Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus brings a group of extraordinary paintings, drawings and prints by Rembrandt and his pupils to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA; organized by the PMA, the Louvre and the Detroit Institute of Arts, the exhibition is in Philadelphia through Oct. 30, 2011). It was conceived as a thematic exhibition exploring a question about Christian imagery, but the works can be viewed in many ways and will interest visitors for a wide range of reasons. Rembrandt’s work is rarely seen in Philadelphia, so let me begin with a short list of works from the exhibition, any one of which might justify a visit.

The Louvre has just cleaned The Supper at Emmaus, so that Rembrandt’s small gem of a painting of the sudden revelation of Christ’s holiness literally glows.

There’s a drawing that I’d long known but never seen: Rembrandt’s red chalk copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper. The Leonardo was famous and much copied as soon as it was completed. Rembrandt, who never traveled to Italy, clearly based it on the first engraved copy, of 1500, because he included the small dog at lower right, which was the engraver‘s addition. Rembrandt also made his own changes to the Leonardo, including putting a baldachin behind Christ. The exhibition includes seven other drawings by Rembrandt, each worth serious attention.

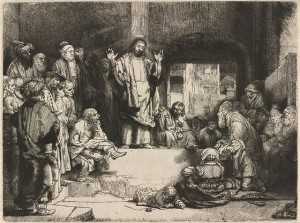

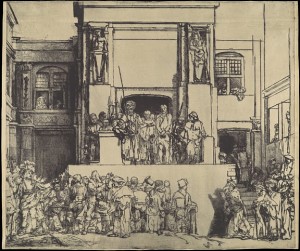

For anyone interested in printmaking, the exhibition is a treasure trove, with three particular knockouts: Christ Preaching, known as The Hundred Guilder Print (a splendid impression from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the print acquired its nickname because of the huge price it brought, as if Eakins’ Gross Clinic would forever be known as The 67 Million Dollar Painting); the Ecce Homo (further below); and the small Christ Preaching (La Petite Tombe) below. There are also multiple prints and related drawings on several subjects involving revelation: the Raising of Lazarus, Supper at Emmaus, and Christ in the House of Mary and Martha. The development of etching, as opposed to the earlier engraving process, opened the door to the painter/printmaker (engravers were usually copyists) and none was greater than Rembrandt. It would help to do some homework reading first, since The Hundred Guilder Print and Ecce Homo exist in multiple, and very different states, and the exhibition includes two states of the first, with no explanation to relate them. If you can find it, I recommend Rembrandt: Experimental Etcher (the catalog of a 1969 exhibition in Boston). The exhibition also includes a short and very useful video about the printmaking process.

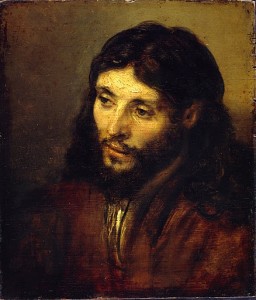

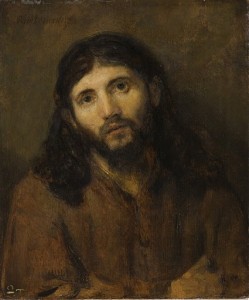

Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus was organized around a question: what did Jesus look like? Rembrandt seems to have raised the question around 1648, because it was then that he broke with the convention, well-established in Western Europe (and accepted by Rembrandt earlier, as the first painting in the exhibition demonstrates), of portraying Christ as fair haired with aquiline features – more or less a visual descendent of a Greek god. Rembrandt looked to his Jewish neighbors in Amsterdam for a more likely model. Portrayal of deities is highly conventionalized in all religions and cultures and never supposed to answer to each artist’s imagination. This was not the only time Rembrandt refused to accept conventional representations. His most prestigious commission, for the Amsterdam town hall, was rejected because he refused to create an ennobling figure of the early hero of the Dutch: Claudius Civilis.

A centerpiece of the exhibition is a group of small oils sketches which Rembrandt made of one model, who became the prototype of his dark-haired Christ (above and below). The PMA owns one, which had been in storage until cleaned in connection with the exhibition. The sketches must have been important to the artist, as they remained in his possession and were noted in his estate inventory. Several of them were acquired by other artists.

In Protestant Amsterdam, religious paintings would have been made for private collectors, as the churches had eliminated all representation (think of Sanraedam’s paintings of white-washed church interiors). Most of the paintings in this exhibition are small, and might well have been made on spec, rather than commissioned. The art market in the seventeenth-century Netherlands is the first that resembles our own, with artists producing work, then finding buyers in the newly-wealthy middle class; many artists specialized in one particular type and churned out multiple versions. The wall texts make no mention of what Rembrandt’s patrons would have thought of his new image of Christ; when I queried Lloyd De Witt, one of the exhibition’s curators (who was at the PMA when organizing the exhibition, and is now in Toronto), he thought that Rembrandt had loyal enough collectors that they would have accepted whatever he produced.

The exhibition can be seen as a study of Rembrandt and his pupils, as it contains a number of their works (some attributed to a specific painter, others not). There’s no question that Rembrandt taught, although there’s major disagreement among scholars as to how many students he had (estimates range from 21 to 99). One result of his pedagogy is evident in the exhibition: the spontaneous-looking draughtsmanship, with abbreviated outlines that look tossed off in a moment; this was clearly a learned effect, probably achieved with much, hard work. The pupils also employed Rembrandt’s diversity of paint handling, which included scratching into paint with the butt end of the brush. A number of their paintings are first rate; don’t be swayed by the name, or lack thereof, on the label (see below). As to Rembrandt’s innovation in the Christ figure, some pupils adopted his dark-haired Christ, clearly portrayed as a Jew; others reverted to the more common type.

The exhibition is filled with intimate works that demand close and careful viewing. If it’s as popular in Philadelphia as it was at the Louvre earlier this year, that will be difficult – but worth the effort. This is a rare opportunity and not to be missed.