anyone interested in international feminism.

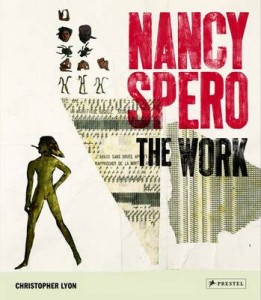

Christopher Lyon Nancy Spero; the work (Munich: Prestel, 2010) ISBN 2010930006

Lyon was a friend of the artist, who invited him to write a critical survey of her work, made her archives available, and had numerous conversations with him over many years. The result in no way reads like an authorized biography where the writer tiptoed around difficult aspects of his subject. Lyon has produced a monograph that amply rewards her trust, placing her work firmly within the history of the art of her time, her extensive research (in history, literature, and art, particularly Neolithic and Ancient art), and the evolving feminist response to the status quo – a response wherein her work was central. This beautifully-designed, oversized book, with copious illustrations, has two gatefolds that allow long, frieze-like works to be illustrated in their entirety; it is a fitting record of Spero’s ambitions and achievement.

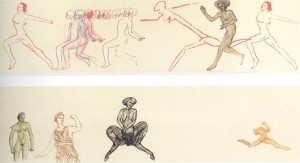

Nancy Spero (1926-2009) wanted nothing less than to re-insert women into history. Lyon discusses how her decision in 1966 to reject painting on canvas in favor of working on paper (in a variety of techniques, from gouache and ink to collage, stamping and handprinting) was a rebellion against the history of painting and the male power structure that supported it. Her decision in 1974 to represent women, and only women, was intended to recover the many female figures from history and myth that had dropped from view, as well as to posit women, not men, as the default mode for representing mankind.Lyone also describes the increasing debility of Spero’s arthritic hands, and its implications for her transition to printing to create her images.

Spero created work on a monumental scale in a format and technique entirely of her own making. Lyon’s carefully-researched text is a valuable guide to the ideas behind her many visual and verbal references (Spero’s texts were always citations), and to the evolution of her career in the context of increasing acceptance of work by women in major museums and galleries. This later is still not fully appreciated by younger artists. Her entire career was a heroic struggle to be heard. Spero’s work deserves the careful explication and generous reproductions of this volume, which is certainly the definitive text on an important, if under-acknowledged leader in activist art.

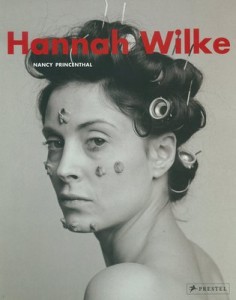

Nancy Princenthal Hannah Wilke (Munich: Prestel, 2010) ISBN 978-3-7913-3972-6

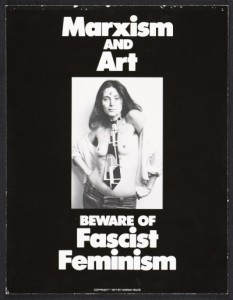

Princenthal has done an admirable and fascinating job of documenting the career of an artist whose work was often a lightening-rod for her viewers. She describes Wilke (1940-1993) as an artist who maintained the weakest of boundaries between her art and her life, and was often dismissed because of this, as well as because of her frequent use of her own nude and spectacularly beautiful body within her performances and photographic work.

Princenthal makes a persuasive case that, despite whatever subconscious motivations might have supported these decisions, they were artistic decisions. Wilke’s work was an exploration of beauty, of women’s bodies and the boundaries between public and private, and just as importantly, the reception of these topics within the art world. Wilke could not escape her beauty and the tendency of others to allow it to obscure her artistic production. Her art was intended to provoke its viewers. One of the strengths of this book is that Princenthal documents Wilke’s various and changing critical reception throughout her career.

Wilke’s earliest exhibited work was a series of ceramic pieces she called one-folds – sometimes shown singly, sometimes en mass on the floor. She produced these subtle, slightly abstracted but obviously vaginal forms before Judy Chicago created her lurid, vaginal plates as part of The Dinner Party (1974), and more than 25 years before Eve Ensler’s Vagina Dialogs – whose title was considered too explicit for many newspapers to publish in the late 1990s. Her art was in ongoing dialog with popular culture and with art history, most notably, her artistic dialog with Duchamp.

The reception of Wilke’s work is particularly interesting because of the about-face of many critics after viewing her final, posthumous work, Intra-Venus (1992), which documents the physical effects of her fatal cancer and its treatments. She was as unblinking in presenting her approaching death as she had been in her previous art, which was an ongoing challenge to everyone who assumed that a beautiful woman must be dumb. She was never dumb, in either meaning of the word. She was provocative, in-your-face, unguarded, funny, literate, bold, an artist whose important and very individual career still awaits inclusion in standard art histories. This book will certainly make that more likely.