Plus ca change …

Post by Andrea Kirsh

Mary Lucier

I was in Madrid last week for the opening of “First Generation; Art and the Moving Image (1963-1986), a large and very important exhibition which grew out of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia’s belated decision to begin to collect video art in 2005. The curator, Berta Sichel, decided to back up and look at the initial moment when video entered the art world. She produced the most international and comprehensive survey of early video art ever. Amazingly, the Reina Sofia had been able to acquire 85% of the work on display: 22 installations, 14 single-channel projections and over 80 single-channel works available at study monitors. The exhibition is on through April 2, 2007.

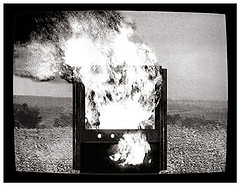

David Hall’s tv intervention shown on Scottish television.

The challenge of positioning this work in a museum is enormous. How can we understand the initial impact of pieces such as David Hall’s tv interventions in 1971, when viewers of Scottish tv had their evening’s viewing interrupted by a 2 minute and 58 second clip of a tv set in a bare landscape, missing its tube and on flames? The only narration was the single word,“interruption,” repeated slowly; or the 1977 live telecast from Documenta 6, showing Charlotte Moorman, a tiny tv set attached to each breast, gamely playing her cello as Nam June Paik slips various ridiculous objects (an empty radio cabinet, a gas mask with a camera lens in place of the mouth-piece) over her head? We are so used to being observed by closed-circuit security systems that the novelty of seeing ourselves in real time within Takahiko iimura,s “Face/Ings” (1977) has lost some of its surprise.

Carolee Schneeman

But the boldness of the women who used video, often in combination with performance, has not dimmed with time. Of the 14 international artists who came to the opening, I was most thrilled to be among several of these extraordinary women who did so much to change the art world: Dara Birnbaum, who created some of the earliest and most powerful critiques of mass entertainment; Mary Lucier, who has explored the interaction of eye and camera, inner and outer vision; VALIE EXPORT and Carolee Schneemann, both of whom forced the art world to acknowledge embodied, female consciousness, turning their audiences into their subjects. (More on VALIE EXPORT’s 2000 exhibition at the Paley Gallery, Moore College).

Hannah Wilke

My favorite story of the opening was of an elderly Spanish woman for whom the work was obviously new, for she expressed surprise that the artists were no longer young. Indeed, they haven’t all survived. The exhibition opened and closed with the seminal work of the late Wolf Vostell and Nam June Paik. The late Hannah Wilke’s “Suit Suite” grew out of a performance filmed for German tv at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Wilke, who had studied at Tyler School of Art, described it as the “ultimate film strip”: standing behind Duchamp’s “Large Glass,” she vamped as she removed her white, 3-piece, man-styled suit.

Hannah Wilke (l) and Anne d’Harnoncourt at the PMA

I had seen stills of Wilke, nude but for a fedora, playing chess in front of the Duchamp; but I hadn’t seen the footage of Anne d’Harnoncourt (now, Director of the PMA) with the artist who spat out her chewing-gum and formed one of her small, labially-shaped objects on the curator’s papers.

Dara Birnbaum

The challenge of retaining these pieces’ eternal youth (or at least of extending their lives) is a major concern for everyone involved with video. Most of the works in this exhibition had been converted to digital formats, but the only certainty of digital hardware, software and platforms is continual change. I met with Arianna Vanrell, a conservator at the museum who has been interviewing the artists to record their intentions. She’s participating in the International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art. INCCA’s North American committee is organizing a panel discussion on documentation for video artists as part of the upcoming College Art Association Annual Meeting in New York. It will be held on Friday, Feb. 16, 12:30-2:00 pm at MoMA, and will look at a case study of the work of Nam June Paik. It should be important for video artists as well as curators and historians interested in video.

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian living in Philadelphia. See her Philadelphia Introductions essays on emerging artists at inliquid.