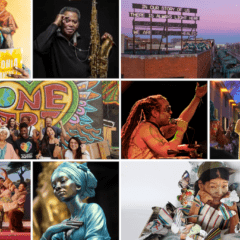

detail of Basketball Game/ Juego De Baloncesto, the only pop-culture reference in the exhibit–and then again, it goes somewhere else entirely

If I had three thumbs, I’d put them all up way high for Henry Bermudez’s solo exhibit at Projects Gallery. It’s a sort of antithesis to the pop-inspired work at Vernacular Spectacular Extravaganza (see post) –with only one small reference to a pop icon, the basketball–and a sort of antithesis to Tesoros, the rich, provocative exhibit of Latin American art up at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Dream in an October Night / Sueño en una Noche De Octubre

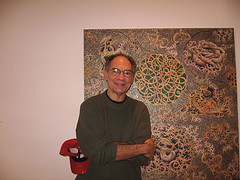

Yet Bermudez delivers work of great power, following a different drummer. This should should come as no surprise from an artist of Bermudez’ stature–he represented his native country, Venezuela, in the Venice Biennale in 1986, and his work hangs in a number of South American museums.

But Bermudez has been working relatively quietly in Philadelphia for a number of years now. His most public presence is in the Mural Arts program; he’s now working on his third solo mural. But he has also been creating arresting work revealing the magic that percolates through the world of the living.

Bermudez with one of his pieces

The day I stopped in at Projects, he happened to bound into the gallery, so I had a brief conversation with him about his use of dots. I had seen several traditional, ecclesiastical paintings in Peru that were covered with small dots, and here was Bermudez’ work, chock-a-block dotty. He said that Latin American art makes great use of dots, and that it dates back to the Maya and the Aztec cultures. I went looking through the Tesoros catalog after our conversation. I did find a couple of blue-and-white china pieces improbably covered with dots that transformed them from copies of Chinese bowls into things that seemed to shimmer with life.

the lacy Paisaje en quarto tiempo

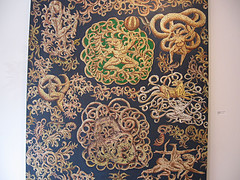

The pieces at Projects are painted paper collaged onto canvas. One series of paper cutouts is tacked directly to the wall. One wall has a group of masks. All these works have the same fundamental materials and methods–color and dots on cut paper.

The main colors are green and gold with dots of black, and in some, fields of red. Out of that minimal palette, glowing rope-y shapes snake and twine into balls and knots, suggesting mythic cosmologies. Sinuous lizards, jungle creatures and human forms coil and tangle and consume one another with restless energy under vibrating suns.

The results are swarming as they refer to a wide range of sources–from Medusa’s head to Aztec suns to atoms spinning; The work shudders with pre-Columbian gods, self-devouring snakes and with phantasmagoric creatures of the night. Wings and capes, vines and leaves all mix up in a forcefield at once romantic and threatening.

masks

Whereas Tesoros reflects how indigenous traditions infiltrated the cultural traditions of the conquerors, mostly the sense is of the conquest by the Catholics. What Bermudez offers is the utter subversion of the European tradition to an earlier one, a pan-universal one–the tumultuous vision of a magical world. Even when he goes directly to the Catholic traditions, he transforms them. His Saint Sebastian has a snake for a head; a filigree crucifix teems with Satanic wildlife. The masks with their beaky noses remind me of medieval Roman masks and ecclesiastical hocus pocus.

The first work I ever saw by Bermudez had a Medieval quality, a sort of unicorn tapestry peacefulness, with a figure floating in a red, patterned field. He has moved from that world, which was jungly, but decorous, to one of great turbulence. That seems appropriate in this time of war when our center doesn’t hold.

Bermudez’s primary sources may not be pop, but his work pops off the walls and challenges you to believe that there’s more all around us than the naked eye can see.

Don’t miss this show.

For more images (none of them come near to revealing the beauty of the work on the walls), here’s my flickr set and here are the gallery’s images of the work.